Educational offerings and information services for Central Eastern Europe

Our “Outreach Eastern Europe” unit takes the Arolsen Archives and their services to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe because this region was particularly severely affected by Nazi persecution. We help victims’ families to clarify the fates of their relatives, and we work together with local partners to develop new educational offerings and information services.

We provide a point of contact and a range of services for people in countries like Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and the Russian Federation. This is important because the National Socialists acted with exceptional brutality in this region and persecuted, imprisoned, and murdered huge numbers of people. The materials stored in our archives can help shed light on the fates of individual victims.

The Arolsen Archives welcome inquiries and support learning and research. We help the descendants of Nazi persecutees find out what happened to their relatives. But we also run programs aimed at the general public in Central and Eastern Europe. As part of the #StolenMemory campaign, for example, we recruit volunteers at local level to help search for the relatives of persecutees whose personal effects are held in the archive so that these mementoes can be returned to their families.

We have already held exhibitions promoting the #StolenMemory campaign in a number of Polish cities to raise awareness of the search for relatives and let people know how they can help. This picture was taken in Krakow.

We involve school students in returning mementoes to families within the #StolenMemory campaign, and we support teachers by developing teaching materials that are suitable for use in lessons or school projects. We are open to cooperation in this area and place great value on direct dialog and on learning from one another. We also actively seek contact with local and regional archives with a view to developing joint projects to digitize and index documents.

Clarifying fates is of vital importance for the descendants of the victims

Millions of families in Poland and in Russia still do not know what happened to their relatives. The Arolsen Archives help the descendants of Nazi victims to clarify their fates. The case of Julian Banaś is an example of the kind of work we do. The German occupying forces deported him from Poland to Germany to do forced labor. He never returned. No one knew what had happened to him until his granddaughter Źaneta Kargól-Ożyńska contacted us. In response to her inquiry, she received a large number of documents with information about the fate of Julian Banaś in her own language.

»We were overwhelmed by how quickly we received the information from the Arolsen Archives and by how much trouble everyone went to in order to answer our questions.«

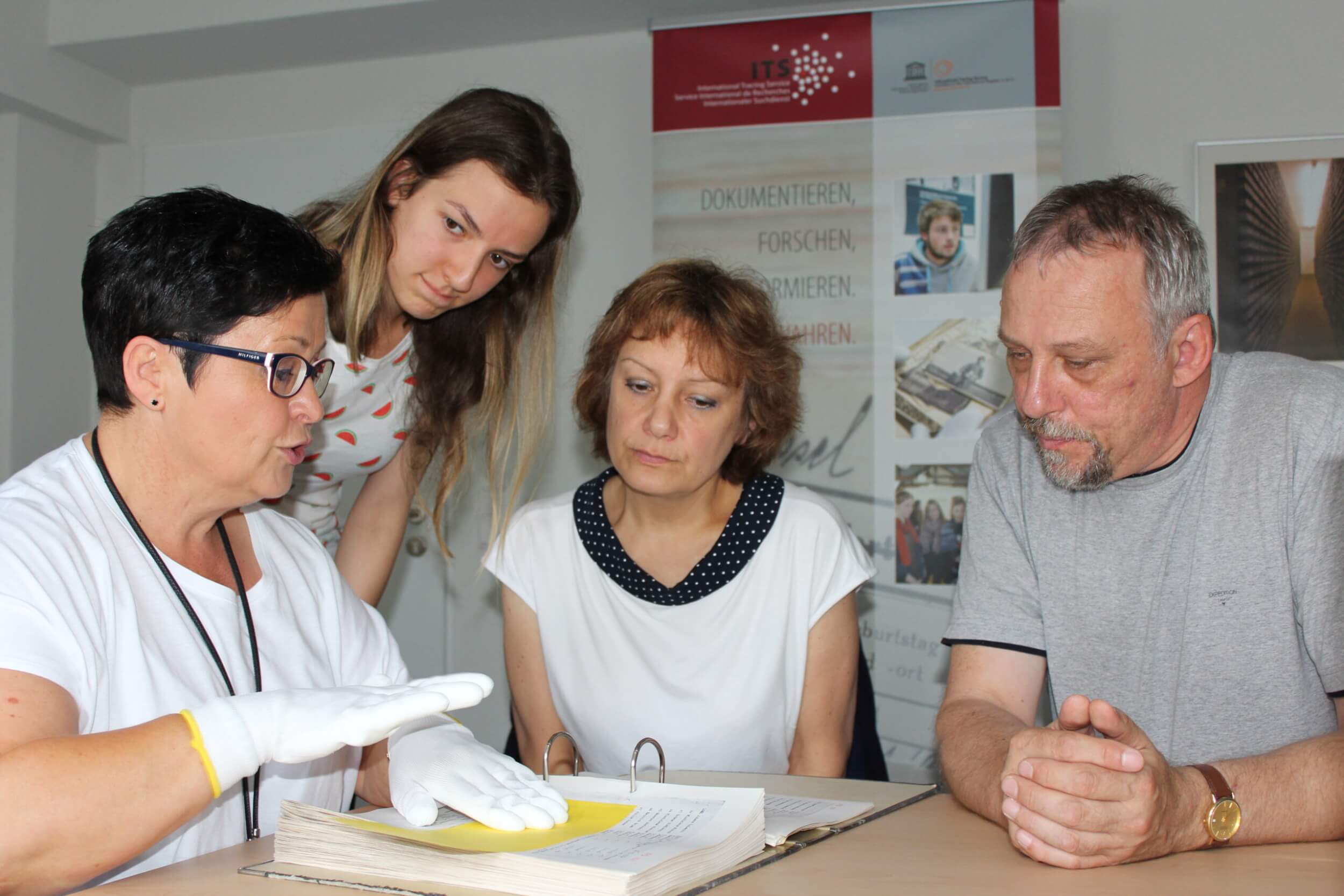

Źaneta Kargól-Ożyńska (2nd from right), granddaughter of Julian Banaś, a forced laborer from Poland

Thanks to the documents in our archives and some further research, Źaneta Kargól-Ożyńska managed to find out what had happened to her grandfather in Germany. She learned that he was executed by the Nazis and that a memorial initiative in the German town of Schwerte had already laid a “Stolperstein” (stumbling block) commemorative plaque in his memory. His granddaughter and her family were finally able to visit her grandfather’s grave and light a candle for him during a trip to Germany.

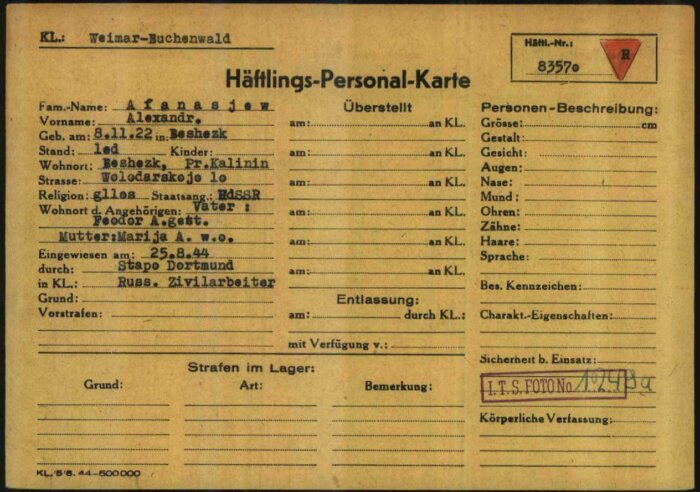

Certificates to document incarceration in a concentration camp

Alexandr Afanasjew, a Russian national, was made a prisoner of war by the Germans in 1944 and was sent to Buchenwald concentration camp. He spent decades searching for proof of his incarceration and finally found what he was looking for at the Arolsen Archives. His prisoner registration card (see below) is archived here, for example. He brought his daughter and his granddaughter with him when he came to Bad Arolsen to view the original documents. He was able to use them to help establish his eligibility for a compensation payment. Since 2015, Soviet prisoners of war have been able to receive a small sum of money from the Federal Republic of Germany in recognition of their suffering. Afanasjew used the money to finance the printing of his autobiography “Allein gegen Deutschland” (Alone against Germany).

Personal property returned to the Dobrowolska family

Janina Dobrowolska, a Polish national, fell into the hands of the German occupiers in 1944, along with her daughters Halina and Barbara. They were caught up in the systematic deportation of the entire civilian population that followed the Warsaw Uprising. The Nazis sent all three women to the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

This photo from the family’s private collection shows (from the left) Halina, Janina, and Barbara Dobrowolska a few years before their deportation. In 2019, we were able to return jewelry and watches belonging to the three women to Halina Dobrowolksa’s daughter – including this necklace with a Virgin Mary pendant that belonged to Barbara Dobrowolska.

The inquiry that Halina’s daughter had submitted to the Arolsen Archives also revealed that her aunt Barbara had been killed in a bombing raid shortly before liberation by the Allies. After evaluating documents on unknown foreign fatalities and unknown fatalities from concentration camps, we were able to locate her grave in Celle, Germany. The files also showed that Janina Dobrowolska survived imprisonment and continued to search for her daughter Barbara for the rest of her life.

Partnerships for the future of remembrance

We work together with important organizations in Central and Eastern Europe on cross-border remembrance and education work. Our partners include the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, the International Youth Meeting Center in Oświęcim/Auschwitz, and the Stutthof Museum. Since 2016, we have also been running a volunteer program with a focus on Eastern Europe in partnership with Action Reconciliation Service for Peace (ASF).

Millions of individual stories of persecution can be reconstructed with the aid of our comprehensive collection of documents on the fate of Nazi persecutees from Central and Eastern Europe. We act as a central hub for documentary holdings from a number of countries, and we help local archives with digitization and indexing. We have been receiving copies of important holdings from Ukraine, Belarus, and the Russian Federation for over 20 years.

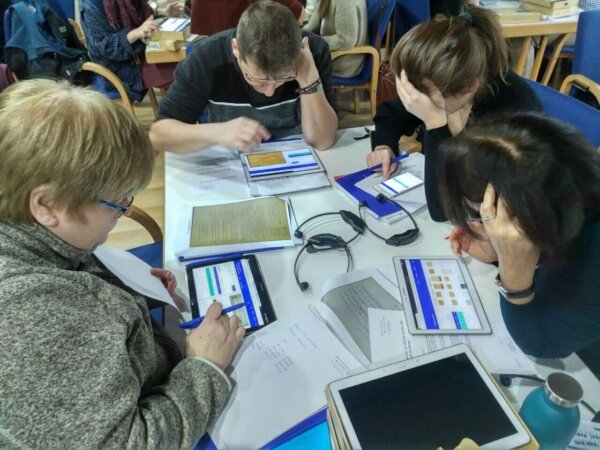

We offered our first Remote Access Workshop for the Central and Eastern European region in partnership with the Leonid Lewin History Workshop in Minsk. Participants were able to access the digital archive of the Arolsen Archives without having to travel to Bad Arolsen.

We cooperate with a large number of institutions in Central and Eastern Europe in order to expand our holdings. The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, and the human rights organization Memorial Moscow are just a few examples of the organizations we work with. The Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej) holds a full copy of our unique collection of indexed documents.

Would you like to launch a project with us? Anna Meier-Osiński is our Outreach Manager for the Central and Eastern Europe region. She is happy to answer all your questions about cooperation and partnerships.

Educational work at local level

Our collection of documents enables students to explore the history of persecution in their own region. Looking at individual fates is a very tangible way of approaching the topic. So we develop teaching materials that are suitable for teachers to use in the classroom. They are based on primary sources from our archive and are developed in partnership with local organizations. Archival pedagogy and research-based learning are central to our methods. We have already completed a pilot project with the Holocaust Center Moscow. The resulting materials are always published in English and in the national language of the partner institution, in this case Russian.

The International Youth Meeting Center in Oświęcim/Auschwitz (IJBS) is one of our most important partners in the education sector in Poland. We work together to offer workshops and seminars for educators from Poland and Germany promoting German-Polish educational work.

Educators attending a seminar at the IJBS are using the e-Guide and teaching materials produced by the Arolsen Archives.

In partnership with the IJBS, we have made the #StolenMemory campaign into an educational project in Poland. Young people attend seminars where they work closely with the biographies and documents of former concentration camp inmates whose personal belongings are stored at the Arolsen Archives. They conduct research into the fates of people from the region and search for traces that will enable them to find the families of the persecutees. With the support of Elżbieta Pasternak, an educational specialist at the IJBS, students Mateusz, Sabina, Maciej, Karolina, Kinga, and Zofia managed to return Stefan Baster’s wedding ring to his family in the summer of 2020.

»Meeting the niece of former concentration camp prisoner Stefan Baster was an emotional and unforgettable experience for us.«

Pupils from Oswiecim/Auschwitz

“There are many more questions waiting to be answered”

The Outreach Eastern Europe unit is headed by Anna Meier-Osiński, a cultural historian specializing in Central and Eastern Europe. She is an expert on remembrance in the German-Polish and Eastern European context and has considerable experience of working with the descendants of Nazi persecutees.

How important are the Arolsen Archives for relatives in Poland, Russia, Ukraine or Belarus?

Nowadays it’s very rare for us to receive inquiries from survivors themselves requesting documents about their persecution. That’s because they’re now very advanced in age. Today, most of the inquiries we receive come from the descendants of persecutees, i.e. their children, grandchildren, and often even their great-grandchildren. Especially in Eastern Europe and Russia, there are still millions of families who don’t know what happened to their relatives. Children and grandchildren are now looking for answers to questions their parents or grandparents never had a chance to ask. Each year, we receive over 15,000 inquiries from the later generations.

How extensive are the documentary holdings for Eastern Europe and Russia?

We have information on more than 17.5 million individuals. But we have received inquiries on around three million people. The numbers don’t match. So there are many more questions waiting to be answered. This still holds true when you take into account the fact that entire families were often murdered, which means there are no longer any relatives left who can search for them.

How do people react when they receive documents from the Arolsen Archives?

They’re often amazed at the wealth of information we can provide. Sometimes it’s possible to reconstruct paths of persecution in their entirety without any gaps. Often, though, it’s just certain stages of a person’s history. But even that’s important if you know very little. The descendants often learn to see their relatives in a whole new way. Sometimes families find the certainty they’ve been looking for for decades.

The current #StolenMemory campaign focuses on the “effects” that were confiscated by the Nazis, i.e. personal items that belonged to the prisoners. What is the significance of this campaign for Central and Eastern Europe?

The Arolsen Archives still hold personal effects belonging to around 900 Polish persecutees and over 350 persecutees from the states of the former Soviet Union, such as Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. #StolenMemory aims to draw attention to this special collection and help us find relatives in Poland, Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. But we also want to address the interested public and encourage them to participate. Anyone can join in the campaign to help search for traces of persecutees and return their personal belongings to their families.

What happens when personal effects are returned?

One of the partners we work with is the International Youth Meeting Center Oświęcim. Young people from Poland who take part in their projects research the fates of people from the region. Talking with family members has a central role to play when personal belongings are returned to families. Because it is only when we combine what we learn from talking to them with the information and mementoes in our archives and with the research carried out by the young people that we get a more complete picture.

What effect does it have on the families?

When we return personal effects to the families of victims of persecution, we usually find that they know practically nothing about the fate of their relatives. Often we can then give them important information, like where their relative is buried, for example. So it’s still all about clarifying fates, even after all this time. Making contact with families and documenting their memories also has an important role to play in the formation of collective memories.