Stigmatized for life: Marginalized victim groups

For people who were persecuted, deported, and imprisoned in concentration camps as “anti-social elements” or “career criminals,” official recognition as “victims of the National Socialist system of injustice” was long in coming. Not until February 2020 did the German Bundestag approve a motion to recognize these victims. Finally, after a lifetime of stigmatization, they are now included in remembrance and public commemoration.

The West German Federal Compensation Act of 1953 only granted compensation to people persecuted “on grounds of race, religion, or ideology”; the same principle applied in East Germany. This excluded many victim groups from social and political recognition as victims of persecution, including those labeled by the Nazis as “anti-social elements” or “career criminals,” who were obliged to wear black or green triangles during their time in the concentration camps.

The Nazis used the term “anti-social element” as a blanket term to justify the persecution of social outsiders, such as homeless people, prostitutes and their pimps, beggars, welfare recipients and, last but not least, “Gypsies and persons who roam about in the manner of Gypsies.”

Categorization of the prisoners

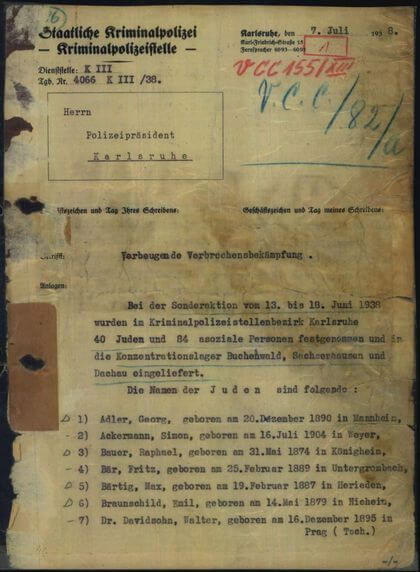

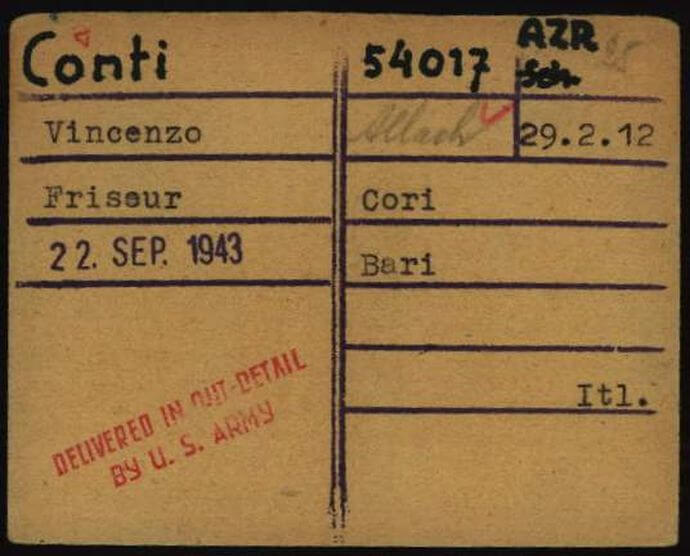

People who were arrested by the Kripo (police criminal investigation department) as “criminals” or “anti-social elements” on account of supposed or actual socially deviant behavior were categorized as “preventive detention” prisoners. Many imprisoned Sinti and Roma people were also categorized in this way by the Nazis. This sentence was passed on social outsiders (see the letter on the left concerning the “preventive” arrest of 124 people) as well as people who had just been released from prison, even though they had already served their time. The prisoner category AZR stands for “Arbeitszwang Reich” – “Reich compulsory work” and was often given to people who had been arrested as “anti-social elements.”

People who had a number of previous convictions for property offences were classified as “career criminals.” Even if they had long since served their prison sentences, they were taken into “preventive detention” and imprisoned in concentration camps as a means to remove them from the “people’s community.” There are also known instances of young men with no previous convictions being deported to concentration camps because local police officers “predicted” they would have a future criminal “career.”

A new initiative was launched only recently to recognize these people as victims of Nazi persecution at last. Most of the people assigned to these prisoner categories did not do anything themselves to inform the public about what had happened to them. Many kept silent about their time in concentration camps, or at the very least about the color of the triangles they were forced to wear. The reason for their reticence was a fear of stigmatization, coupled with the ongoing discrimination they often continued to face even after the end of the Nazi era.

Because of this discrimination, prisoners who had to wear green or black triangles left behind few personal testimonies, and there were no large-scale contemporary witness projects for them later, either. Estimates suggests that there were tens of thousands of these prisoners. The persecution they suffered can often only be pieced together from documents held in the Arolsen Archives, such as registration documents, or lists concerning transports, admissions and releases, medical treatment, labor details, or deaths in the concentration camps.

Thanks to the Central Name Index, which was designed to facilitate name-based searches, the documents in our archive can be used to reconstruct paths of persecution through the concentration camp system. This approach does not focus on individual places of detention, but on the prisoners and their movements between camps. This highlights the dynamic nature of Nazi persecution, the heterogeneity of experiences of persecution, but also the severity of the persecution suffered by these groups. A number of young people who were arrested in 1938 at the age of 16 for “gadding about” are a case in point. Some of them passed through seven or eight concentration camps in the following seven years, experiencing fresh horrors in each one. By the time they were liberated in 1945, they had spent a third of their lives in concentration camps, but no one looked after them afterwards.

In February 2020, the government majority accepted a motion put forward by the SPD and CDU/CSU for prisoners labeled “career criminals” and “anti-social elements” to be recognized as victims of Nazi tyranny and for public commemoration to focus more on the injustice done to them. However, this decision was largely symbolic – no new programs for compensation came about as a result. Perhaps the most important sentence in all the underlying motions and discussions was this one: “There was no justification for the imprisonment, torture, or murder of any person in a concentration camp.” This may seem obvious to us now, but it is the outcome of a decades-long public debate that gradually broadened society’s understanding of National Socialist injustices.