A flower for Benedek Sátori

One of around 7,000 forced laborers who were made to work in the Ohrdruf concentration camp near Gotha in 1944/45 was Benedek Sátori from Hungary. Over decades no one knew what had happened to him. That changed when his grandson Péter Füzi submitted a tracing inquiry to the Arolsen Archives.

Péter Füzi stops for a moment by the steep limestone cliffs in the Jonastal valley in Thuringia, his hands clasped behind his back, his deep-set eyes shielded by sunglasses. It is April 23, 2024, and Péter, a retired Hungarian mathematician, has a long journey behind him – in more sense than one.

Under a group of pine trees in the Jonastal valley, he and his wife have planted some purple wildflowers. They brought them all the way from their garden near Budapest to honor the memory of Péter’s Jewish grandfather, Benedek Sátori, who probably died here, in the Ohrdruf concentration camp near Gotha, at the beginning of 1945. It still cannot be said with absolute certainty exactly where and when he died.

Péter Füzi takes a photo of the flowers he planted in memory of his grandfather in the Jonastal valley. (Photo: Arolsen Archives)

Missing near the western border of Hungary

Benedek Sátori was born in Budapest in 1897, into a Jewish family of industrialists. Wounded while serving as a soldier in the First World War, he was honorably discharged with a medal for bravery. He got married in the 1920s and took a job as a secretary at the Royal Hungarian Automobile Club.

Benedek Sátori (left), his daughter Adél, 1935, (center) and Adél with Peter, 1958. (Photos: The Füzi family album)

When he was younger, he had become romantically involved with the family maid, and he fathered a daughter, Adél, whom he looked after until he died. Because of anti-Jewish legislation introduced in Hungary from 1938 on, he suspended efforts to adopt her and recognize her officially as his own daughter. Adel’s mother came from a Christian family, and his precaution helped Adél to avoid the Holocaust. For as long as he was able to do so, Benedek paid her living expenses and financed her vocational training so she could live near him in Budapest.

In November 1944, Benedek Sátori was called up for labor service and sent to Hungary’s western border near Sopron. On a postcard posted in Balf near Sopron on December 7, 1944, he wrote:

»Our days pass by in rather difficult circumstances. Sometimes we would rather be dead than alive.«

Benedek Sátori

A gap in the family’s history

The message on the postcard was the last anyone heard from Benedek. Meanwhile, his daughter Adél had completed her training as a hairdresser. She spent the war years in hospitals and sanatoriums receiving treatment for a chronic lung disease. After the war she was convinced that her father had died near the western border. She told her 20-year-old son Péter as much when she showed him the postcard his grandfather had written. She held onto this belief until her own death in 2014, aged 89.

Only when Péter retired did he begin to delve deeper into his family history. When he contacted the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest to have his grandfather commemorated as a victim of Nazi persecution on their “Wall of Victims,” they advised him to submit an inquiry to the Arolsen Archives.

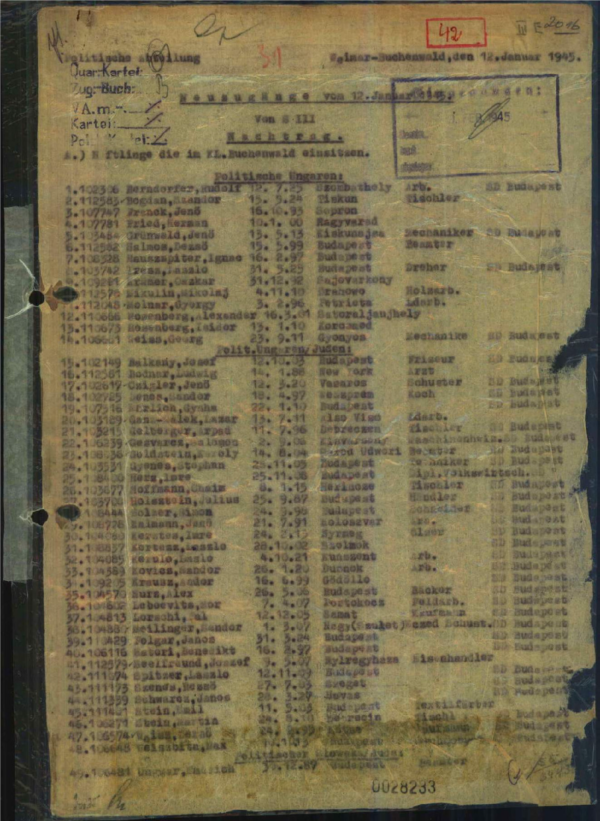

A brand new chapter – Traces in the archive

Documents from the Arolsen Archives suggest the following course of events: Benedek Sátori was deported from the Balf camp in occupied Hungary to Thuringia in December 1944, presumably first to Buchenwald. He spent Christmas in the Ohrdruf sub-camp. The last documentary evidence of his presence there dates back to mid-January 1945. After the end of the war, in December 1945, a list of the Hungarians who died in Buchenwald concentration camp was drawn up. It includes his name, although he probably died in Ohrdruf. The Ohrdruf sub-camp was under the administration of Buchenwald at the beginning of 1945.

Ohrdruf concentration camp

The Ohrdruf concentration camp was set up as a sub-camp of Buchenwald in November 1944. Prisoners had to perform forced labor under inhumane conditions in the nearby Jonastal valley, where they had to dig at least 25 tunnels into the hillside. We now know that around 7,000 of the camp’s prisoners died. The complex was probably supposed to serve as alternative “Führer headquarters,” a final refuge for Hitler and the Reich government. It was never completed. The Ohrdruf concentration camp was the first of over 130 Buchenwald sub-camps to be liberated by the US Army in 1945.

Telling young people about the Holocaust

Finding out what happened to his grandfather is very important to Peter Füzi, and in April 2024, he traveled from Budapest to Ohrdruf to visit the former site of the concentration camp. He also spoke to pupils at a nearby secondary school in Ohrdruf. Himself a father with three daughters and two grandchildren, he is keen to talk to young people about his grandfather. He puts it like this:

»When we remember any single one of the victims, we remember all of them, the entire Holocaust.«

Peter Füzi

In his opinion, this is why it is important to continue to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust and to do so in a way that corresponds to the abilities and maturity of the audience.

From concentration camp to military training area

The site where the Ohrdruf concentration camp used to stand is now a military training area used by the German Armed Forces. It is open to the public by appointment. Only three small memorials, two memorial stones and a bell, commemorate the camp and its victims.

To take a virtual tour of the grounds, go to “Suspicious – A Landscape of Crime,” an educational resource on our “and today?” platform.

While he was visiting Ohrdruf, Péter Füzi gave an interview to Birthe Pater, Head of Education at the Arolsen Archives. He spoke to her at length about his family history; the video of their conversation is in English.