Files on children’s fates in and after the Nazi era

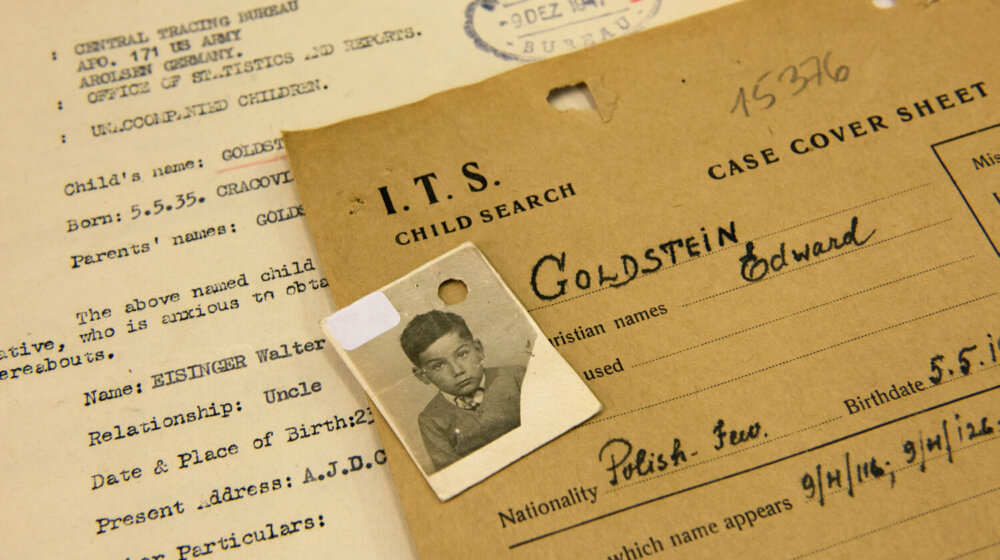

When the war ended, there were millions of survivors of Nazi persecution in Europe. They included liberated concentration camp inmates, prisoners of war, people who had been deported as forced laborers – and tens of thousands of children left to fend for themselves. The predecessor organization of the Arolsen Archives set up a special child tracing service to reunite them with their families. The Child Search Branch recorded the fate of each individual child. Poignant documents, such as questionnaires, interviews, and memos, bear witness to this work.

Over 64,000 child tracing files are stored in the Arolsen Archives. Most of the documents were produced between 1945 and 1951. In addition to factual information, they also record the children’s hopes and dreams. Despite everything they had been through, they longed to make a new start. Who were they? Children who had survived ghettos and concentration camps, children born to forced laborers, and others who had been deported and forced to work themselves. Some of them were Jewish and had endured years of persecution hidden away in their neighbor’s houses. Others had been torn away from their families in Eastern Europe to be “Germanized” in Lebensborn homes. This sub-collection contains information about their fates too – in the form of transcripts of documents that date back to 1940. Other files document the efforts made to find missing children.

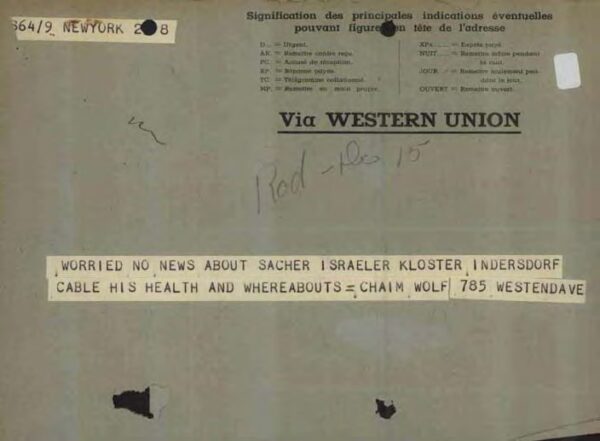

The Child Search Branch also dealt with inquiries submitted by relatives of missing children. Many had fled from the Nazis and gone into exile in places like New York.

The aim of the Child Search Branch was to reunite families.

Giving the children a voice

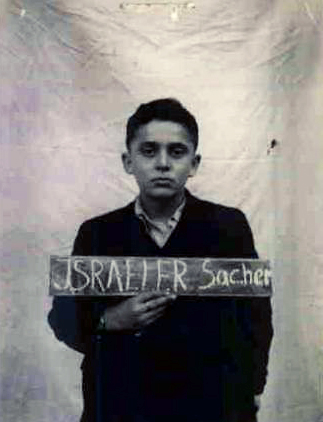

The child tracing files document the children’s identity, their ordeal, and the efforts made to reunite them with their families. They contain questionnaires and written records of conversations with the children, medical records, and personal impressions recorded by the caregivers in the special children’s centers set up to look after them. Kloster Indersdorf, a former monastery in Bavaria, was one such children’s center. And one of the children to find a temporary new home there was 14-year-old Sacher Israeler, who spent a short time at Indersdorf in October 1945.

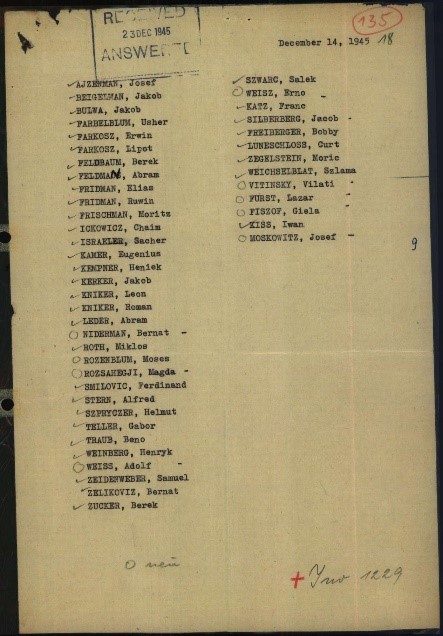

This list, dated December 14, 1945, details the names of children at Kloster Indersdorf who had relatives outside Germany. Sacher Israeler was one of them.

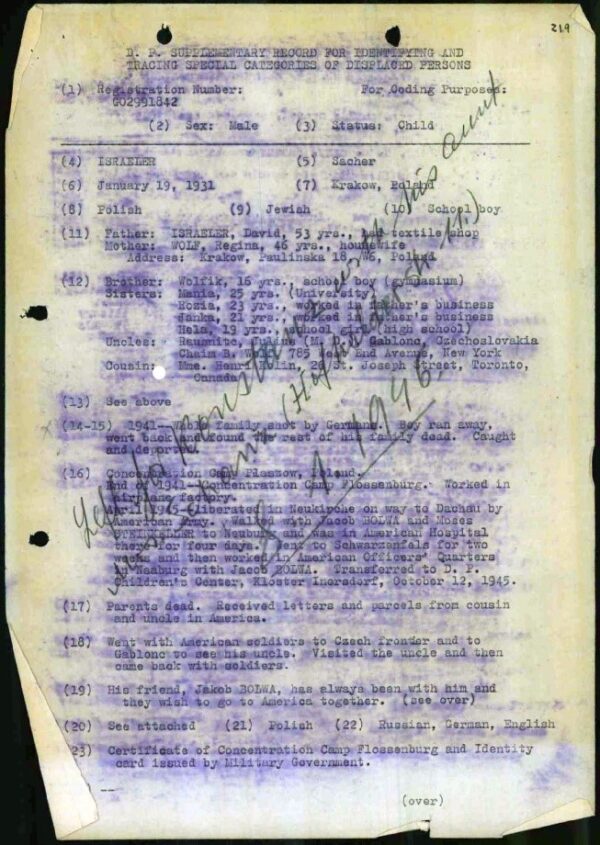

Deported from Poland: Sacher Israeler

Sacher Israeler had experienced unimaginable suffering. He and his family were Jewish, and they had fled from Krakow to Tarnow in 1939. His mother and his two sisters were shot dead in the street there, his father died of his gunshot wounds later on. Sacher was deported to the nearby ghetto, later he was transferred to Plaszow concentration camp. Initially he was sent to an aircraft factory, where he had to perform forced labor. From there, he was sent on to Auschwitz concentration camp and finally to Flossenbürg concentration camp. At the end of the war, he survived the death march to Dachau before being discovered by US soldiers and taken into care. After a stay in a military hospital, he finally arrived at the Kloster Indersdorf children’s center.

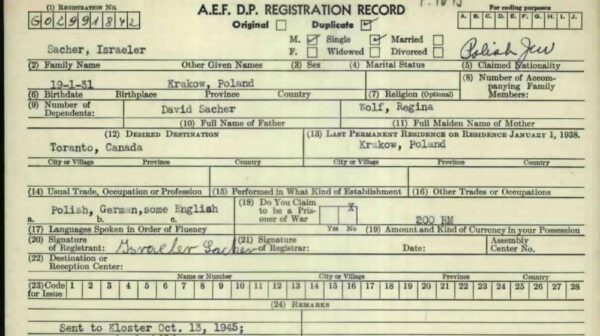

Displaced Person (DP) registration card for Sacher Israeler, he specified Canada as his preferred destination.

UNRRA form for displaced persons. It outlines the ordeal 14-year-old Sacher Israeler had been through.

Documents from the specially established children’s centers

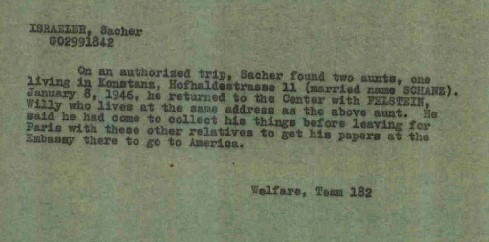

Sacher was given clothing, food, and everyday necessities at the Indersdorf children’s center. The children also received medical care and psychological support if they needed it. Those who were old enough were interviewed individually. Notes on the youngest children record the staff’s observations – how the children reacted to people and whether they were ill or cried a lot. These procedures show that the children in these centers were seen as individuals with a unique history and with dreams and wishes of their own. The files are an important source of information on how the youngest survivors were cared for after 1945. They also contain information about their later lives. The Child Search Branch found Sacher’s aunts and uncles in the USA and Canada. His Aunt Anna had survived detention in a concentration camp too, and she was still in Germany. They met up again in Constance in January 1946 and decided to travel to America together via Paris. They arrived there in 1947.

Note from the child tracing file concerning Sacher Israeler’s whereabouts after he had left the children’s center.

Work went on for decades

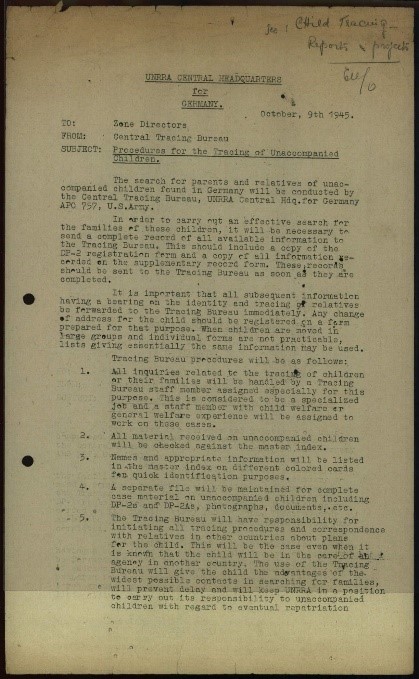

The Child Search Branch (CSB) was part of the International Tracing Service (ITS), as the Arolsen Archives used to be called. Initially, the Tracing Service was under the direction of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), the largest and most important aid organization of the post-war period. UNRRA also ran the children’s centers and worked closely with other aid organizations, including Red Cross offices and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

The Child Search Branch was first based in Wiesbaden, then in Ludwigsburg, and finally in Esslingen am Neckar. Its staff included field officers who followed up on leads provided by the public and searched in German children’s homes and in families for children of forced laborers and for children who had been abducted.

The Child Search Branch received 27,837 inquiries in the early years up until August 1950. According to an overview in an activity report from 1951, the Child Search Branch managed to find 17,341 unaccompanied children in the first six years after the war. A contrasting figure highlights the tragic situation the children faced – in only 4855 cases did staff succeed in finding relatives. In 1951, all the documents from the Child Search Branch were sent to the ITS in Arolsen. Active field searches were phased out. Nevertheless, the ITS continued the search for decades. The work involved contacting international Red Cross offices and survivors’ associations, sending inquiries to local authorities, consulting church registers, and a host of other activities. Cases are still solved today: the true identity of a stolen child might be discovered, for example, or an adopted child gets to know their half-siblings after submitting an inquiry to the Arolsen Archives.

The extensive surviving files are still an important resource today, as they make it possible to gain an understanding of the suffering of children persecuted by the Nazis while acting as a warning to future generations. Online access to the child tracing files is restricted for reasons of data protection. If you would like to obtain access to them, please contact our Archives team.

Detailed description of the procedures and responsibilities of UNRRA’s child tracing service, dated October 9, 1945