After the Holocaust: Keeping Silence in Hungary

Many families were left speechless at the end of the Second World War. In some cases, this inability to talk about their experiences continues to this day. Marianne Kiss ended the silence and wrote a book about her family history.

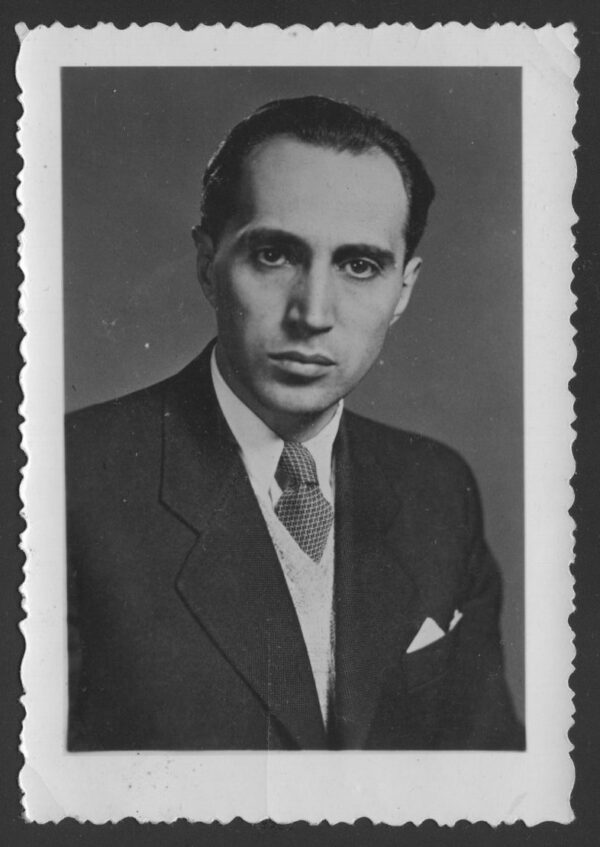

Marianne was nine years old in 1944, when her mother Ilona last heard news of her husband, Marianne’s father Arpad. Later, the family assumed that Arpad had been deported to the Bor labor camp in what is now Serbia. Ilona did everything she could to search for him. Marianne descirbes her efforts as follows:

“That you did not just wait idly, but actively searched – letters, documents testify to that. (…) You knew one thing for sure: if Arpad is alive, he will move heaven and earth to make his way home to his family. But he never arrived. The Red Cross sent you an answer on May 27, 1946, telling you that no definite information had arrived yet. The Vatican Information Office also wrote the same in German.”

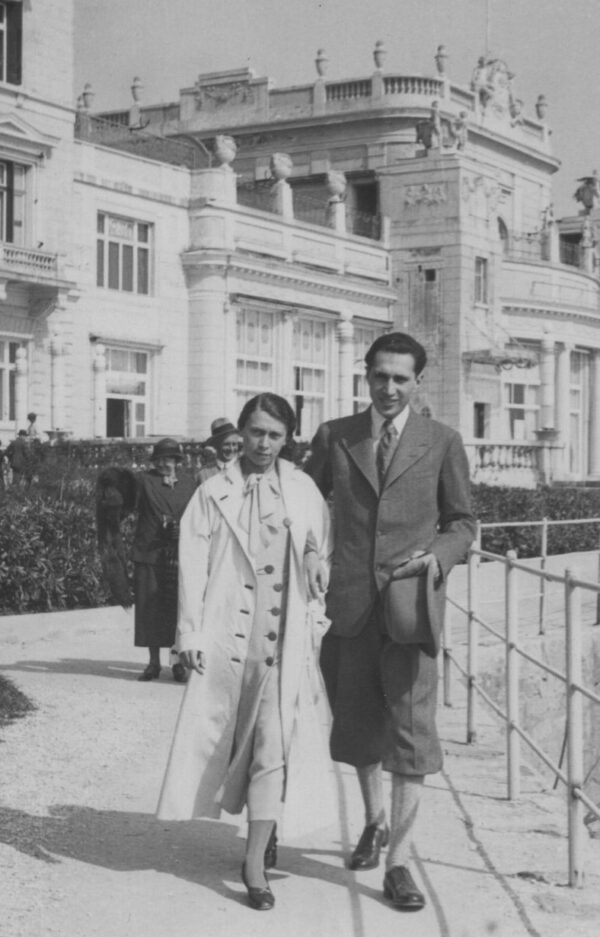

Marianne’s parents at their wedding, 1934. © Marianne Kiss

Die Schwarczmanns on their honeymoon. © Marianne Kiss

Research in the Arolsen Archives

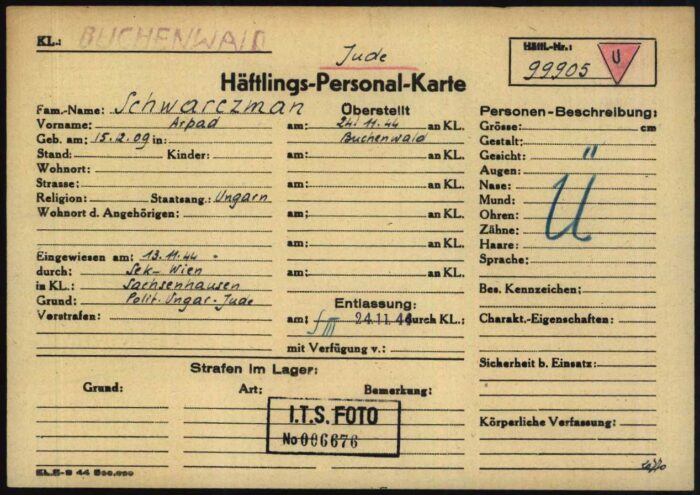

Many decades later, Marianne found out that the Nazis had deported her father to various concentration camps, including Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, and the Buchenwald sub-camp Ohrdruf. On January 15, 1945, Arpad Schwarczmann’s name still appeared in a change report from the Buchenwald concentration camp about prisoners assigned to the Ohrdruf labor detail. After that, all trace of him was lost. In 1985, Marianne contacted our archives for the first time, wanting to learn more about the fate of her father.

In addition to grief, there was also a kind of anger at her father. She puts it like this:

“Father was a taboo subject, because whenever we mentioned him, the pain of talking about him only in the past tense was too great. Later, I (secretly) resented him for not trying to hide, to escape, despite his great love for us.”

From Hungary to Ohrdruf

The Nazis deported Arpad from Vienna to Sachsenhausen concentration camp on November 13, 1944. On November 24, 1944, they sent him on to Buchenwald concentration camp along with 499 other Sachsenhausen prisoners, the overwhelming majority of whom were taken to Buchenwald’s Ohrdruf sub-camp that same day – including Arpad Schwarczmann.

Even today, at the age of 87, Marianne is still working on coming to terms with her family history, and she began to write it all down in 1997 – after the death of her mother. How important this writing process was for her comes through very clearly in the first lines she addressed to her mother:

»Dear Mom! It is to you that I write and to you that I address my letter, which for the most part contains what I know about you, yet I feel it is important that we clarify some things between us. Unfinished business that we have never talked about, either because we did not want to do so or could not do so. Now the time has come. I’m trying.«

Marianne Kiss, Author and graphic designer

Childhood memories of Hanukkah

In her book, Marianne also describes her own childhood memories. Beautiful memories of Hanukkah, for example: “A Christmas celebration was out of the question for us, Hanukkah was the festival in winter, close to Christmas, that’s when we children got little presents.”

In the same paragraph, she describes what a shock the persecution of the Jews must have been for her grandfather:

“I only ever saw my grandfather Hajnal with a prayer shawl and prayer straps on his arms when he was in the synagogue; on ordinary weekdays it never occurred to him to pray. He was an enlightened man, the concept of assimilation could have been invented for him. The anti-Jewish laws must have hit him like a cold shower.”

»How could it be that he, such a far-sighted, well-traveled man, had never heard of all the atrocities that were going on in Germany? Like many others, he had not taken the approaching danger seriously.«

Marianne Kiss, Daughter of Ilona and Arpad Schwarczmann

Surviving in the air raid shelter

Marianne herself survived the Holocaust in her hometown of Budapest as a child in air raid shelters, and to this day, she helps preserve the memory of the Hungarian victims of the Shoah. Because education, in her opinion, is the key to combating antisemitism.

Read the interview with Marianne Kiss

In the interview, Marianne talks about the silence in Hungary and how she got the idea to write down her family history.

Did your family talk about the period during World War II?

In Hungary, there was a great silence about Nazi persecution after the war. I think this was an unspoken political decision taken by the Communist Party. My family and other families also kept silent. First and foremost, we were happy to be alive and did not want to remember the horror. In school, the history books did not have a single sentence about the persecution of the Jews. They wrote about “people who were persecuted”, but they referred to the “illegal communists,” never to the Jews. Religious education stopped being taught in schools.

What did people say about the labor camps and the concentration camps?

I have two uncles and an aunt who were in concentration camps – in Theresienstadt, Lichtenwörth, and Bergen-Belsen. They came home at the end of 1945 and 1946. They were very skinny, and my aunt, who was a beautiful woman, had no hair – she had typhoid fever after the war. But the interesting thing is that they never talked about what happened to them in the camps. Maybe they talked to my mother or my grandmother, but I was only a 10-year-old child, they didn’t talk about it in front of me.

How did Jews live in Budapest after the war? How was your family integrated into society?

After the war, Jews and non-Jews were in a very difficult situation. Budapest was in ruins – and my mother and the other relatives helped to clear the rubble day after day. They got one or two cups of tea for from the city government in return. After school, I wanted to study at university, but I was a “black sheep” because my birth certificate listed my father’s profession as “shoe manufacturer,” and for this reason I was excluded from all the universities in Hungary. I was good at drawing and found employment, first as a cartographer and later as a graphic artist – there are many books with my graphic works. (In 1985, I had a successful exhibition).

When you were sorting out your mother’s estate after her death, you found letters that cover a lot of your family history. What new information did you obtain in this way? What surprised you the most?

After my mother’s death, I found a large package of family letters. The biggest surprise for me was when I found all the letters from the time when my father was in the labor camp and he and my mother were trying to contact each other. Later, I put all these letters in the right order and printed them out (only for me and my dear daughters).

What gave you the idea to write and publish a book about your family?

The idea to write and publish a book about my family came to me after my mother died. I love the big family of my mom, my dad, and my grandparents, and I wanted to memorialize them. And in this book, I mourned my deceased loved ones.

How do you feel about the commemoration of the Holocaust in Hungary today?

There are many commemorative events in Jewish circles in Hungary today. But in my opinion, people on the street don’t like it at all, and they complain about it.

What can we do to combat antisemitism, persecution, and hatred?

Oh dear, maybe education can help. But when I look around, most countries are right-wing and have problems with antisemitism.

How do your children and grandchildren see their family history today? Are they interested in it?

My daughter has helped to maintain Jewish remembrance, she has procured Stolpersteine (commemorative plaques) for many people and ordered them from Mr. Demnig. My father and grandfather also have Stolpersteine in front of their home, their last permanent place of residence. My grandchildren are also interested in hearing the stories, and they participate in the events.

Marianne’s notes were published in 2015 in “Yellow-Star Houses, People, Houses, Fates.” The text has been translated into German, but Marianne is still looking for a publisher who would like to publish it. If you are interested, please send an e-mail to pr@arolsen-archives.org.