"But I live!"

The fact that she survived still never ceases to amaze Emmie Arbel. When she was 5 years old, the Nazis tore her away from the life she knew and deported her to the Westerbork, Ravensbrück, and Bergen-Belsen camps. She was seven and a half when she was liberated and had to start a new life as an orphan. She is currently working on a graphic novel with artist Barbara Yelin.

Their collaboration is part of a research project titled Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education, which is led by the Canadian University of Victoria and involves a large number of international partners. The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Three different graphic novels are currently being created as part of the project.

In this interview, Emmie Arbel, Barbara Yelin, and project manager Charlotte Schallié talk about the process that went into the making of one of the books.

What does this project mean to you?

Emmie Arbel: This project makes it possible to reach as many children and young people as possible, because they don’t like to read books, but comics they like. It can help teachers (who also sometimes don’t know so much) how to talk about it with the children

Barbara Yelin: I feel that narrating Emmie Arbel’s memories is tremendously important and a huge responsibility at the same time. Her story made a profound impression on me, and even though it’s not all that long when you compare the number of pages with the length of my previous books, it has occupied my thoughts again and again over the past year.

Charlotte Schallié: For me, the personal encounters between the survivors and the artists are of central importance. The creative process produces intimacy, but it creates distance at the same time through the alienation effects achieved by the drawings. This contrast gives rise to tension that can be very productive for remembrance work. Because the language of pictures can be used to depict experiences that are no longer accessible to a person’s memory. In Barbara Yelin’s graphic novel, this can be seen in the way Emmie’s non-memories in particular – the blanks in her past – take on an incredibly powerful and impressive presence.

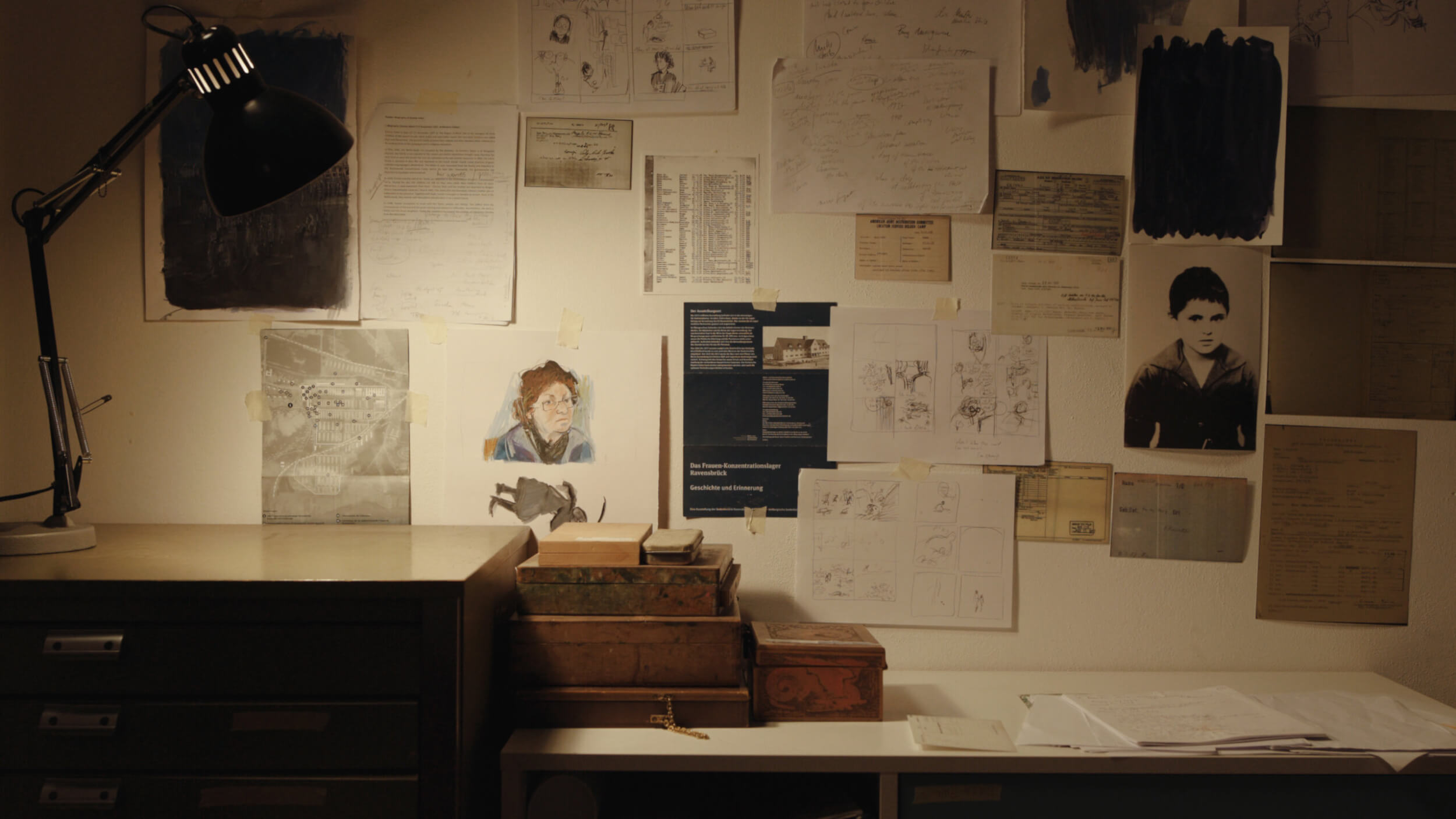

Photo material from Emmie´s childhood. Copyright Martin Friedrich

Sketches from the graphic novel. Copyright Martin Friedrich

Is it really possible to tell Emmie Arbel’s story?

Barbara Yelin: I tell Emmie Arbel’s story entirely in her own words. She has an extremely strong voice which I haven’t changed in any way, all I’ve done is to make a selection. The pictures are an accompaniment to her words. Some of the things she described are very distressing, and when I tried to draw them, I found that there were things I couldn’t show in detail because it would be unbearable to look at them.

When that was the case, I tried to depict fragments that show you what’s happening but don’t distort the events that took place. And I always interwove the memories with Emmie Arbel’s present, i.e. the moment of telling. Because it’s very much the contrast inherent in looking back from today’s perspective that makes the enormity of what she experienced and suffered in the Holocaust particularly affecting.

Is the graphic novel a form that is particularly well suited to telling this story?

Barbara Yelin: Generally speaking, comics and graphic novels are a narrative format that is very good at engaging readers. Reading a work that combines pictures, dialogue, narrative texts, and informational texts that have to be linked together in readers’ minds requires them to make an active contribution to the process. Not only does the act of reading get the reader acquainted with the story, at best, it is also has an unsettling effect that reverberates in the reader and prompts him or her to embark on a process of inner reflection and explore new questions.

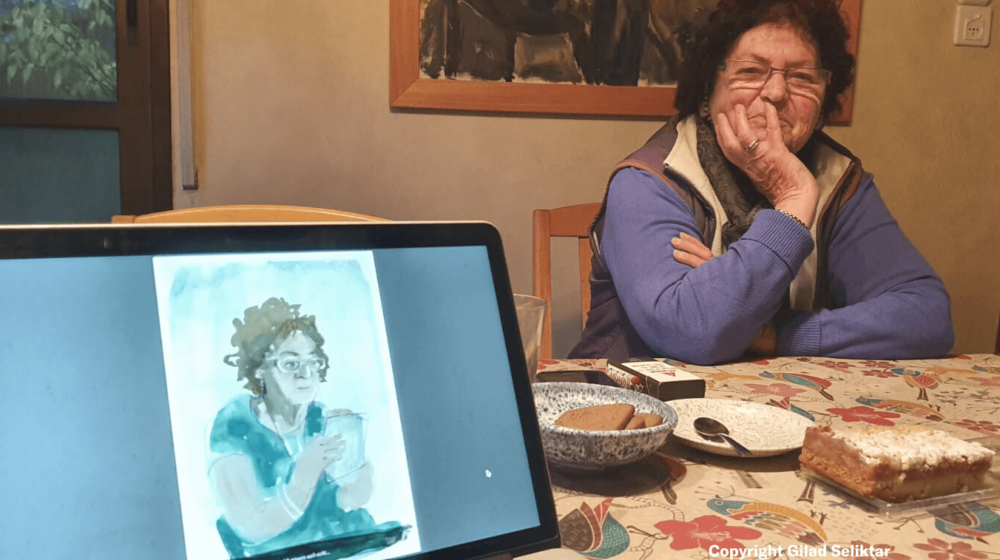

Illustrator Barbara Yelin visited Emmie Arbel in Israel. Copyright Gilad Seliktar

Illustrator Barbara Yelin visited Emmie Arbel in Israel. Copyright Gilad Seliktar

You met in person for the book, but Emmie Arbel can’t remember some of the things she experienced. How did you manage to fill in the gaps?

Barbara Yelin: I read up on Emmie’s life story, of course, in as far as it has been recorded, and I also read as much as I could about the places and historical events that are associated with it. But my meetings with Emmie Arbel in person were crucial. We spent a few days talking to each other about her memories. We discussed her childhood memories, her memories of deportation, managing to survive in three concentration camps, liberation, and the post-war period, and we also talked about her life up until the present.

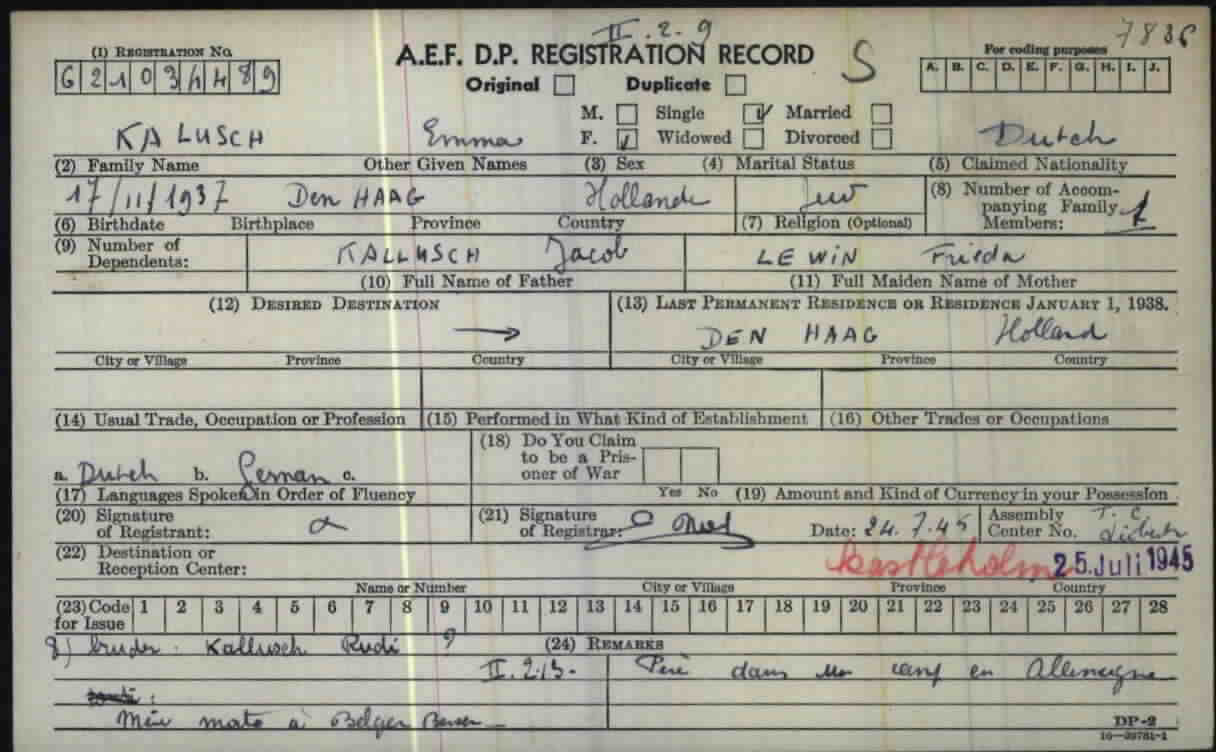

I then did further research, using what she told me as the starting point. I searched the archives of the Ravensbrück Memorial, for example, and read the memoirs of other survivors, including the memoirs written by her eldest brother, Menachem Kallus. Documents held in the Arolsen Archives were very important too, especially for those episodes that Emmie Arbel has no memory of or only remembers in part. The work done by the research assistants who provide advice and support for the project at various institutes was also a great help. In my case, I received invaluable support from the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich.

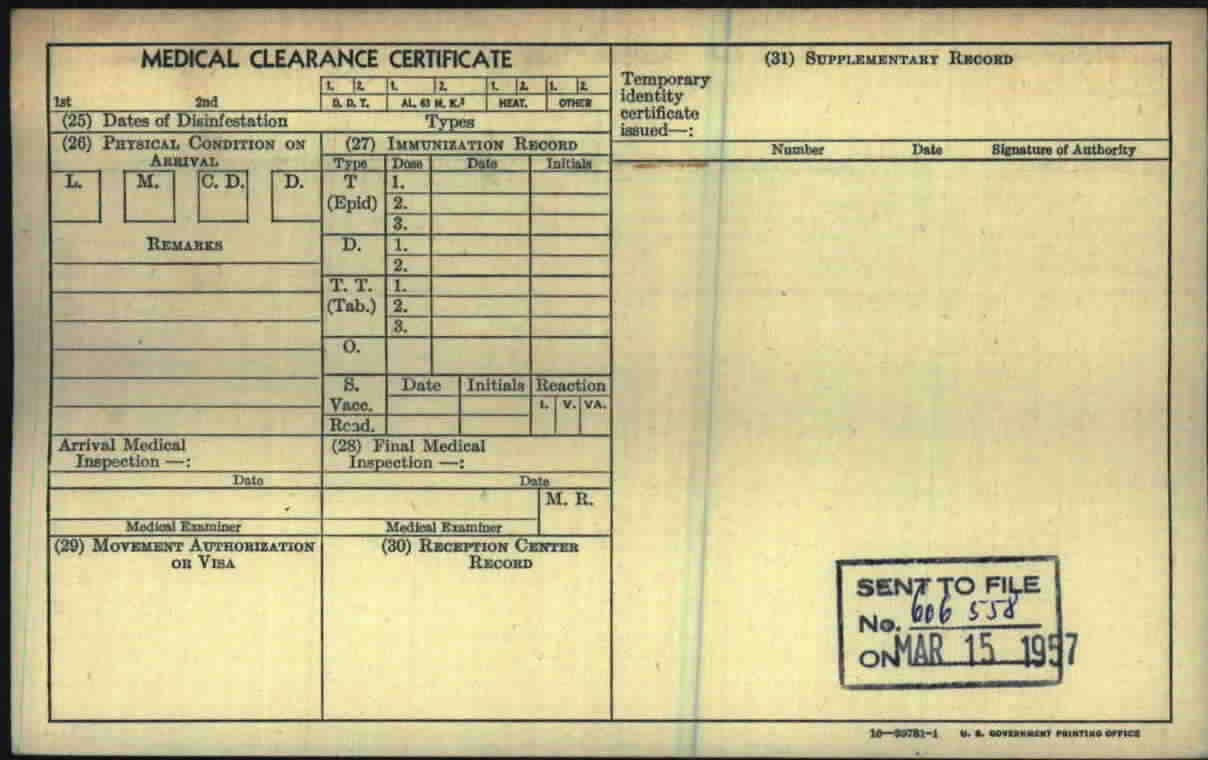

Emmie’s DP-2 card issued by the Allies after the end of the war to register Displaced Persons.

How do you manage to depict experiences that Emmie Arbel has no memory of?

Barbara Yelin: I think using drawings to create a sequential narrative can show two things particularly well. Emmie Arbel’s early memories are pictures, as she herself puts it. And I can draw those pictures. Black panels are a means of visualizing traumatic episodes. And another important aspect is that there are no pictorial references. There is no photographic material from Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. The few exceptions are photographs taken from the perspective of the perpetrators.

So what we are actually doing together is creating pictures that have never existed up until now – using Emmie’s memories, in dialog with her, using the research material as the basis, and my drawings.

Copyright Martin Friedrich

What’s it like for you, Emmie, to see your own story drawn in pictures?

Emmie Arbel: When I heard for the first time that it will be in comics, I didn’t like the idea, but as I thought about it more, I began to understand and now I think that it’s a great and creative project.

What would you like to achieve with this project?

Emmie Arbel: The main thing for me is the importance that those terrible years will not be forgotten, to prevent it from happening again, because if it happened in Germany, it can happen everywhere in the world. If it will convince many children – who will be the adults of the future – then I know that I DID IT! (at least I tried)….

Charlotte Schallié: Once they’ve been published, the graphic novels will be used in schools. All the teaching materials and supplementary materials that have been produced to go with the novels will be freely available to teachers, Holocaust educators, and researchers, and we would like to give presentations and workshops about the process of working together and provide a best practice guide as well.

Many thanks to Emmie Arbel, Barbara Yelin, and Charlotte Schallié for giving us this interview. The three graphic novels will be published in spring 2022 by publishers C.H. Beck and New Jewish Press.