On the trail of Dutch forced laborers

Fred Seesing, himself the son of a Dutch forced laborer, heard about the #everynamecounts initiative of the Arolsen Archives for the first time on a German TV program broadcast in March 2021. The initiative invites volunteers to record data from Nazi documents in digital form to make the information they contain available online to people all over the world. Since then, the 67-year-old who was born in Rotterdam has indexed more than 2,700 documents – and solved a few mysteries connected with victims of Nazi persecution along the way.

“Thanks to the archive in Bad Arolsen and #everynamecounts, some really positive things are happening.” These were the opening words of Fred Seesing’s first message to the Arolsen Archives in the fall of 2021. He then went on to tell the story of Dutch resistance fighter Dirk Kleiman, who was murdered in a penitentiary in Saxony, Germany, on March 15, 1945. For many years, no one knew where he was buried. But Fred Seesing started to do some research in the Arolsen Archives and found information on his final resting place, which he passed on to the victim’s grandchildren: “Seventy-six years after Dirk Kleiman’s burial, they now know where their grandfather’s grave is. Without your online archive, this would never have been possible.”

But the mystery surrounding Dirk Kleiman is not the only one that Fred Seesing has been able to solve with his research. The pensioner, who has been living in Germany since 1973, spends four to six hours a day exploring documents, names, and fates – some connected with his own family. The Nazis deported his father Cor Seesing and his father’s brothers Jan and Nol from the Netherlands to Brandenburg an der Havel for forced labor; the youngest brother Theo was sent to Vienna. Cor, Jan, and Nol had to work for various companies in Brandenburg an der Havel, including the Adam Opel AG factory and the Excelsior bicycle factory, where they made parts for machine guns.

“De weg naar huis” – The way home

At the end of April 1945, they decided to flee. Their plan was to walk 70 kilometers to the River Elbe and return home from there on a transport organized by the Americans. The eldest brother Jan kept a diary during their journey, which ended up being over 200 kilometers long because they took various detours. The last entry is dated May 10, 1945, shortly after they had heard that the Germans had surrendered: “We shouted with joy. And if we hadn’t been so tired, we would have jumped, too.”

»We shouted with joy. And if we hadn’t been so tired, we would have jumped, too.«

Jan Seesing, entry in his diary shortly after the German surrender

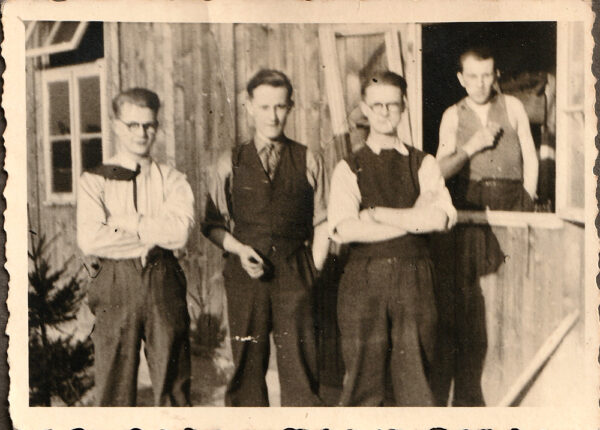

From left to right: brothers Nol, Cor (Fred Seesing’s father), and Jan Seesing standing in front of a wooden hut on the Opel site in Brandenburg an der Havel.

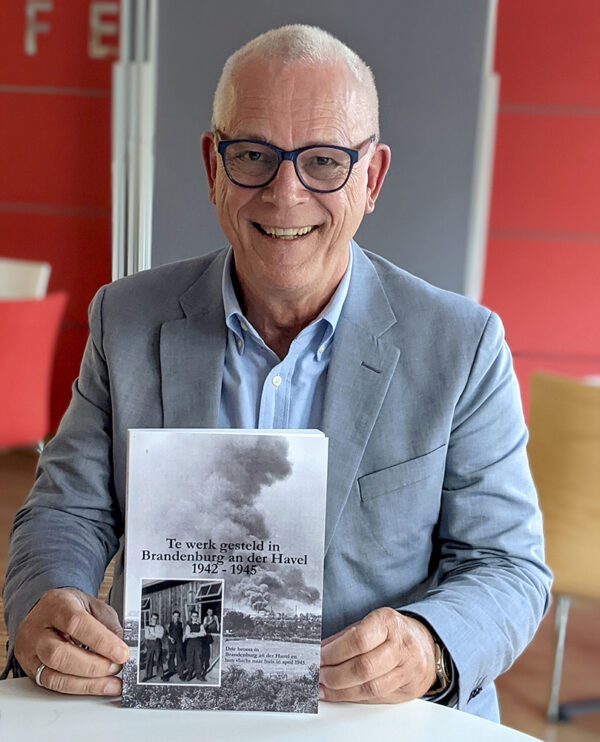

Fred Seesing knew his father had been a forced laborer: “But unfortunately, I didn’t ask enough questions.” Cor Seesing died in 2009. At the funeral, his son was given his uncle’s diary, and he read the whole thing on the way back to Germany: “I knew I was holding something really interesting in my hands.” He started to transcribe the handwritten pages, reconstructed the routes the brothers had taken each day, and eventually he even traveled to Brandenburg with his family to retrace their journey. He put the results of his research together to make a book which he had bound, a chronicle for all the members of the family. He also translated parts of it into German. In 2021,a local history club, the Heimatverein Burg und Umgebung e.V., published the diary complete with Fred Seesing’s notes under the title “Der Weg in die Freiheit dreier holländischer Zwangsarbeiterbrüder” (The path to freedom of three Dutch brothers deported as forced laborers).

The last of the three Seesing brothers died in 2017 at the age of 96.

Fred Seesing with his family chronicle “Te werk gesteld in Brandenburg an der Havel 1942 – 1945” (“Forced Labor in Brandenburg an der Havel 1942 – 1945”)

Tracing his own family history

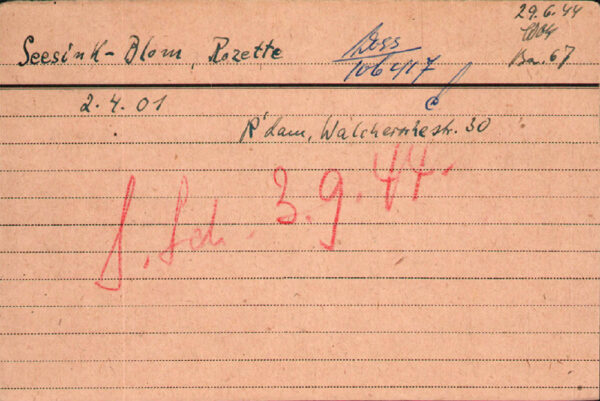

The Arolsen Archives hold a number of documents about the Seesing family, including records on Fred Seesing’s great-aunt Rozette Seesink-Blom, who had the surname “Seesink” instead of “Seesing” because a registrar spelled her surname wrong when he wrote it down.

She was deported to Auschwitz from the Westerbork transit camp in September 1944. Westerbork was one of two assembly camps in the Netherlands. More than 100,000 Jews, Sinti, and Roma were deported to concentration and extermination camps in the East from there. Rozette Seesink-Blom probably died on a death march in January 1945. A list of names of Jewish victims of the Nazi regime in Holland from 1941 to 1945 includes the following information about her: “Plaats en Datum van Overlijden: Midden Europa, 21.01.1945.” (Place and date of death: Central Europe, 21.01.1945.)

In connection with his research on “Aunt Roos,” Fred Seesing was also confronted with the “dark side” of the family’s history. It was actually quite uncommon for a Jewish woman in a so-called “mixed marriage” to be deported. But according to information that Fred Seesing found in the National Archives of the Netherlands in Den Haag, Rozette Seesink-Blom’s husband betrayed her after she left home, taking their two children and the furniture with her. Her husband threatened to denounce her as a Jew if she did not return the household goods. When he reported her, Roos was deported to Westerbork. “When you read things like that, it sends shivers down your spine,” explains Fred Seesing.

Index card from the Jewish Council card file in Amsterdam for Rozette Seesink-Blom

When he sees documents like Rozette’s index card, it moves him for many different reasons: “The moment I pick up a list or a card, maybe even one with a signature, all sorts of thoughts go through mind. What must it have been like for my great aunt in Westerbork to know that a train left for Auschwitz every Tuesday?”

Rozette Seesink-Blom was assigned to barrack 67 in Westerbork, which was a punishment block. She was locked up there for failing to comply with the “compulsory registration of persons wholly or partly of Jewish blood” in February 1941. Fred Seesing has already visited the camp: “I stood in front of this barrack where she spent her last days before she was carted off on a train to Auschwitz. I felt as if I was walking in my great aunt’s footsteps.”

Working to preserve the memory of the victims

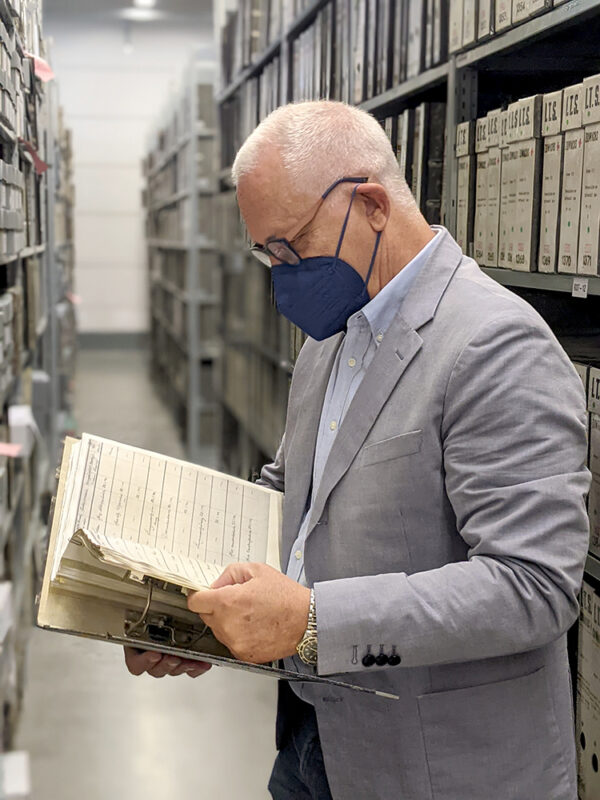

Fred Seesing’s research skills are now quite sought after: “After a while, people started coming to me and saying: Listen, Fred, could you take a look at this for me…” He recently traveled to Bad Arolsen to do some research on things people had asked him to look into. He spent three days searching through various databases, discovering new names, and finding out more details. And despite the fact that working with the documents is quite routine for him now, the fates they describe do not leave him cold: “My wife is always telling me not to let it get to me too much. I’m the kind of person who really immerses themselves in a story, I can see it all happening right before my eyes.”

»When I turn on the TV, I see that antisemitism is coming back. How can that be? Haven’t we learnt anything from the past?«

Fred Seesing

He has even managed to inspire his daughter to take part in #everynamecounts and start indexing documents herself. And Fred Seesing would really like to go into schools and talk to students about how documents can help clarify the fates of victims of persecution – especially now that hardly any contemporary witnesses are still alive. “I think it’s very important. When I turn on the TV, I see that antisemitism is coming back. How can that be? Haven’t we learnt anything from the past? By making the data from the Arolsen Archives available online, you’re helping to make sure the victims are remembered.”

Frank Seesing looking at documents in the archive building of the Arolsen Archives

Another motivating factor is the contact he has with relatives and the knowledge that the research he does can help them. When Fred Seesing found out the place in Waldheim (Saxony, Germany) where resistance fighter Dirk Kleiman is buried, he received the following message from his relatives: “Many thanks once again, especially for the photos taken in Waldheim. While we are unable to imagine the darkest day in Dirk Kleiman’s life, the photos at least give us a glimpse of his final resting place.”

“And that’s why I keep on working,” adds Fred Seesing with a smile.