Forced Adoption: Anton found his family in Ukraine after 50 years

Every week, Anton Model calls his Ukrainian family in the war zone. In actual fact, he grew up as the son of a winegrower in idyllic Hagnau on Lake Constance and had no ties with Ukraine. When he learned by chance that he had been adopted, a year-long search for his Ukrainian birth mother began.

“I have many friends and supporters. Without them, I would never have managed to find my mother,” says Anton Model. His children and grandchildren are sitting around him. He never had any contact with his family in Ukraine until 1992.

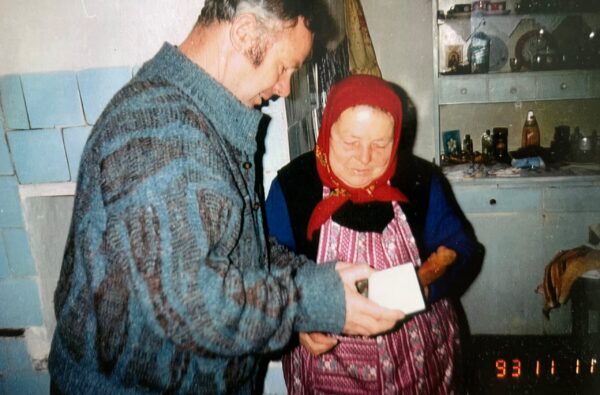

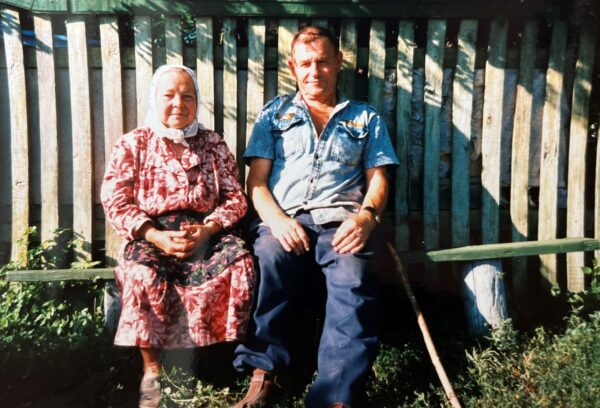

Anton Model and his birth mother (Photo: Private)

First traces of adoption

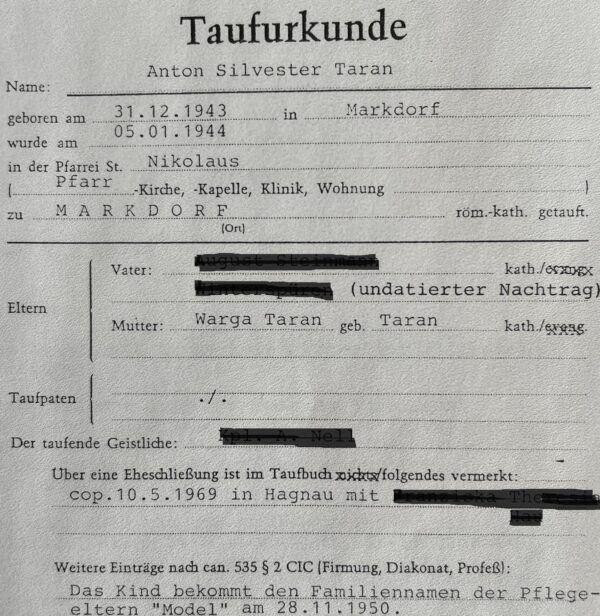

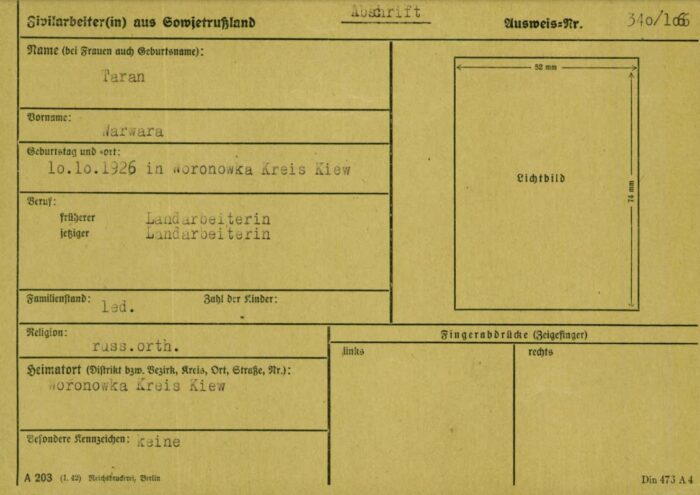

Anton Model was born in Markdorf on December 31, 1943. When he was twelve years old, he found a baptismal certificate and an adoption contract for “Anton Sylvester Taran” in his father’s bedside table. Information about his biological mother was recorded in the documents: “Warga Taran, born October 10, 1926, Ukrainian”. Anton placed the documents back and did not tell anyone about his find for a long time. He was in shock and did not know how to make contact with someone in Ukraine.

Anton Model’s baptism certificate

Did Anton’s mother survive World War II?

Knowing that he had a biological mother somewhere on the other side of the continent did not let Anton Model go. Why had the young Ukrainian woman been to Germany? Had she survived the war? Why had she put up her child for adoption?

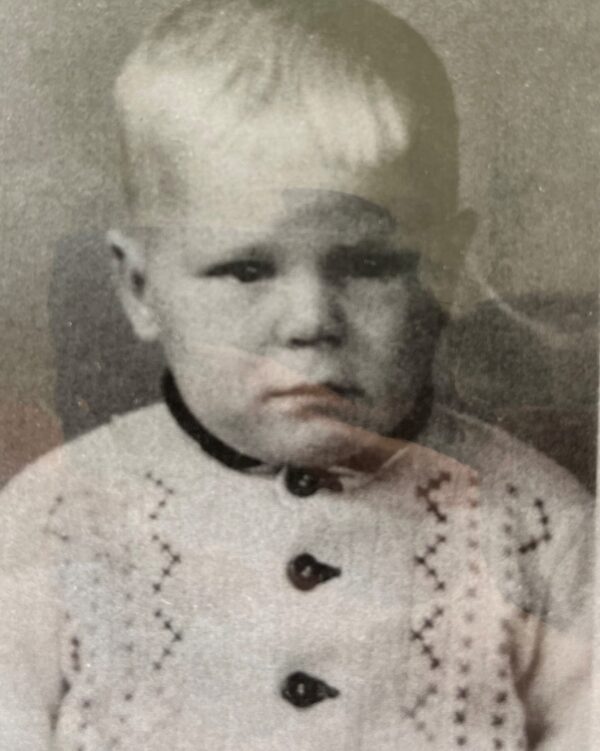

Anton Model as a child in Hagnau (Photo: Private)

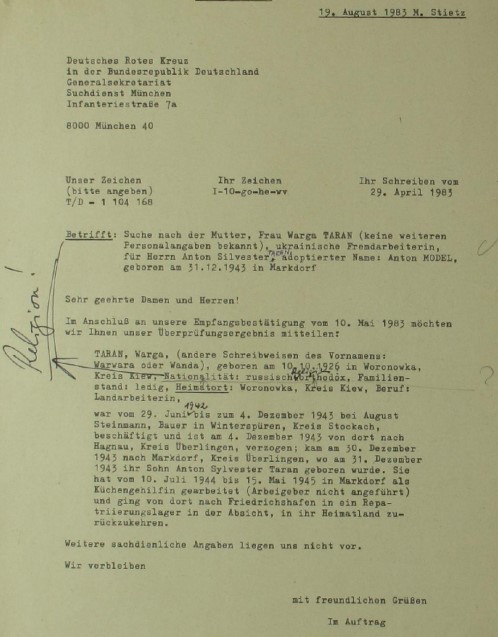

It was much later only, in the 1980s, when he began his search. By this time, he had already married, had children of his own, and taken over his father’s wine farm. “I really wanted to try everything I could to meet my mother. I went to all the archives, I wrote to all of them,” he recalls. The French authorities responsible for the occupation zone at the time when Anton was twelve and asked about documents relating to his mother told him that they had given all the records to the International Tracing Service, now Arolsen Archives. He made his first inquiry not until 1983, though, and found out about his mother’s last known address.

Documents about Warga Taran in the Arolsen Archives

The Arolsen Archives hold several documents relating to Warga Taran’s forced labor, the adoption of her son Anton Model, and Anton’s search for his mother. The so-called T/D file contains all inquiries received and answers given by the International Tracing Service concerning the Taran family since the end of the war.

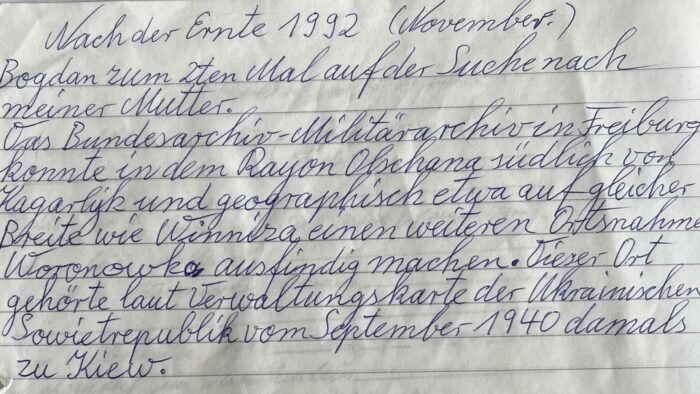

Seasonal worker found Warga in Ukraine

But even the address failed to further Anton’s search. In a Europe that was divided by the Cold War, a search in Ukraine was almost impossible. Anton then got help from one of the seasonal workers jobbing on his wine farm every summer. One summer, one of them, Bogdan, offered to visit the last known address of Anton Model’s mother in his home country. Back in Ukraine, Bogdan asked his way from village to village, looking everywhere for Warga Taran. And he finally found her.

Family reunion after 50 years

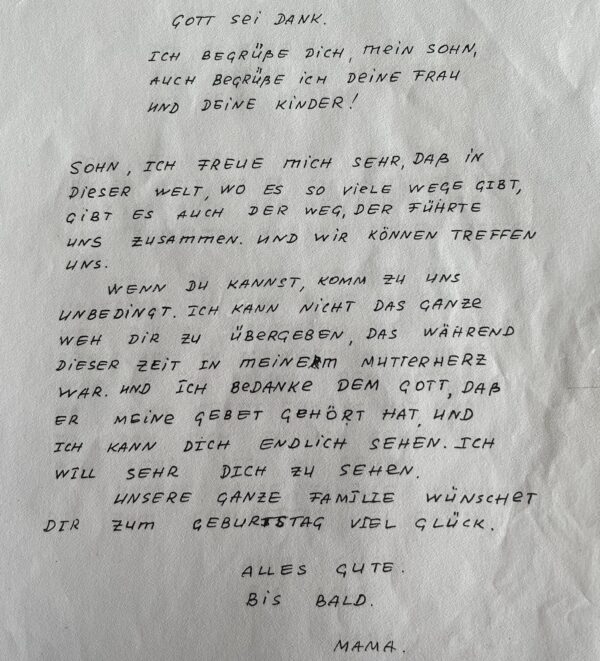

Son and mother were separated from each other for almost 50 years. With the help of his Ukrainian friend Bogdan, Anton was able to enter into letter communication with his mother in Ukraine in the 1990s. Bogdan translated all the letters, because Warga had “unlearned” German over the decades.

The Nazis deported Warga for forced labor

Over the years, Anton Model pieced together his mother’s fate. Then 16-year-old Warga Taran had been deported by the Nazis to Germany for forced labor. First she worked for religious sisters at Lake Constance, then on a farm.

“When it became known that she was pregnant, she was picked up by two Gestapo men, taken to the district court prison in Constance, and subjected to terrible interrogations. The Gestapo was desperate to find out who the father was. But she was steadfast and didn’t give him away.”

The Gestapo released Warga, and she worked as a domestic help for the mayor’s wife in Hagnau from then on. After the end of the war, she registered as a displaced person and returned to her Ukrainian homeland. But: she left Germany without Anton.

Warga Taran and her husband, 1993 in Ukraine (Photo: Private)

Anton with his adoptive parents, about 1955 (Photo: Private)

Family reunion after long years of search

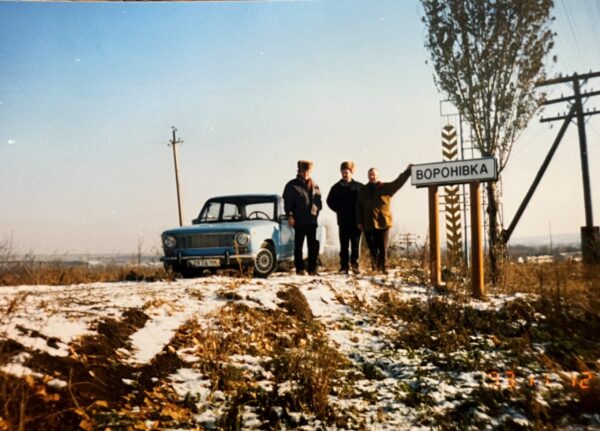

In 1993, the time had finally come. Anton’s friend Bogdan took him to Ukraine. In the freezing November cold, the two traveled to Warga. “I will never forget that day, it was overwhelming,” Anton recalls. Every time he talks about his encounter with his mother, tears come to his eyes. The first time he stood before his mother, she cried out, “My child, my child!” At that time Anton was already 50 years old.

After years of searching: Bogdan and Anton drive to Warga’s home village in 1993 (Photo: Private).

Anton’s second family in Ukraine

After the war, Warga had married a Ukrainian in her homeland and had three daughters with him. Growing old, she suffered in health from the consequences of the heavy forced labor. In 2004, Warga died at the age of 78.

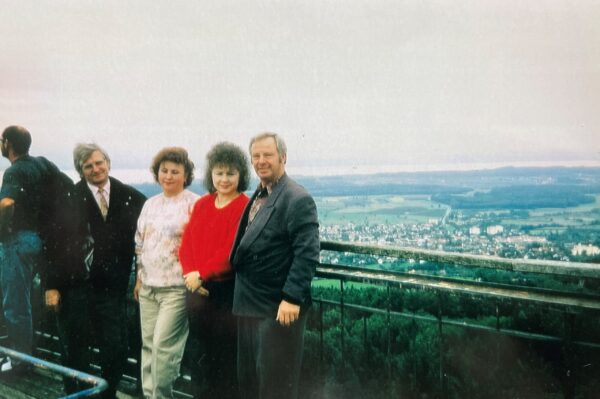

Does Anton still have contact with his half-sisters? “Haja, of course!” he affirms, “I call three times a week.” His half-sister Tanja speaks German, she is a teacher in Ukraine. Anton’s sisters visited him several times in Germany, and they maintain a close relationship to this day. “We invited Tanja here too, but the principal asked her to stay. He wants to start teaching on site again soon, despite the war.”

Two of Anton’s Ukrainian half-sisters visiting Germany (Anton on the right in the picture) (Photo: Private)

How can you help Ukrainians?

His sisters are not well, Anton says: “The worst thing is the sirens”. The phone calls with them are difficult for him. “You feel really bad,” he explains. He feels powerless, unable to do more than offer help and listen. “Ukrainians have a will to survive, it’s madness.”

Deportation of Ukrainian children

Anton is particularly shaken by the reports of Ukrainian children abducted by Russia: “That makes me think of my fate, I had a similar situation. I hope the children can return and live with their birth parents.”

»It’s important that we stay awake!«

Anton Model, Son of the Ukrainian forced laborer Warga Taran

Danger through right-wing extremism in Europe

Today Anton often visits schools and talks about his fate and that of his mother. He wants to show people which consequences war can have. “What worries me a lot are right-wing parties the supporters of which continue growing in numbers. That’s terrible. And if you don’t do anything now, if you don’t say anything now against that, then there is the danger that this will happen again. In their eyes, it is all about power. That is my message to young people: Do not allow these people to seduce you. They bring only misery, suffering and death. This is what we are experiencing now with the war in Ukraine. That’s where you have to be vigilant. It concerns me greatly that they do not accept, do not recognize the liberal order. It’s important that we stay awake!”