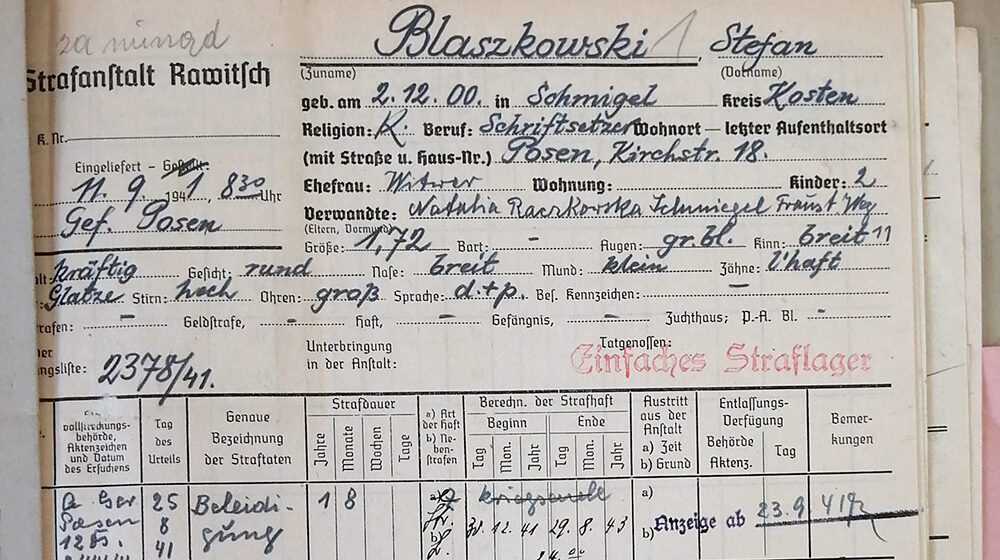

Accused of being homosexual: Stefan Blaszkowski

Stefan Blaszkowski spent almost two years in prison because a German Gestapo man accused him of being homosexual and claimed to have been insulted by him. The mere suspicion was sufficient to convict Stefan. This example shows that Paragraph 175 could also be applied in cases that did not involve intimate relationships.

A trial against Stefan Blaszkowski, who was born in Śmigiel, Kościan County, in 1900 and resided at Kościelna Street 18/22 in Poznań, took place before the District Court in Poznań on August 25, 1941. The defendant was accused under Paragraph 175a (4) and 185. Stefan was initially under investigation as a male prostitute and because he allegedly insulted a German, a certain Köster.

The witness statements given by Blaszkowski and Köster are missing from the file – only a police report taken down by the interrogators has survived:

“On June 17, 1941, the accused visited the public lavatory located under the Arkadia café on Plac Wolności in Poznań. The witness Köster was also there in plain clothes as an officer of the Secret State Police on the day in question, but wore the SS symbol. When the witness Köster left the public lavatory, the defendant followed him and asked him where he wanted to go with him, as there was nothing to do there. Based on all the accused’s behavior, the witness Köster immediately came to the conclusion that the accused was a homosexual. The accused explained that he knew about a room belonging to a Polish man, where they would be completely undisturbed. When the witness Köster refused, the accused eventually asked the witness whether he perhaps knew of a better opportunity. The witness Köster subsequently took the accused to the 1st police precinct, where he was arrested.”

One person’s word against another’s

During the main hearing, Stefan Blaszkowski defended himself and claimed that it was the other way round. It was a German who had attacked a Pole. He first laughed at him “shamelessly” in the municipal toilet and then – already outside – offered him a cigarette. He wanted to see the man’s genitals, but the Pole refused. He did not want to expose himself in the street, but was willing to meet under more favorable circumstances.

Köster denied this. According to him, the accused was a nuisance, and this was viewed as an insult. At the same time, the Pole’s unusual behavior, according to the judge, showed that this was not the first such situation in Blaszkowski’s life, and that he probably made such offers regularly: “It must, however, be noted that, as a Pole, the accused did not shy away from inviting a German, who was even known to him as a member of the SS by the symbol, to engage in homosexual intercourse and also to allude to a favorable opportunity in a Polish man’s room.”

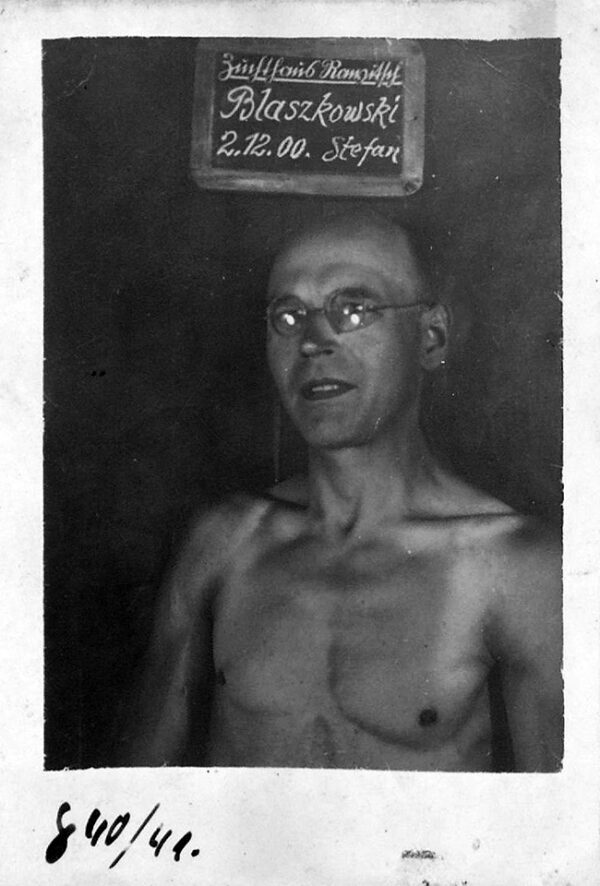

Photo of Stefan Blaszkowski taken in the Rawicz penitentiary. Copyright: Archiwum Państwowe w Poznaniu

The Pole’s behavior, which was interpreted as an “invitation to engage in homosexual intercourse,” was one of many examples given for the “danger of a broad influence.” The combination of the alleged insult and Paragraph 175 meant a higher penalty. Blaszkowski’s attempt to shift the blame onto Köster and his insistence on proving his own innocence also spoke against him. As a result, the time spent in prison until the day of the hearing (two months) did not count towards the sentence.

A suspicion was enough

The most striking part of Blaszkowski’s story is that Paragraph 175 could also be applied in cases that did not involve intimate relationships. All that was required was a suspicion of “malicious intent.” There are no specifics here – there are vague suggestions, vague undertones that build up during the hearing, that grow into hard evidence, and the homosexual character of the chance meeting of both men is above all a result of the specific location – a municipal toilet and the interpretation of a Gestapo officer. All of this was sufficient to set the Pole up for prosecution. It was very likely that Blaszkowski’s version was closer to the truth. Perhaps Stefan had rejected the German or the Gestapo man had intentionally provoked the Pole. Köster’s advantage was above all the fact that he took Stefan to the police precinct. Perhaps he cooled off after some time and became afraid of the punishment that an SS man could expect for a homosexual relationship – especially with a man of Polish origin.

Two years in prison

Blaszkowski, a typesetter by trade, professed the Catholic faith. He completed seven years of elementary school. He was widowed in February 1940. His father died one year later. He had two minor children – Christine (nine years old) and Witalis (five years old) and could pride himself in having a clean file. He worked as a printer at the “Ostdeutscher Beobachter” newspaper, among other places. Once his imprisonment ended, he wanted to return to his job. He wrote in his résumé that he suffered from a kidney disease, cardiac neurosis, rheumatic pain, and a visual impairment.

In the second half of September 1941, he was moved from the prison in Poznań to Rawicz. He weighed sixty kilograms at the time. He was due to be released at the end of August 1943 – after twenty months in prison and four months in pre-trial custody.

At the beginning of January 1942, Natalia Blaszkowska wrote a short letter to the prison authorities in Rawicz and asked for a meeting with her uncle. The woman’s parents had already died, but Stefan remained her only relative. She wanted to discuss an important family matter with him. The woman lived in Śmigiel, where Stefan had been born. She received a permit for a visit that was only to last fifteen minutes. Blaszkowski died from pleurisy (“cardiac insufficiency”) five months before he was to be released. The death certificate was issued on March 22, 1943.

Note by the author Joanna Ostrowska:

In the past few weeks, as part of Pride Season, we have featured three Polish men who were convicted under paragraph 175, but they do not exist in the Polish collective memory because of homophobia. Today it is impossible to establish for sure, what was their gender identity or sexual orientation. Two of them survived the WWII and came back to Poland, but they haven‘t left their testimonies. Probably they didn‘t have any opportunity to talk about their past also with their families, or they decided to be silent.

Nevertheless, their biographies are a really important part of queer history of WWII in Poland.

A guest article by Joanna Ostrowska