Nazi persecution of queer people

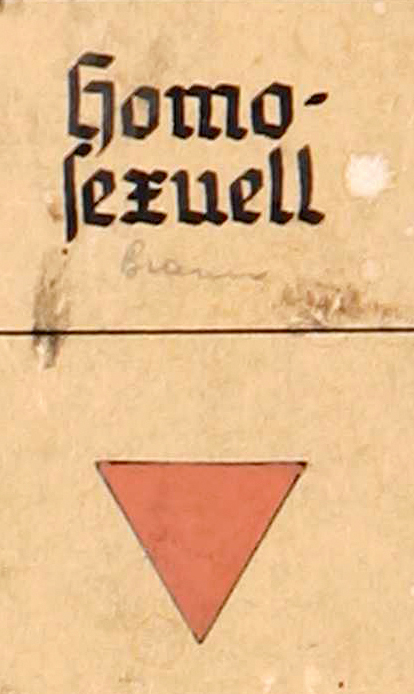

Prisoner categories are categories that the perpetrators defined in connection with persecution. These labels embody Nazi ideology and do not necessarily reflect either the identities of the people concerned or real events. Within the concentration camp system, different colored triangles were used for the different prisoner categories. Prisoners often had to wear a triangular patch in the appropriate color on their clothes. This made them immediately recognizable as members of a particular prisoner group.

Which prisoner categories were connected with the persecution of queer people by the Nazis? There is no clear-cut or conclusive answer to this question. The purpose of this article is to provide a brief overview of the relevant prisoner categories and to highlight problems that may arise when attention is focused on these categories. It should be noted at the outset that an analysis of Nazi persecution that does not transcend the boundaries of individual prisoner categories runs the risk of blinding us to the interconnections that can exist between different persecution contexts and may lead us to equate the identities of the people concerned with the categories they were assigned to.

The term “queer” only emerged as a (self-) designation for sexual and gender identities that fall outside the heterosexual norm or gender binary a few decades ago. When we speak of “queer” people in retrospect, we do so knowing that the people concerned did not refer to themselves as “queer.” This article by Julia Noah Munier (in German) deals with this topic in greater detail.

How was §175 used by the Nazis?

(Allegedly) homosexual men were criminalized on the basis of §175 of the German Criminal Code, which had been introduced during the German Empire already and was revised by the National Socialists in the 1930s, making it much harsher.

During the Nazi regime, about 53,000 men were convicted under §175 by German courts. Many of those who were imprisoned in concentration camps – researchers estimate that between 6,000 and 10,000 men belonged to this group – were made to wear a pink triangle. “Pink triangles” are also often found on the documents about the prisoners that the SS created in the concentration camps and that are now stored in the Arolsen Archives. This triangle frequently appears in combination with the words “homo.” or “§175.”

Men who were repeatedly convicted for “homosexuality” could also be detained in concentration camps as so-called “career criminals,” which meant they had to wear a green triangle. Under §175a, men could also be punished for committing sexual acts with (male) children or adolescents or with young men (under 21). They too were assigned to the categories “homosexual” and “career criminal” in concentration camps.

Not all of the people who were persecuted by the National Socialists as “male homosexuals” self-identified as homosexual or actually engaged in same-sex sexual relationships. Conversely, there were also men who self-identified as homosexual, but who were persecuted and deported to concentration camps by Nazi authorities for other reasons and were imprisoned as Jews or political opponents, for example.

In her recently published book “Menschen ohne Geschichte sind Staub. Homophobie und Holocaust” [People Without History Are Dust. Homophobia and the Holocaust], Anna Hájková turns her attention to the way different categories and risks overlapped in the context of Nazi persecution. She argues that the categories “Jewish” and “queer,” for example, have far too frequently been thought of as separate up until now: “It seemed that all persecuted homosexuals were gentiles, while the Jewish victims were always thought to be heterosexual” (Wallstein Verlag 2021)

What risks did lesbian women and queer people face?

The first in-depth studies on the topic of female homosexuality in the Nazi era began to be published in the 1990s and included works by Claudia Schoppmann. One reason why there are still so many unanswered questions connected with research on lesbian women in concentration camps and other places of detention is the fact that in Germany, these women were not persecuted on the basis of a criminal law provision. While women could be convicted of “homosexuality” in the Austrian part of Nazi Germany (cf. §129), this was not the case in the so-called Altreich (old Reich, a Nazi term for Germany with its pre-1938 borders), where §175 only applied to men. The extent to which lesbian women’s sexuality was the basis for their incarceration in concentration camps remains a contentious issue among researchers to this day.

In an article titled Lesbianism, Transvestitism, and the Nazi State: A Microhistory of a Gestapo Investigation, 1939–1943, Laurie Marhoefer uses the example of Ilse Totzke, born in Strasbourg in 1913, to discuss the special risk of being denounced by their neighbors that queer people and women who were thought to be lesbians were exposed to. Marhoefer shows that the women concerned were denounced on the basis of their sexual orientation or because their appearance did not conform to gender norms, and that this is how they came to the attention of the Gestapo. They could be sent to a concentration camp for a number of different reasons: if they had contact with Jews, were Jewish themselves, or belonged to the Sinti and Roma minorities, if they made statements that expressed any form of hostility to the state, or if they held communist views. This meant they were assigned to various different prisoner categories in concentration camps and had to wear different colored triangles on their prisoner clothing accordingly (e.g. red for “political prisoners,” black for “anti-social elements”).

An extensive bibliography, which also includes the work of numerous other researchers on this topic, can be found on the Website “Sexuality and Holocaust”.