Clarifying

fates

Family members, scholars, journalists, hobby researchers, sometimes even the survivors themselves: Every year, thousands of people from all over the world contact the Arolsen Archives to learn more about the fates of victims of Nazi persecution. Our most important tasks after the war were search work and the clarification of fates, and these are still our foremost tasks today. The requirements for this work are empathy, interest for history, command of foreign languages and staying power.

We send the inquirers copies of the documents on file in the archive. But the processing of the inquiries also involves giving pointers on where else it might be worthwhile to ask for information and inviting family members to come to Bad Arolsen to study the documents in the original. Our employees then guide them through the fate of their relatives, explain the documents and provide contextual information about the system of Nazi persecution, forced labor or everyday life in the concentration camps. This service does not only apply to relatives: we also do research for hobby researchers, historians, journalists and anyone interested in Nazi persecution. Of course, everyone can do their own research on-site at the Arolsen Archives and will receive comprehensive advice and support from our employees.

Research on-site at the Arolsen Archives.

Paths of persecution

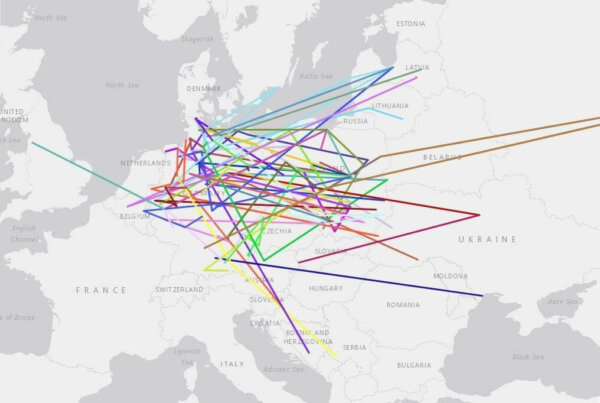

Many of the victims were persecuted for years, arrested multiple times, and deported to various locations. Nazi terror sometimes took these people all over Europe. The perpetrators kept meticulous records of the deportations, the committals to the concentration camps, and the illnesses and deaths suffered there. These records have not survived from all of the camps, but the Allies managed to seize large quantities of documents at the time of the liberation. The collection was systematically expanded to make as much information as possible available from a single place.

Criss-crossing all over Europe: the paths of surviving forced laborers and concentration camp inmates who emigrated to the United Kingdom from 1945 onward.

As a result, the Arolsen Archives staff are able to provide information in somewhat over 50 percent of the cases. Sometimes they only have fragmentary information to offer; other times it proves possible to reconstruct a victim’s persecution history in its entirety, from initial arrest to death or liberation. In many cases, however, the names of the victims have not come down to us. That is because, in the extermination camps and in the context of the mass shootings in Eastern Europe, the murderers no longer went to the trouble of recording the people’s names.

Tracing Individual Fates

-

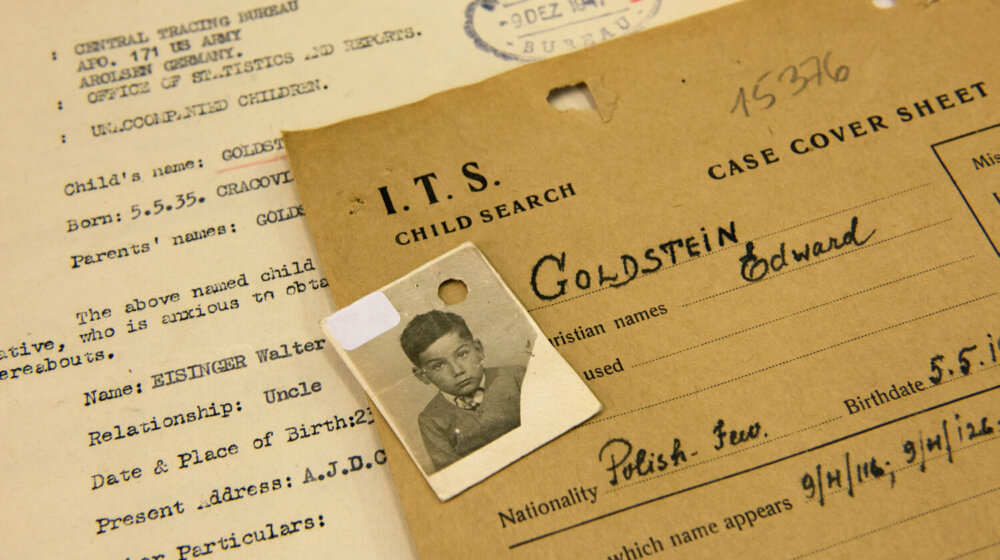

Returning “effects”: In the holdings of the Arolsen Archives, there are still hundreds of personal items that belonged to concentration camp inmates. Our mission is to search for families—or the survivors themselves—so we can return these so-called effects to their rightful owners.

Returning “effects”: In the holdings of the Arolsen Archives, there are still hundreds of personal items that belonged to concentration camp inmates. Our mission is to search for families—or the survivors themselves—so we can return these so-called effects to their rightful owners. -

Uniting families: Tens of thousands of families were separated in the context of Nazi persecution. Many people are still looking for their relatives. We help them in their search.

Uniting families: Tens of thousands of families were separated in the context of Nazi persecution. Many people are still looking for their relatives. We help them in their search. -

Finding graves: It’s important for families to know where their relatives are buried so that they can visit their graves. The Arolsen Archives have thousands of documents containing information about the places of death and gravesites of victims of Nazi persecution.

Finding graves: It’s important for families to know where their relatives are buried so that they can visit their graves. The Arolsen Archives have thousands of documents containing information about the places of death and gravesites of victims of Nazi persecution.

“It’s not work, it’s a mission.”

Malgorzata Przybyla has been working for the Arolsen Archives since 1992. She has worked on hundreds of inquiries, primarily from Poland. She sees her work as a matter of the heart that presents her with ever new challenges: The questions younger generations ask about Nazi persecution are entirely different from those of their grandparents. Digitalization has changed a lot. And every search brings to light individual fates that in turn testify to the impact of National Socialism on people throughout Europe.

Mrs. Przybyla, how has your work changed over the past years?

Our work has become faster and more direct. Today I can oversee an inquiry from beginning to end. As a result, the relationships to the inquirers are much more personal. We used to have four or five of us working on one case. Digital technology simplifies our work tremendously, also the digitization of other archives. Today it’s very easy for me to find out whether someone is already being searched for in a different online archive.

What qualifications does your work require?

Command of the language and familiarity with the respective country are extremely important. I work almost exclusively on inquiries from Poland. The people there greatly appreciate it when a “countrywoman” communicates and empathizes with them in their own language. Poland was hit especially hard by Nazi persecution. There’s a persecution story in almost every family. So empathy plays a big role—and that’s something that takes time.

Was your own family affected by persecution?

My grandfather perished in a concentration camp, so I never knew him. My family attached a lot of importance to honoring this part of our history. And to learning about it. Nearly all of my relatives are hobby historians. A lot of knowledge about World War II and a strong interest in the history of Nazi persecution: those are also important prerequisites for my work here.

Have you learned a lot about that history here at the Arolsen Archives?

Yes, especially when I started out. I immigrated to Germany from Poland at the age of 27 as the wife of a so-called late ethnic German repatriate. However much we talked about it in the family, my school education was based on the attitude that all Germans were perpetrators. And only the Germans. The fact that, two weeks after the Nazi invasion, Poland was invaded again, now by Russia, was never mentioned in our history classes. Here in Germany, and especially at the Arolsen Archives, I’ve gotten to know many German opponents to, and victims of, the Nazis. That enables me to look at my country’s history from two perspectives. I also always try to convey that to people in Poland.

So part of your work is also to teach about history?

More and more. In the 1990s, when I started out here, it didn’t play much of a role. Back then, we had a lot of inquiries from survivors who needed proof of their imprisonment or deportation, for example. Naturally, we didn’t have to explain to them what a concentration camp was, how things were organized in the camps, what the inmate category “professional criminal” on a document means, etc. At worst, they knew all about these things from personal experience. Today, most of the inquiries come from the children, grandchildren, sometimes even the great-grandchildren.

What’s a typical inquiry from these younger generations?

Now the concern is with clarifying fates and researching one’s own family history: “In my family they say there was an uncle who was deported and never returned. I’d like to find out what happened to him.” A lot of Polish families these days are very interested in genealogy. Sometimes people want to learn more about grandpas and grandmas who they knew, but who never talked about what they had experienced. These grandchildren need a lot of additional information about the Nazi persecution system. They want in-depth explanations of the documents and information—preferably in Polish.

How do you go about searching?

My first stop is our Central Name Index, to find out whether we even have information about the person. That may lead me to further documents. There I can often find information such as the last place of residence or the names of the parents or siblings. Then, for example, I can look for family members with the help of the Red Cross. These days, my main task is to search for the relatives of former concentration camp inmates in cases where we still have personal belongings, such as watches or jewelry, in our archive. There are hundreds of Poles we still have to find so we can return these items to them.

Are there cases that have made a particularly strong impression on you, that you’ll always remember?

Many. For example the sad but beautiful story of a little boy. He was born in Austria in 1945. The Nazis put him on a transport to Poland with hundreds of other children. He was rescued en route by a Polish family. He grew up with them, but it was only after his Polish parents died that his oldest sister told him the story. Then he inquired with us. At around the same time, we had an inquiry from a couple from Belarus who had emigrated to Australia after the war. They had been forced laborers in Austria and had a son there. The Nazis took the boy away from them and two weeks later told them he had died. Those were his parents! We were able to reconstruct that with the aid of our documents. At the age of sixty, the son was reunited with his mother and met his siblings in Australia. Sadly, his father had already passed away.

Isn’t your work also often depressing?

I always say: it’s not work, it’s a mission. Our work has to do with one of the darkest hours in human history. It’s often ugly, it’s about many terrible and sad fates. But the inquiries we get are from people who want to know everything. They want clarification and they need support. The personal relationships that often come about, the trust people have, the gratitude—all those things make my work easy. There are stories I can’t stop thinking about—in those cases I even continue the research in my free time!

Three Women, Three Generations

After his liberation from the Dachau concentration camp, Mirjam’s grandfather Abraham emigrated to Israel without his wife and daughter. His German granddaughter wanted to find out more about him and asked the Arolsen Archives for help. Abraham’s fate, which took him through various concentration camps over the course of many years, proved to be well documented in our archive. An Israeli aid organization supported us in the search for other relatives and quickly found out that Abraham had had a son and another daughter in Israel. During a family reunion in Israel, Mirjam, her daughter, and her half-sister Yaffa talk about what it feels like to suddenly have a “new” family: