#StolenMemory

in Russia

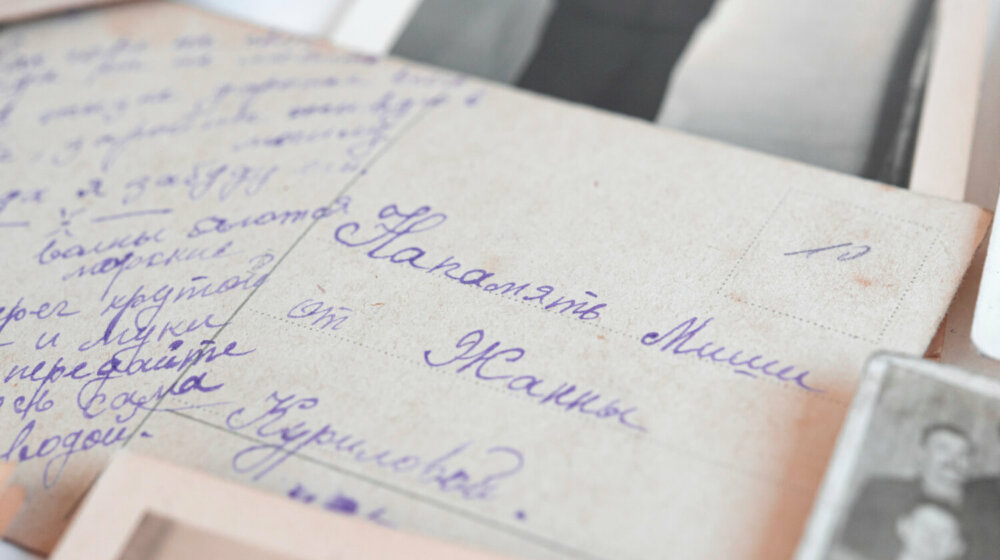

Following exhibitions in countries like Spain and Poland, #StolenMemory can now be seen in Russia. Two and a half million Soviet women and men were deported by the German occupying forces to perform forced labor. Many of them were sent to concentration camps, where they had to hand over all their personal belongings. The Arolsen Archives still have some of these items in their holdings, and they are looking for the families of the objects’ owners so that they can return the jewelry, photos, and watches to them.

In 1943, as the war became more and more desperate, the German economy’s need for labor began to grow. Young men and women in particular were carted off and put to work as forced laborers. A total of 2.5 million people suffered this fate. Even very slight infractions of the rules ended in concentration camp imprisonment for many forced laborers. To meet the Nazi regime’s demand for slave labor in the armaments industry, the SS also deported tens of thousands of people from all over Europe to the German Reich.

Many of them were women and girls, who had to do work that was just as hard and just as dangerous as that done by male prisoners. The camps were located near production sites that were important to the war effort, but their status as sub-camps meant that they were subordinate to the large concentration camps, which is where the personal effects were kept as well. This is why many of the objects could not be returned directly to their owners when the war ended.

Throwing a spotlight on the victims

The Arolsen Archives are putting on their very first exhibition in Russia in partnership with MEMORIAL, a human rights organization based in Moscow. The organization is committed to a critical examination of history and to supporting the families of former forced laborers in Russia.

A successful search

The Nazis took away Nelli Dmitrijewna Matwejewa’s jewelry when they imprisoned her in the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp on April 4, 1944. Nelli was only 19 years old and came from Kiev. She had to perform forced labor for a subsidiary of Siemens in the Zwodau / Svatava sub-camp in what is now the Czech Republic. At the end of February 1945, the SS transferred Nelli to the Beendorf sub-camp. She survived the evacuation of the camp and the death march towards Hamburg. Later she returned to the Soviet Union and married officer Alexandr Grigorjewitsch Pawlow. The two enjoyed a happy marriage and had two daughters, Ljudmilla and Tatjana. Nelli Dmitrijewna Pawlowa died in 2012 at the age of 87.

Tatiana Alexandrovna Rotanova was very happy when she held her mother’s bright red jewelry in his hands in the spring of 2019. With the help of the Russian Red Cross, the Arolsen Archives were able to find her in Moscow.

Around 2500 objects are still waiting

#StolenMemory was launched in 2016, and since then, we have been trying to trace the relatives of victims of Nazi persecution with the help of volunteers. Searching for the families is so very important because the persecutees’ personal effects are only stored in the archive, they do not belong there. In Russia, the Russian Red Cross is particularly helpful when we search for victims’ families. However, #StolenMemory is not just about showing the personal effects of the victims of Nazism in exhibitions and searching for their relatives – we also provide educational materials and videos that tell the stories of people like Helena and István; films based on their life stories are now available with Russian subtitles.

Helena Poterska was 16 when the Gestapo arrested her. But the earrings that the Nazis took from Helena when they arrested her found their way back to her daughters 77 years later. A memoir of the lost youth of the courageous Helena Poterska.

https://vimeo.com/444889902/59ced56ba8

István was Jewish and was arrested by the Nazis in 1944. 22 years after his death, the Roksa family received a message from the past. An envelope. Inside is an old fountain pen that István’s grandson Ravid keeps as a memory of his grandfather.

https://vimeo.com/427378718/859b452f66