Rudolf Brazda: "They didn´t destroy me"

For three years, Rudolf Brazda went through the hell of Buchenwald Concentration Camp, and survived. 96-year-old Brazda was one of the last known former inmates from the group of homosexuals persecuted by the National Socialist regime. In 2009 he visited the Arolsen Archives.

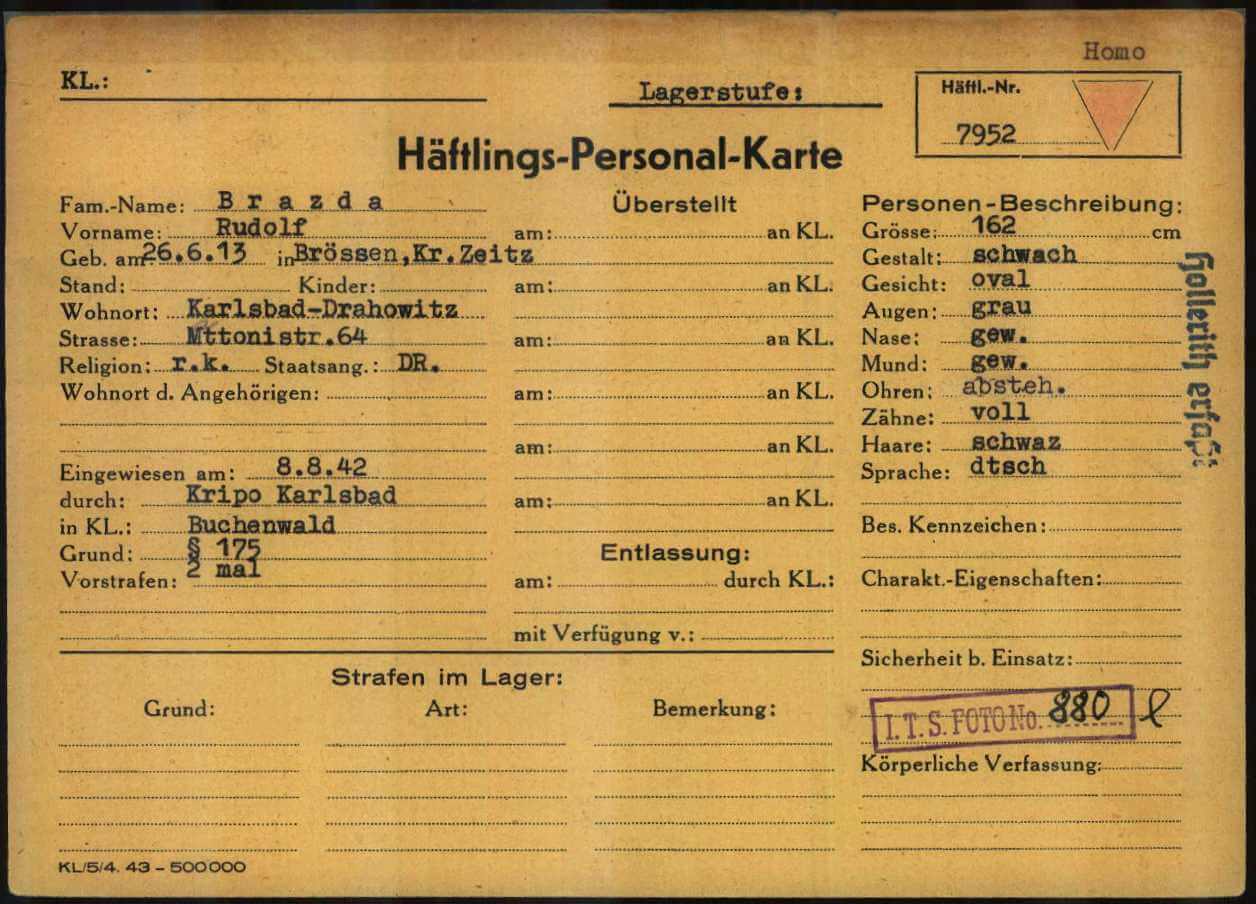

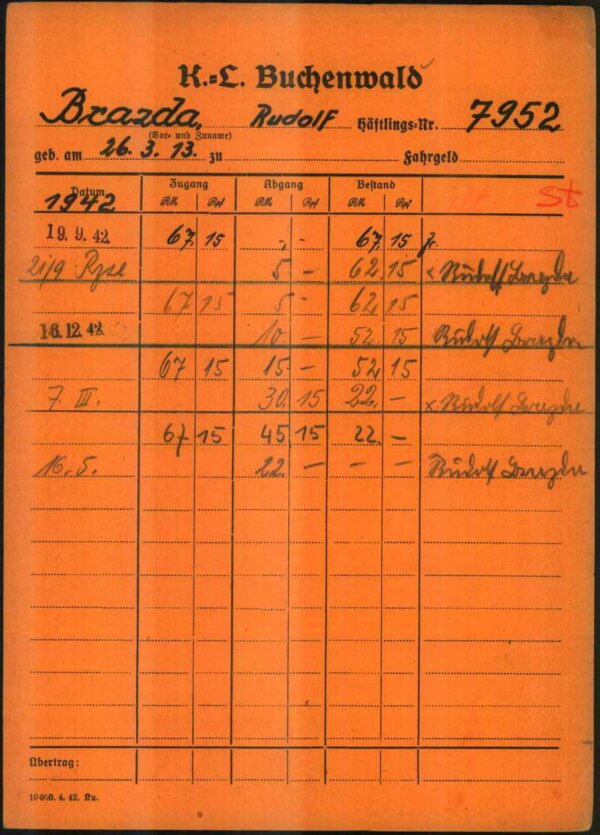

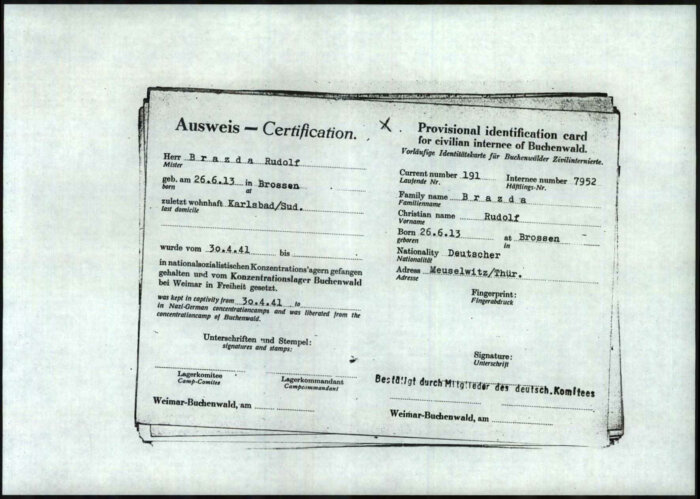

“I am not railing against my fate. I am thankful that I am still fit”, said Brazda with a smile. After 64 years, in November 2009, Brazda viewed his original documents from Buchenwald Concentration Camp for the first time – “Committed to the camp on 8th August 1942, § 175 homosexual, prisoner number 7952, pink triangle” – entry list, effects’ card, prisoner’s identification sheet. In stark words, the bureaucracy of horror lists the stages of his degradation.

“I have drawn a line under my past”, commented Brazda as he looked at the documents. But his memories of the time of his suffering still sounded fresh. He first experienced the brutality of the new regime whilst at a coffee-shop called “New York”, a well-known gay meeting point in Leipzig. “The SA pulled us out, dragging us by our hair.” Following the closure of the pubs and gay centres, the systematic persecution of homosexuals began. About 50,000 men were sentenced, and around 10,000 were deported to concentration camps where they had to wear pink triangles on their clothes. More than half of them were murdered.

The Nazis first imposed a six-month prison sentence on Brazda in Altenburg in 1935 for having had “unnatural fornication”. Subsequently, they deported the native Saxon to Czechoslovakia. After the German occupation of the Sudetenland in October 1938, Brazda had to fear every day that he would once more be arrested by the Germans.

»We were like wild animals being hunted at the time. Wherever I went with my boyfriend, the Nazis were already there«, recalled 96-year-old Brazda.

On 1st April 1941, Brazda was imprisoned for 18 months and subsequently deported to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. As a rule, homosexuals were used for the heaviest labour at the quarries. The chances of survival were negligible. But Brazda was lucky, “as at so many times in my life”. A Kapo fell in love with the young man and sent him to a less exhausting labour commando to work as a roofer, his original trade.

Shortly before the end of the war, another Kapo hid him for three weeks in the tool shed of a pigsty. This is how he escaped the death marches. On 11th April 1945, the US army finally liberated the camp. “I am no longer afraid of anything”, said Brazda looking back. “Millions of people were broken. But they didn’t destroy me.” After the war, Brazda settled in Alsace and shared his experiences with the younger generation of gays and lesbians. “They can consider themselves lucky to live in a free democracy.”