"Now it’s our duty to make sure we don’t forget."

“Local Remembrance” – The Arolsen Archives launched this campaign to increase the visibility of small memorial sites and initiatives and to give them a voice to promote the valuable and important work they do. In this interview, Patrick Brion from the Walpersberg Memorial Association “Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Walpersberg e.V.” in Kahla (Thuringia) is talking to us about the work of the memorial site and the significance of the campaign.

Hello Patrick! Thank you for taking the time to talk to us about the “Local Remembrance” initiative. You’re a member of the Walpersberg Memorial Association “Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Walpersberg e.V.” in Kahla, Thuringia. Can you tell us a little about the historical background of the memorial?

When you think of memorials in Thuringia, the first ones that come to mind are probably Buchenwald and Mittelbau Dora. But the former underground armaments works near Kahla known as the “REIMAHG” ranks almost as highly in terms of importance.

The “REIMAHG” armaments works was a project that came under the sole responsibility of Fritz Sauckel, who was Gauleiter of Thuringia at the time. As the General Plenipotentiary for Labor Deployment in the German Reich, it was up to him to decide how many forced laborers were deported to Kahla. They were brought in from the occupied territories, but also from the immediate vicinity, where they were already working as forced laborers. But even then, he didn’t have enough to meet the demand, so he had systematic checks made on many companies and businesses in order to obtain more workers for his project. He addressed a blunt request to all production plants: “we need more people, send them over.” All in all, the workforce swelled to about 12,500 people: men, women, and children, who were all put to work as forced labors here.

Can you tell us a little about the work your association does too?

With pleasure. I first began to do research the “REIMAHG” works in 1993. A small amount of literature on the subject already existed at the time, and at the start, I wondered whether I would find out anything new that wasn’t known already! However, it didn’t take long before I had to change my mind. Many aspects of the history of this facility hadn’t been properly examined, had been misrepresented, or misinterpreted, or left unquestioned, archives hadn’t been consulted, and contemporary witnesses hadn’t been interviewed. Today, I can say that the research and the investigations that we have carried out all over the world have probably created one of the largest archival collections on this topic.

How did the archive/collection grow so large?

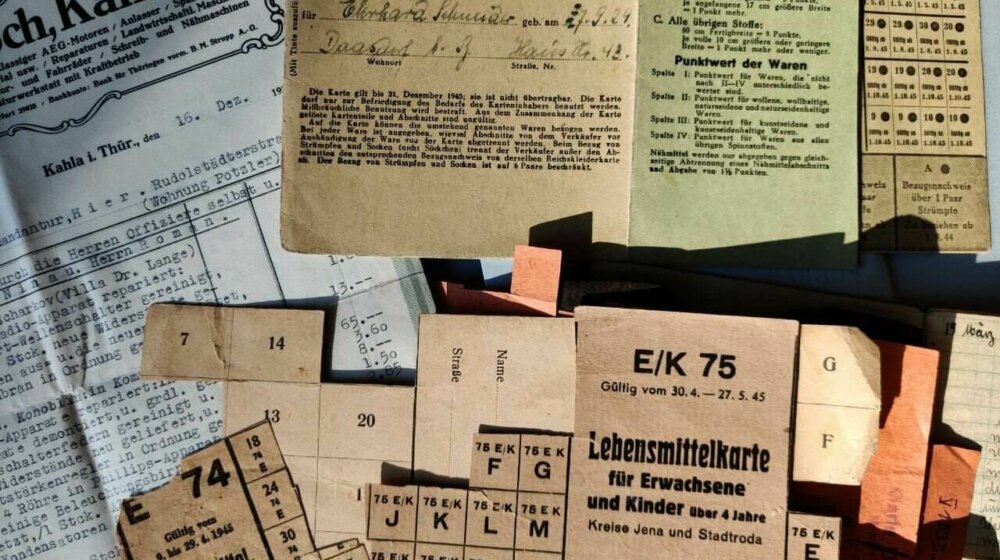

The gradual accumulation of archival material can be seen as a never-ending spiral. You start off at regional level by searching for documents and conducting interviews with contemporary witnesses. Then there comes a point when you move on to the State Archives, and from there you go on to the Federal Archives. And when you’ve got that far, you could say: “Alright, we’ve done everything now, that’s enough.” But that’s not what happened. In fact, this is the point at which our research became broader and deeper, because the forced laborers were deported from over 13 different countries, and that meant we really had to look into the archives of the individual countries too.

The Arolsen Archives are an enormous help to us here, of course – they are an incredible treasure trove of information. Thanks to our cooperation with the Arolsen Archives, we have been able to record or verify 8,000 names on the basis of documents from a number of archives and can now confirm that these people were employed here in this armaments factory. We were able to use this information to reconstruct and trace people’s entire life stories. Where did these people come from? What did they do here? Did they have any family here? Did they die here? Did they fall ill? Behind every document, there is a personal fate, a story. This often makes the research a very emotional and very deeply human experience.

Had you had any contact with the Arolsen Archives before? If so, in what context?

I’ll have to go back a bit to tell you about that. I was stationed in Arolsen between 1981 and 1990, in the Große Allee, the Arolsen Archives are in the same street. There were 600 of us, and none of us knew what was in the building just 500 meters up the road. That was during the period when the archive was pretty much hermetically sealed. It seemed to me that it was always surrounded by a great air of mystery, and I am extremely pleased that there have been so many positive developments over the past few years. The value of an archive has two aspects: What is in the archive and, in a sense more importantly, are the contents of the archive accessible?

I think the Arolsen Archives have understood the importance of both these aspects. Accessibility makes it possible to enter into dialog with many other places of remembrance, initiatives, and associations. This especially important for collective remembrance. And collective remembrance has an important role to play in ensuring that the past is not forgotten.

This energy and this sprit of constructive cooperation have now opened up a wealth of opportunities, and many new discoveries have resulted from the research they have inspired. Here’s an example. A few years ago, we discovered over a thousand ADREMA plates. These are small metal plates that are used in an administrative system for registering people, and the plates we found had been used to register some of the “REIMAHG” workforce, i.e. foreign and forced laborers, and German workers too; each person had a plate containing various pieces of personal information. It would have been nice if we could have found all 12,500 plates, of course. But thanks to the holdings of the Arolsen Archives, we were able to find almost 5,000 more names. So that made the list almost five times as long as it had been before – it’s an external file, and it tells us when the people arrived, which camp they were in, which company they worked for, and from when until when. This information made it possible for us to get in touch with other archives, such as the Red Cross in Moscow.

“My greatest hope would be that by working with the Arolsen Archives we can become a kind of hub where all those involved can come together and cooperate. Together we can piece together a more complete picture of our history and this will make remembrance more comprehensive too.”

Patrick Brion, Förderverein „Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Walpersberg“ e.V.

What motivated you to participate in the “Local Remembrance” initiative, where do you see added value, especially for the remembrance work that small memorial sites are involved in?

I think you have to look at the situation we have today. Some memorials receive enormous amounts of government funding, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with that. However, the unfortunate thing is that it doesn’t reflect the full range of places of remembrance and memorial sites. I think there were forced laborers in every town in Germany, in every town in the former Third Reich. This whole issue is very important for an understanding of history, and we need to add this aspect to the overall picture, we need to integrate this knowledge so that we can understand the complexity of the whole and give smaller places of remembrance more visibility at the same time.

My greatest hope would be that by working with the Arolsen Archives we can become a kind of hub where all those involved can come together and cooperate. The online seminars are a good way of doing this at the moment, and I hope that at some point we will also be able to meet and exchange views in person to give academics, memorials, places of remembrance, chroniclers, and people who are simply interested in history the opportunity to come together and see what kind of problems they have and how they can help each other. Together we can piece together a more complete picture of our history and this will make remembrance more comprehensive too.

As I always say when I’m giving a talk: Imagine a deciduous tree which has so many leaves that it’s impossible to count them. Stormy winds have scattered the leaves all over the world, and a similar thing has happened to all the information on the people who were victims of Nazi crimes. I’ve travelled to Moscow, England, America, Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, and Holland. Let’s say I manage to find five people as a result of the research I did there. Well, I’m happy with that. As far as I’m concerned, that’s a great success. Because those five people are five people we won’t ever forget.

What can people do to help you?

We’re very grateful for any kind of support, of course, including support of a financial nature. Obtaining funding is an especially slow process because funding always means a lot of bureaucracy and a lot of hard work, and that’s difficult, especially when you only have limited resources at your disposal. For me, the most important thing is for us help as many people as possible, so that as many people as possible can get information from us.

What does remembrance mean to you?

Remembrance has always been very, very important to me. I come from a professional background, and the army and remembrance can almost be said to go hand in hand. I was always confronted with it, have always been committed to it. The people who were alive then have passed information on to us today. And so we’ve become their ambassadors, their memories. We’ve taken on this commitment. We’ve listened to them. We’ve remembered. We’ve written it down. It has been preserved, in whatever form. Now it’s our duty to make sure we don’t forget. And that’s an incredibly important task.

Thank you for your time, Patrick!