A Paper Monument: The History of the Arolsen Archives

How can you find a missing person when millions of people are looking for their family members and friends and the events are receding ever further into the past? How did the archive come into being? Who used it; who had access to it? The permanent exhibition “A Paper Monument: The History of the Arolsen Archives” offers answers to these questions.

Between 1933 and 1945, millions of human beings were deported and murdered under Nazi rule. One of the largest archives on the crimes committed by the Nazis was created in Arolsen for the purpose of searching for missing persons and clarifying the fates of victims. It comprises more than 30 million documents, file cards and lists pertaining to Holocaust victims and concentration camp inmates, foreign forced laborers and survivors. Immediately after World War II, the victorious Allied powers created structures for tracing the victims of Nazi persecution and searching for documents that would help clarify fates.

»The Germans took my only child, a six-year-old girl, away from me in 1944, and all I know is that the child was supposedly in the Birkenau camp.«

Sarah Talvi, Athens, Nov. 16, 1948

It was from those efforts that the International Tracing Service (ITS) emerged in 1948. Originally planned as a temporary arrangement, it now became a permanent institution. Since 2019, it has been called the Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution.

The exhibition, which covers an area of approximately 160 square meters, is on view in Bad Arolsen in a former department store. This venue is temporary. Over the coming years, a modern archive building will be built, also providing space for the exhibition. The present venue is thus also a symbol of the transformations taking place in the Arolsen Archives. Some 245 exhibition objects offer insights into the eventful history of seven decades of searches for missing persons, the documentation of the Nazi crimes, and the changes that have taken place in how the institution deals with historical testimonies and the victims of those crimes. One highlight is the 26-meter-long installation of a section of the former Central Name Index.

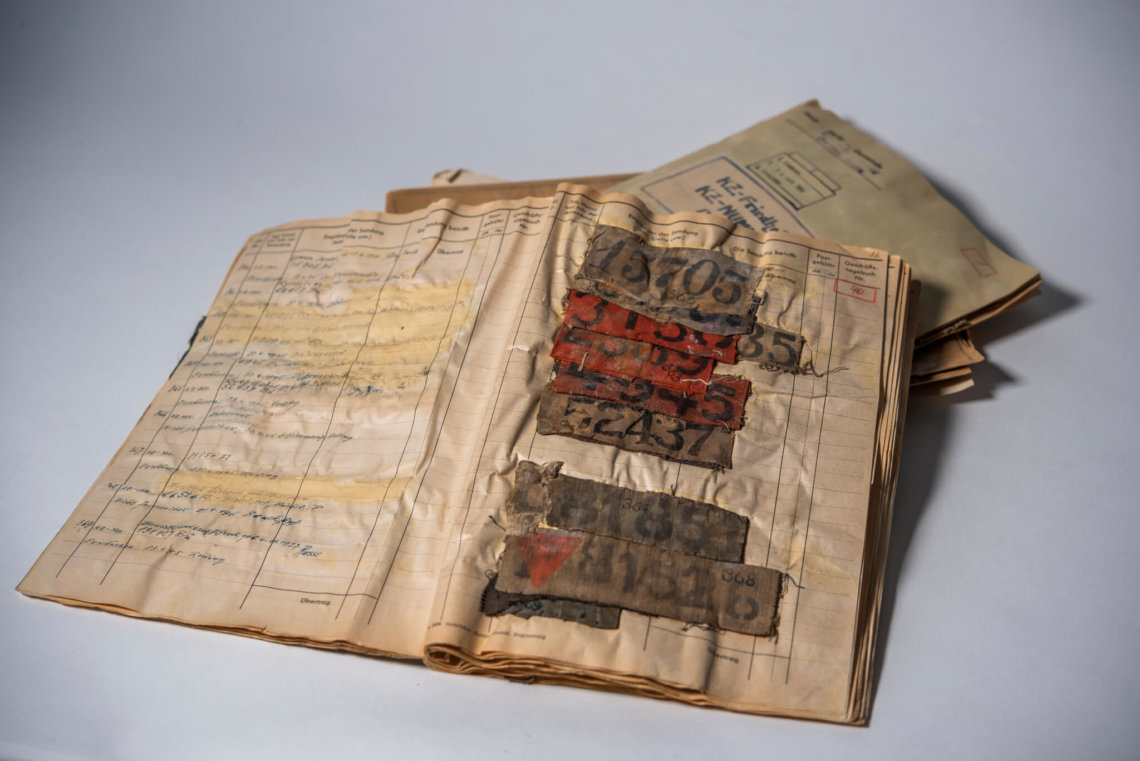

The portfolios document the exhumation of victims of the death marches using the prisoner numbers sewn onto their clothes

»My father is just one such victim among many millions, Jews and non-Jews alike, who shared his fate, including my maternal grandparents (…) They have no marked graves and no memorials other than the files housed here in Bad Arolsen.«

Thomas Buergenthal, 2012

FAQ

The exhibition is on view in a former department store on Schlossstrasse 10 in Bad Arolsen.

The exhibition is open to the public during the opening hours given above. There is no need to register in advance. Please contact us if you would like to arrange a private guided tour for a group. Alternatively, groups are welcome to join one of our regular public tours.

You can find more information about our opening hours here.

No. Visiting the exhibition as well as taking part in a guided tour is free of charge.