Digital memorial to the victims of Nazism: AI helps reconstruct individual fates

The National Socialists used lists in their perverse drive to perfect their system of persecution. Today, their meticulous records provide valuable additional information about the fates of individuals. Over a million such documents are stored in the Arolsen Archives. Whose name is on which list? The Arolsen Archives recently began using artificial intelligence to extract information about victims of Nazi persecution automatically from these lists and link it with data contained in other documents. Each detail helps to reconstruct the path a person’s life took and the persecution they endured. The comprehensive online archive, which can already be searched by people all over the world, continues to grow at the same time.

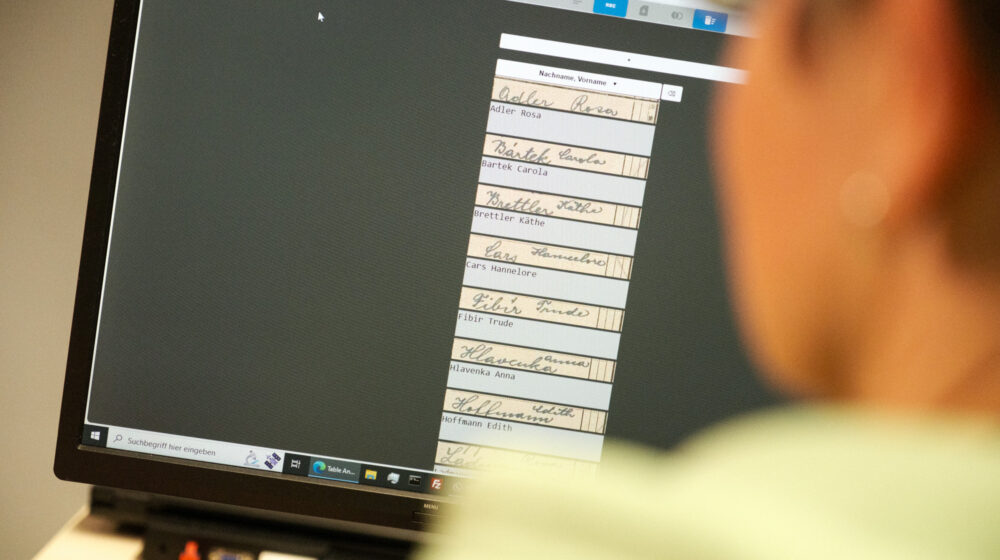

Martina Steiner-Güde opens a new document on her PC. It is a scan of a list of detainees held in the Dutch transit camp Westerbork. About 7,000 lists from the Westerbork camp are stored in the Arolsen Archives. The first page contains the names of around 50 people, their dates of birth, and where they were born. Most of the information on the document is typewritten, but a few handwritten notes were added later. Stains, holes, tears, and creases obscure some of the letters. Other pieces of information are difficult to read because the paper has grown yellow with age. None of this presents a problem for Martina, who works at the Arolsen Archives. By consulting the database and using the knowledge she has built up over the years, she could soon fill in the gaps.

Martina Steiner-Güde at her computer, checking the quality of a machine-indexed list from a concentration camp

Average processing times of half an hour per page are a thing of the past

Just one year ago, her next job would have been to start the process of deciphering and typing out the information on the list – name by name, place by place, and date by date. “It takes about half an hour per page, depending on the amount of data,” she says. Today, she can take the list and generate a structured, computer-readable – i.e. indexed – file with just a few clicks of the mouse. “This is a huge leap forward and saves us loads of time. Now I can concentrate on checking the quality. The program does the rest,” she explains. It saves her around a third of the time it used to take. And that number is set to rise even higher.

Thanks to AI, it is now possible to automatically extract important information about victims of Nazi persecution from multi-page lists with just a few clicks of the mouse.

Optical character recognition is not enough

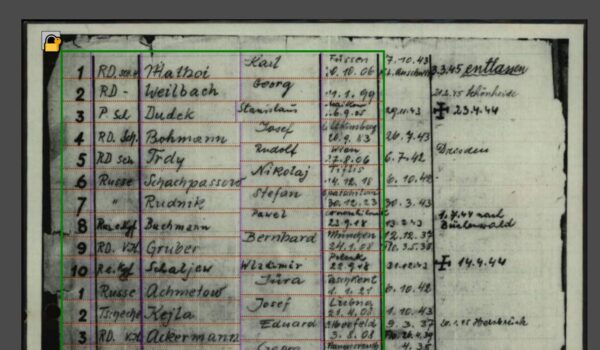

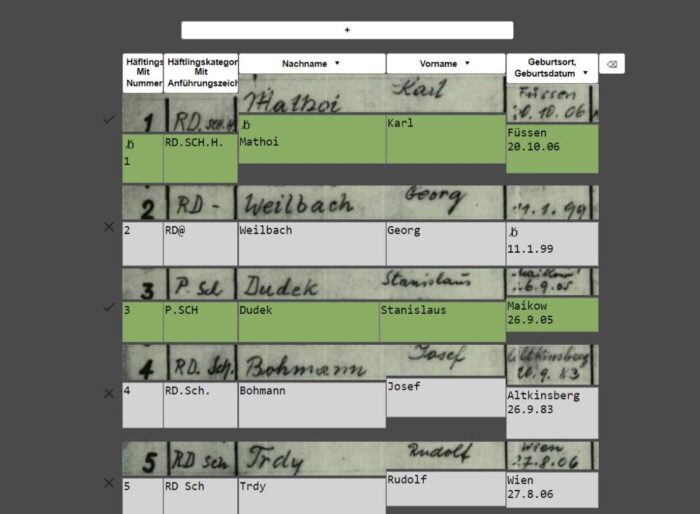

The program that does all this is an AI-controlled “OCR system.” OCR stands for Optical Character Recognition. These systems work by converting images to text. The information contained in the scanned images of the documents needs to be made available in text form so users can find more and more information in the online archive of the Arolsen Archives. “Traditional OCR systems generally achieve accuracy rates of around 80 percent. But we need over 99 percent, otherwise the results are no good to us,” explains Michael Hoffmann, Head of the Data Integration Unit at the Arolsen Archives. “Only then can we assign the ‘right’ personal details to a certain name, e.g. only then can we automatically collect all the information about Leonard Cohen, born in Lodz on 09.10.1903, and bring it all together.”

The goal: an online archive that can tell millions of stories

The Arolsen Archives began making their holdings available online in 2019. The latest technology for capturing the data contained in lists is helping the online database to grow fast and taking it to a new level. “We don’t just want to document the names, we want to find out about people’s life stories and make them available to the public. AI can help us achieve this,” explains Giora Zwilling, Head of Digital Transformation & Archives. “In order for it to work, a lot of different information from different documents needs to be linked together. Afterwards, people who research online will no longer be shown a multitude of individual documents, but a kind of dossier containing all the available information. That would be a quantum leap.”

» We have over a million lists. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my time at the Arolsen Archives, it’s to be in awe of big numbers. «

Michael Hoffmann, Head of the Data Integration Unit

Digitization and Indexing staff work hand in hand

The Data Integration Unit and the Indexing Team have put in a huge amount of work and are now well on the way to achieving this goal. “We want to be able to assign information to a specific person. Even a small mix-up in the numbers that make up the date of birth – a zero being mistaken for an eight, for example – will falsify the results. The documents are 70 or 80 years old, most of them were scanned in the 1990s. That means the quality is not particularly good, and as a result, the error rate would be far too high if we used conventional OCR,” explains Michael Hoffmann, describing the difficulties faced in the past in greater detail. “Rescanning the documents might improve the quality of the images, but in terms of personnel and technology, it would be a huge job.”

AI fills the gaps in the data

In mid 2022, the 13 colleagues in the Indexing Team, led by Claudia Kuncendorfs, began training an AI model to improve the quality of the data read out with OCR. “The data is checked for plausibility using a matching process and the results are compared with existing data,” she explains. This means that the AI adds any data that is missing to fill in information gaps.

One particular difficulty encountered with conventional OCR methods was their inability to automatically read lists in table form. And asking volunteers to process this type of list in the context of our crowdsourcing project #everynamecounts did not work well either. “Spending half an hour or more on a single document is too much of a challenge for volunteers, so we’re really pleased that the project still delivered a solution,” explains Michael Hoffmann.

System learns more every day

Software developer Thomas Werkmeister became aware of the Arolsen Archives in 2021 through #everynamecounts – and soon offered to develop an AI solution for reading table structures. Funding for the project came from a federal program. Now, the AI solution is able to do even more than that. It learns more and more every day. The system can now recognize handwritten text too, as the software programmer continues to develop the AI solution.

Reading old handwriting

Old handwriting is often almost impossible to decipher, even for humans. The Arolsen Archives Indexing Team are teaching the AI solution how to do it.

Linking data to reveal life stories

Martina has just typed in an @ sign in front of an entry to tell the AI that “Amschwitz” is obviously a typing error in the original document, not a recognition error, and that it should therefore not be included in the data used for training the model. “At the moment, we’re working on the assumption that our archives contain information on 17.5 million individuals. Our core collections include one million lists, each of which contains 12 to 15 names, and we also have 30 million documents about individual people. What we aim to do with AI is to assign various documents to specific individuals using ‘person matching’,” says Michael Hoffmann. “By2017, we had indexed 8 million personal data; we should be able to reach the 38 million mark before long.” In the long term, the team will use new technologies to create visual links to all the data can be found on a specific person. So-called knowledge graphs can then be used to visualize deportation routes or escape routes, making the suffering imposed on victims of Nazi persecution even more tangible.