All about the documents you’ll be indexing on the "Long Night of the Digital Memorial"

On the “Long Night of the Digital Memorial”, which will be held on November 9, volunteers from all over the world will be indexing documents from Dachau concentration camp that show a sudden increase in prisoner numbers during the November pogroms in 1938. We’ve been talking to Albert Knoll from the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial about the context in which the documents were created and about why they are so significant.

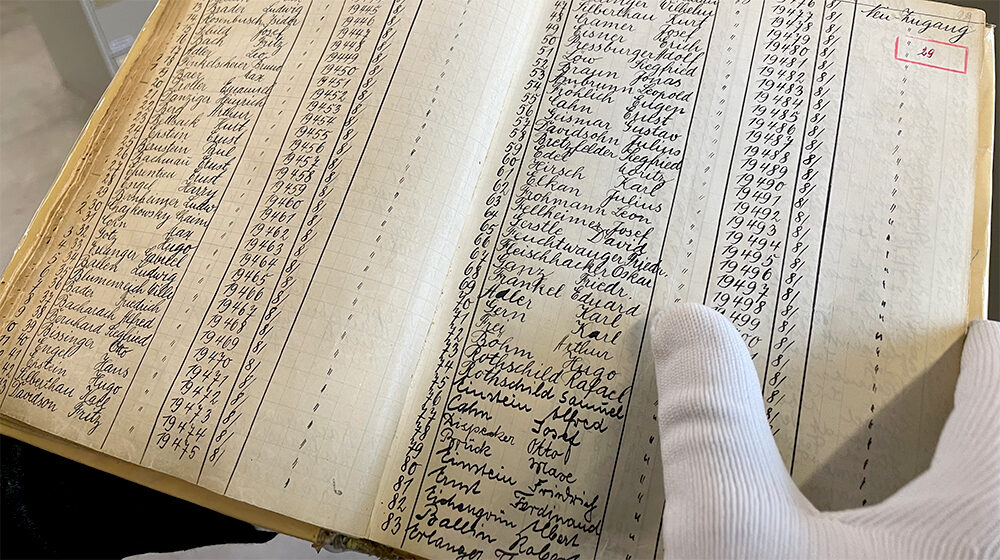

November 9, 2021 is the 83rd anniversary of the November pogroms. About 30,000 Jews were deported to German concentration camps already in the first few days after the beginning of the violent campaign – more than 10,000 of them were sent to Dachau. On the “Long Night of the Digital Memorial,” volunteers will be taking information contained in the camp’s so-called change reports and recording it in digital form to commemorate the victims of the November pogroms. By typing out the information on prisoners, they are helping to make these documents available in our online archive as part of the #everynamecounts initiative.

Albert Knoll is an archivist who has been working at the Dachau concentration camp memorial site since 1997. It would be nigh on impossible to find anyone more knowledgeable than he is about the documents that relate to the camp’s former prisoners.

Mr. Knoll, most of the change reports that our volunteers will be indexing on November 9 date back to the period around the November pogroms. What evidence of the pogroms can be found in the documents?

The November pogroms were behind the second major influx of prisoners to Dachau. The first influx consisted of the several thousand Austrian Jews who were brought in during the spring of 1938 at a rate of more than 500 per day. When I looked at the change reports and arrivals books, I realized that in November 1938, the prisoner clerks who were responsible for keeping the books hadn’t been able to keep up with the volume of work they had to do. The entry for November 15 is followed by November 26, and then November 15 again. This was the very first time that the camp’s system of so-called self-administration – a task imposed on the prisoners – was unable to cope. It was also the first time that the list contained this kind of irregularity – under normal circumstances, the clerks adhered to a strictly chronological order.

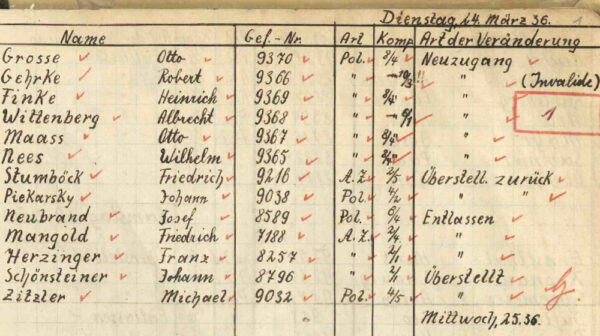

During the “Long Night of the Digital Memorial”, these so-called change reports from the Dachau concentration camp will be indexed.

On the “Long Night,” we will be focusing our efforts on indexing change reports. Can you describe them in more detail and explain how they differ from other documents like arrivals books?

The arrivals books contain more information. They include a prisoner’s name, date and place of birth, last place of residence, prisoner category, religious denomination, number of children, nationality, and profession. There are about twelve different fields in all. The change reports have much fewer fields. Their function was an internal one. They were used to find out where a prisoner was and who had entered or left the camp. Prisoners were sometimes transferred back to a camp, i.e. prisoners who were released for interrogation, for example, were sent back to the camp once their interrogation was over. Sometimes they were assigned a new number on their return and sometimes they weren’t, in which case they kept their old one. Such return transports are not recorded in the arrivals books, but they are recorded in the change reports. So by looking at the change reports, you really can track what happened on a day-to-day basis, a bit like you could with a diary.

How do they differ from the “registry office cards” that were indexed for #everynamecounts in the fall of 2020 already?

I’ve noticed that there are no registry office cards for any of the prisoners who were detained during the pogrom. Except for a few hundred of them who died in Dachau. I think registry office cards were probably created for all of them originally, but were removed later on, perhaps because it was assumed that these prisoners would emigrate anyway, so it wouldn’t be necessary to refer to their cards again. That’s the major difference when you compare them with the change reports, which contain every single name.

»There were barracks for new arrivals and for quarantine, and then there were barracks for prisoners who were to be released. Being able to trace where a prisoner was housed is very important for relatives who are looking for information about what happened to someone during their incarceration.«

Albert Knoll, Employee of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site

And is there any information about the prisoners that can only be found in the change reports?

Yes, the reference to the block number. This information is mentioned in the books that were kept by the sick bay clerks, but they weren’t introduced until 1944, and the change reports are the only other documents where this information can be found. They tell us which block Jews who were scheduled to be released were held in. That was usually a different block than the block they were assigned to when they arrived at the camp. If you compare these two entries, you can see that prisoners didn’t usually stay in the same block the whole time, but switched from one to another. There were barracks for new arrivals and for quarantine, and then there were barracks for prisoners who were to be released. Being able to trace where a prisoner was housed is very important for relatives who are looking for information about what happened to someone during their incarceration. Because then we can give them more information: a prisoner might have died in Dachau, and the cause of death might be unknown, but if barrack 17 is noted on the change report, or block 9, or another odd number, then we know that the person was in the sick bay. Or we can tell relatives that the prisoner may have been a victim of medical experiments and was in the tuberculosis block. This is important for us and for the relatives too, because then they know where they can lay a wreath or leave flowers, for example.

You also mentioned prisoners being released. But being released didn’t always mean that the prisoner was allowed to go home, did it?

Up until the beginning of the war, it was normal for prisoners to be released. This changed after 1940. As a rule, Jewish prisoners were only released if they could prove that they were going to emigrate. But not everyone actually succeeded in emigrating. We have some examples of November pogrom prisoners who got as far as the Netherlands or France, only to be arrested again, sent to Auschwitz, and then sent back to Dachau. There are a few cases like that, but we also know of prisoners who emigrated to the USA and returned to Dachau as liberators. Some of their stories are really fascinating. Some people only stayed in the camp for a week – but I don’t know if they would have been able to obtain confirmation of emigration in such a short time. Perhaps the people who were in charge simply decided to release a batch of prisoners because the camp was overcrowded. I don’t think anyone can say for sure.

What difficulties might the volunteers face when they record the information contained in the documents?

Most of the documents are relatively easy to read, but I think volunteers might have some trouble if the handwriting is spidery. Some of the daily reports were signed by members of the SS, for example. Their signatures are often very hard to decipher. But even if some information isn’t legible, the volunteers can indicate that something was written down. Then we can filter out the documents that contain illegible information and take a second look at them.

When we spoke earlier in preparation for this interview, you said that you often find notes like “2x in CC” (=”Several times in CC”) on the cards – which often meant that a prisoner was treated more harshly in the camp.

In a sense, this was a way of telling the SS to treat the person even more harshly, yes. It was even set down in the camp regulations, which include information on how “second-timers” were to be treated. There was no ban on releasing them, but it was important to identify them. In fact, I think some kind of mark on the prisoners’ clothing my have been used to identify them.

The Jourhaus

All new prisoners of the camp passed the “Jourhaus” (“Jour”: French, “day”) through its wrought-iron gate with the well-known inscription “Arbeit macht frei” (“Work sets you free”). In the writing room of the Jourhaus, the change reports were presumably kept.

Most of the names in the change reports are men’s names – are there any change reports about women? Am I right in thinking that the majority of prisoners in Dachau were men and that women were more likely to be held in the sub-camps?

Yes, women are definitely very underrepresented. The first women prisoners were a very small number of forced prostitutes who were brought in from Ravensbrück in the fall of 1942. After that, most notably from the summer of 1944 onwards, the vast majority of women who came were Jewish, and they were transferred directly to the sub-camps. In fact, when you look at the change reports from 1944 onwards, no one even bothered to draw up detailed lists any more. They just gave a summary indicating how many women came from France, for example, or how many protective custody prisoners there were, because there were quite simply too many prisoners to deal with.

Is there a story of a contemporary witness from the period around the November pogroms or a story connected with a prisoner who was incarcerated during the pogroms that particularly sticks in your mind?

David Ludwig Bloch comes to mind, prisoner number 21096, a Jew from the Upper Palatinate in Bavaria. He was sent to the camp on November 10 from Munich. He was deaf and visually impaired, and according to the list of arrivals, he was a “poster painter” and attended the School of Arts and Crafts in Munich. The amazing thing is that he survived Dachau despite that fact that he was deaf. In 1939, he emigrated to Shanghai and drew scenes from the ghetto. He gave us a fantastic oil drawing of a camp roll call from 1938. You can see details of the camp, 10,000 prisoners in the roll-call square, illuminated by lamps.

What happened to the change reports after the liberation?

It’s important to know that we are fortunate in Dachau in that a very large number of Polish prisoners with a good knowledge of German were brought to Dachau, especially from 1940 onwards. They were much sought-after as clerks for the registry office, and they stayed in the camp even after it was partially evacuated. They defied orders to destroy all records, and as a result, we know the names of a very high proportion (97 percent) of all the prisoners in Dachau. Only material that was in immediately accessible to the SS was destroyed. The former prisoners even continued to keep records – registry office cards were kept up-to-date until September 1945. But the change reports stopped on April 26 because there was no longer any reason to make further entries from that point on. And in 1947/48 the records were handed over to the International Tracing Service (now known as the Arolsen Archives).

On the Long Night of the Digital Memorial, we will be working together with volunteers from all over the world to add the change reports from Dachau to our online archive. Whether you have ten minutes or a few hours of your time to give, anyone can make a contribution and help ensure that future generations will be able to remember the victims’ names and identities. Register now for the “Long Night of the Digital Memorial,” and help us with this important work!