A Family’s Odyssey

The Polish farmer Anastazy Abramczyk and his wife Kleopatra had three children—each born in a different country. Their life story is an odyssey brought upon them by political persecution.

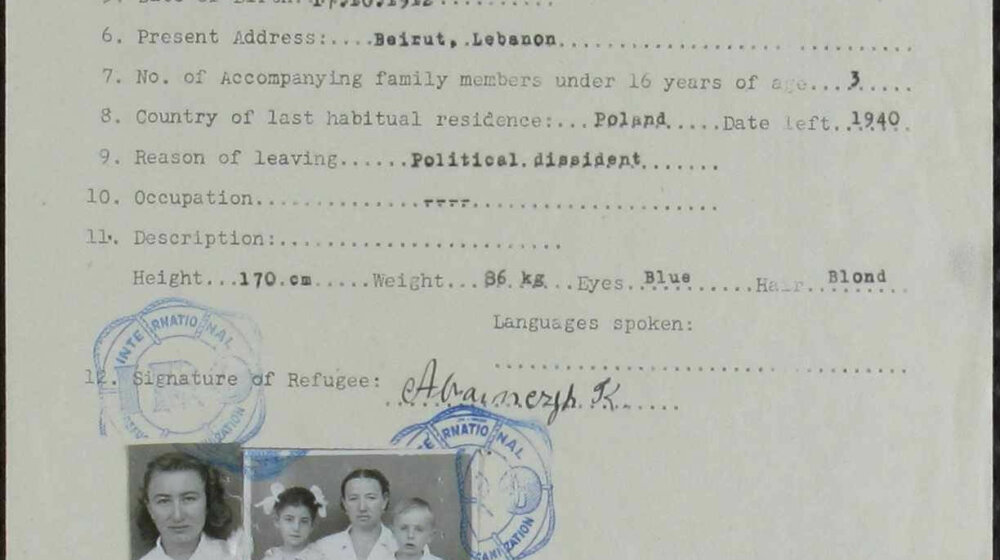

On November 25, 1947, the family filed an application for support with the International Refugee Organization in Beirut. A document in the ITS archive tells the story of their deportation and migration. They had lost their homeland in 1939, when Poland became a pawn in the hands of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

In the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the two countries had agreed, among other things, to divide up Poland between themselves. Just a few weeks after the Germans annexed the western areas of Poland, the Soviet Union took control of the east. In the two years that followed, more than a million Poles—including Anastazy and Kleopatra Abramczyk and their daughter Nadzieja—were deported to the Soviet Union.

Little is known about the family’s fate over the subsequent years except that they landed in Verkhnyaya Toyma, in the Arkhangelsk administrative division, where the parents were assigned to forced labor. The conditions in the camps were characterized by hard work, hunger and a lack of medical care. Many of the deported Poles died.

When the Germans violated the non-aggression pact in July 1941 and invaded the Soviet Union, the Soviets joined forces with the Allies. The Polish prisoners were granted amnesty. Some 116,000 of them were taken to occupied Iran. The Abramczyks arrived in Tehran in August 1942. There, however, the facilities charged with caring for the many refugees proved insufficient.

Starting in the summer of 1942, other British colonies therefore began to take in Poles from Iran. On February 5, 1946, less than a year after the birth of their second daughter Maria, the Abramczyks found themselves in Beirut, Lebanon. Their son Jerzy was born there in November 1946.

In July 1950, the family tried to emigrate from England to Canada. Anastazy’s sister-in-law lived there and had promised to help them gain a foothold in the new country. The Abramczyks were afraid to go back to Poland for fear of being arrested all over again—as grounds for deporting them, the Soviets had classified them as political dissidents.

Documents about the Abramczyk Family are available in our Online-Archive