Dina Babbitt: Painting her way out of hell

In Auschwitz, the young artist Dina Babbitt had to paint portraits of other inmates – Romani people who were to serve as models for an absurd “racial inferiority” project devised by SS doctor Josef Mengele. Dina saved her own and her mother’s life with these paintings and became a well-known cartoonist after the war. Up until her death in 2009, she fought for the restitution of the Auschwitz portraits. Today, Dina’s daughters continue her quest for justice and remembrance.

When she was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, Dina Babbitt (born Gottliebova) was fascinated by Walt Disney’s first animated feature film: “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” which hit Prague cinemas in 1938/1939. In Germany, Jews had just been forbidden access to cultural institutions. German-occupied Czechoslovakia was to follow the restrictions soon, too. Dina, who was born Jewish, went to the movies anyway.

“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” released in 1937, was the world’s first full-length traditionally animated feature film. (Photo: colaimages)

Remembering “Snow White” would save Dina’s life

Dina was so impressed by the film’s artistic design and technical sophistication that she saw it many times, even in 1941, when it became very dangerous as Jews were required to identify themselves by wearing a yellow star in public at all times. The film was a great hit in Prague and all over Europe. Everyone knew it, and Dina’s detailed memory of the scenes and animation styles would help her survive the Holocaust…

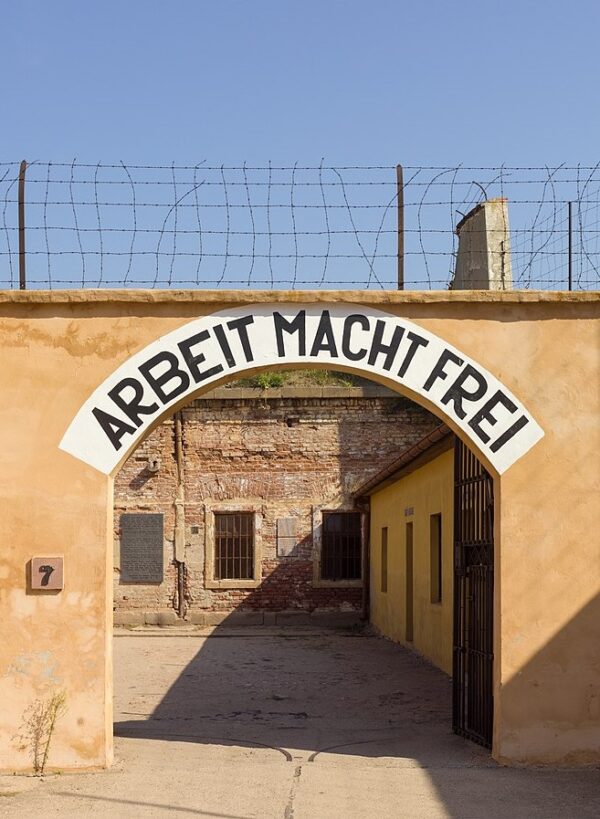

From Theresienstadt ghetto to Auschwitz

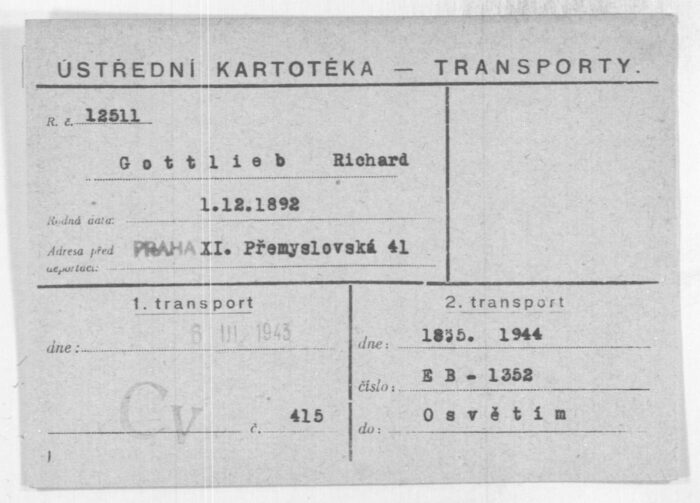

The Gestapo arrested Annemarie Dina Gottlieb and her mother Jana in their home town near Prague on January 21, 1942 – Dina’s 19th birthday. They were imprisoned in the Theresienstadt ghetto for over 18 months. Dina’s father arrived in the ghetto in March 1943. On September 6, 1943, the SS transported Dina, her mother, and thousands of other Theresienstadt inmates to Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland.

Dina met a friend in the camp

The SS had established the “Theresienstadt family camp” in Auschwitz to assemble, and ultimately kill, Jewish inmates from the Czech ghetto. Dina wound up in one of the camp’s children’s barracks. She knew Fredy Hirsch, the supervisor of the children’s block, from her hometown and her time in Prague, where he was a Zionist youth movement leader. Fredy helped thousands of Jewish children in Theresienstadt and in Auschwitz. Dina and 12 other Auschwitz survivors told his story in the moving documentary “Heaven in Auschwitz”:

A “Snow White” mural for the children of Auschwitz

Fredy knew that Dina was a talented artist, and he asked her to paint a mural on a wall of one of the children’s barracks to cheer the kids up. Dina feared punishment from the SS, but she started painting anyway – a colorful mountain landscape. When the children came to watch, she asked them what else they wanted to have in the mural. They wished for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” and Dina painted a vivid scene that she remembered from the movie. A couple of days later, an SS officer actually sought out Dina. He asked her if she had painted the mural, and she admitted to being the artist.

»I was sure: this is it. They will shoot me, I am not going to survive.«

Dina Babbitt, USHMM oral history interview, 2009

Mengele deployed Dina as a portrait painter

However, the SS officer brought Dina to another “family camp,” where Romani and Sinti people were being held. There, the Auschwitz “Angel of Death,” SS doctor Josef Mengele, was working on a perfidious photo portrait series of Romani people. He tried to classify their “racial features” in order to demonstrate the Romani’s inferiority to “Aryans.” However, Mengele found that the photos did not capture the skin tone of the inmates to his satisfaction. He asked Dina if she could paint portraits, too, and do a better job with the skin tone. “I can try,” said Dina.

SS doctor Josef Mengele set up his laboratory in the “Gypsy family camp” and abused inmates in pursuit of his research interests – some were “only” photographed, while others were subjected to lethal experiments. (Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum)

But the “job” did not start immediately. Dina was brought back to her barrack, and she did not hear from Mengele for months. Then, rumors started that all the people who had been on the first Theresienstadt-Auschwitz transport – which included Dina and her mother – would soon be killed in the gas chambers. The official line was that they were to be transported to a work camp, but few people believed that. Dina saw Mengele again, and he asked her if she could do the portraits now. Boldly, Dina said she would, but only if her mother could stay with her. Mengele agreed and put Dina and her mother on a list of people who would not be put on the transport.

Painting slowly, Dina saved lives

Over the next year, Dina painted the portraits of twelve Romani people. Dr. Mengele often pointed out features to her that he wanted to be emphasized because they were different from the features of “Aryan” people – eye colors, ear shapes, hairlines. Dina, on the other hand, tried to capture the suffering and desperation in their eyes. She formed friendships with some of her “models,” shared her bread with them, and painted slowly – because the longer it took her to finish the portraits, the longer were her chances of survival, and the same held true for the model and her mother.

Gallery: Dina Babbitt’s Auschwitz portraits

-

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum -

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum -

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum -

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum -

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum -

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum -

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Photo: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

New life in Paris after the war

Shortly before Auschwitz was liberated, the SS deported Dina and Jana to the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp in Germany. From there, they were sent on a so-called death march to a sub-camp, where they were liberated on May 5, 1945. Jana and Dina returned to Prague and lived there until September 1946. After that, they moved to Paris.

Animation career in the U.S.

In France, Dina met the American animator Art Babbitt, who had created some of the “Snow White” characters. They married and moved to California, where they went on to have two daughters. Dina worked for famous cartoon studios and developed well-known comic characters like Daffy Duck, Speedy Gonzales, or Tweety. In 1954, Dina’s mother Jana also moved to California.

The portraits resurfaced 30 years later

In 1973, Dina received a letter from the State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau: Seven of the portraits had been found and attributed to her. Dina travelled to Poland to receive them and take them back home – which she wasn’t allowed to do. Ever since then and right on uptil to her death in 2009, Dina fought to get her works back. Today, her daughters and grandchildren continue her quest.

»My sister and I have not stopped fighting, because it is morally correct. Many other artists who support us say this, too: You enslave people by retaining their art. My mother was devastated when she died without getting ahold of these portraits again, and of the people in them.«

Karin Babbitt, comedian, actor and screenwriter

Auschwitz Museum wants to preserve the images on site

In 2001, the International Auschwitz Council issued a statement declaring that, as material documenting Nazi crimes against humanity, the paintings belong at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim. Representatives of the museum are convinced that objects and documents found in the area of the liberated camp should be protected for further generations. The International Council of Remembrance of Extermination of the Romes in Poland has expressed similar views.