An artist searching for traces of her family

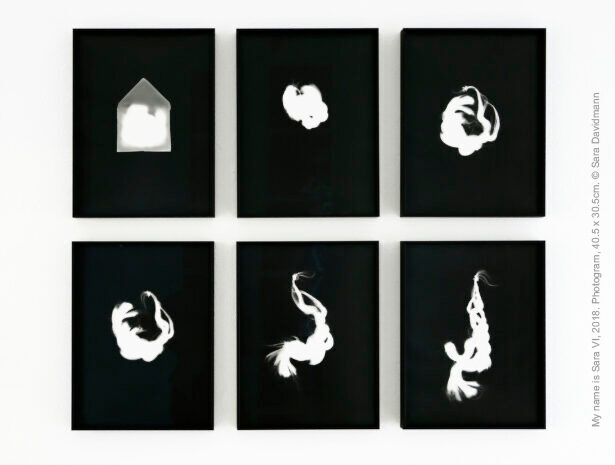

In 2016, the British artist and photographer Sara Davidmann found a photo album belonging to her aunt Susi, along with a few handwritten notes in German. The photos showed Susi’s life and that of her brother Manfred (Sara’s father) before and after the Holocaust. As a way of working through her family history, Sara Davidmann published the photos—together with documents from the Arolsen Archives—in the book Mischling 1 and displayed them in an exhibition in London with the title “My name is Sara”. The title of the exhibition was taken from a series of photographic artworks.

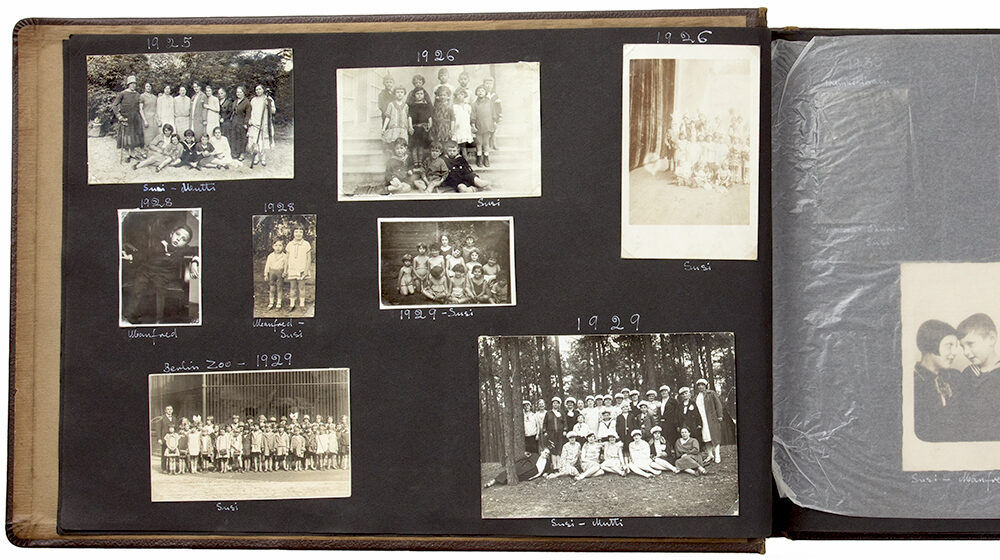

The early pages of the photo album show a normal, happy family life: vacation by the sea, weddings, excursions. The last photo from Germany was taken in 1941. The album picks up again in 1946 in Great Britain. While leafing through it, Sara Davidmann noticed something: “Looking through the photo-album I realised that many of these people in the early photographs did not reappear in the photographs taken after World War II. And I began to search for traces of their lives.”

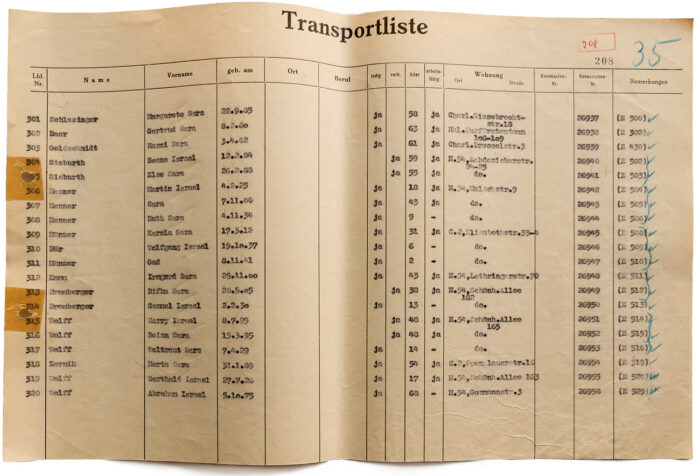

Her research brought her to the Arolsen Archives. She spent two days in the archive in Bad Arolsen, photographing documents that provided information about the fate of her family. They included transport notices showing that her great-aunt Marta was sent to Auschwitz and her great-grandmother Dorothea to Theresienstadt. Although she was already familiar with most of these documents and had looked at them on her computer many times, she was surprised by how moving it was to see the original papers relating to her family.

»To hold these papers marked by damage, to see the folds, rips, braille-like typewriter indentations, the signatures and handwritten ticks next to people’s names, and to know that these papers had been touched by the hands of others at the time when they were written—I could not have imagined the effect it would have on me.«

Sara Davidmann

Her father Manfred and his sister Susi – 14 and 17 at that time – survived the Holocaust by escaping from Nazi Berlin on the Kindertransport, arriving in Britain in 1939. A few days after the November pogroms, influential Jews began to arrange for children to be taken in temporarily; the strict entry regulations were not eased for adults. Over 10,000 Jewish children from the German Reich and other threatened countries were allowed to travel to Great Britain, in groups by train and ship. They were housed in their new country either with relatives or, more often, with foster families and in care homes. Many of them never saw their parents again. The children were often the only members of their family to survive the Holocaust.

Painful memories

Sara Davidmann’s father was never able to talk about his experiences growing up as a young Jewish boy in Nazi Berlin: “The traumatic events that occurred before he was evacuated, the family members who were murdered, or his evacuation—these all formed a chapter of his life that was too painful to revisit and so I was oblivious to my father’s experiences—and grew up knowing very little about the German Jewish side of my family—until long after my father’s death.”

Sara’s father Manfred and her aunt Susi, 1934 © Sara Davidmann

Sara Davidmann’s book “Mischling 1″ and the accompanying exhibition were not the artist’s first attempts to process her family history. Her project “Ken. To be destroyed” (2016) tells the story of her uncle Ken, who was transgender and only able to live as a woman in private at home. Ken’s wife Hazel wrote letters to her sister Audrey (Sara Davidmann’s mother) in the 1950s and 1960s which recounted the very intimate story of the unusual couple.

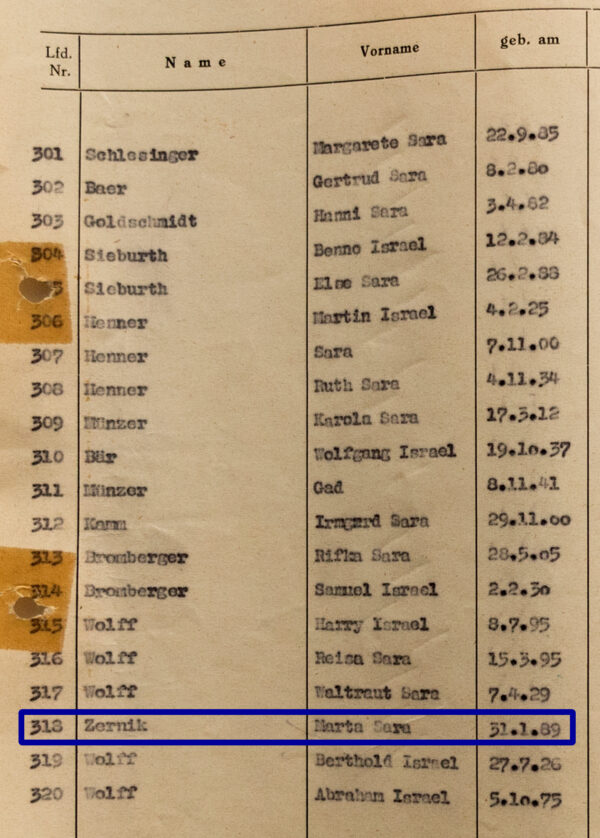

On the transport papers for Sara Davidmann’s great-grandmother Dorothea and great-aunt Marta, the name “Sara” is listed as their middle name. From 1938, the “Law on the Alteration of Names” required all German Jews whose names were not immediately identifiable as Jewish to adopt an additional name. For men, the name was “Israel,” for women it was “Sara”—the name Sara Davidmann’s parents would later give to her.

The last document

»The image shows the transportation document in connection with my great aunt Marta’s deportation to Auschwitz. Marta’s married name was Zernik. She is number 318 on the list. There are no further records for Marta after this document—this is the last record in connection with her life.

Through my research, and with the help of the Wiener Library in London and the Arolsen Archives in Germany, over 130 pages of Nazi and official documents were uncovered. These revealed that family members were deported to, and murdered, in concentration camps at Auschwitz and Theresienstadt. Others survived by escaping to Shanghai, France and Israel, and by living hidden in Berlin with false documents.«

Sara Davidmann’s book “Mischling 1” and the exhibition “My name is Sara” include photos, newspaper clippings, documents, and what are known as photograms made with old strands of the artist’s hair—a link between the shaved heads of concentration camp prisoners and life in the present day.

This project was supported by a three-year Philip Leverhulme Prize from The Leverhulme Trust.