“Drawing on history to develop options for a peaceful future“

Today marks the second anniversary of the start of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. For 730 days now, Ukrainians have been living with bombs, destruction, flight, death and grief. How are they coping? What gives them hope? We asked Angela Beljak about this. She is a Ukrainian project partner for #StolenMemory, conducts interviews with refugees in Germany as part of a documentation project, is studying social psychology in Kyiv, was the coordinator of Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste (Action Reconciliation Service for Peace) there for many years and knows what effects the trauma of war can have.

Ms. Beljak, this war of aggression has been going on for two years now. What is life like in Ukraine today?

On the one hand, life goes on as usual for us here in Kyiv. All the shops are open. We can buy all the groceries we need. Public transport is working. Children go to school, people go to work. On the other hand, war is a constant presence. There are air raids every day. As a result, new routines have developed. Wherever you are, you first have to find out where the nearest bunker or shelter is.

»At the moment, there are so many people who are not doing very well at all, but we can support each other.«

Angela Beljak

How are you coping personally?

I’m okay in the sense that we’re still alive. Our apartment and the house are still standing. Fortunately, we’ve been spared physically. Psychologically, everything that’s happening here is very distressing and extremely hard to endure. But you have to stay strong for the children. My children look to me and I have to show them what we can do to stop this terrible situation from driving us to despair.

Fleeing to Romania and returning

When the war started, you fled with your family to Romania, but then decided to come back again. Why?

At the beginning, we didn’t know what was going to happen. The bombs were falling. There was no time to think about whether or not to stay. I had to save my children. There was no alternative but to flee. We weren’t simply leaving the country, we were fleeing it. We stood at the border for over twelve hours because so many people wanted to leave the country at once. But not all of them were able to flee. Many people in need of help were left behind, particularly the elderly. We realized then that these people need our support. That’s why we came back. We wanted to provide physical and psychological support. I tried to organize aid campaigns in Ukraine, even while I was in Romania. If you are able to offer this support, this is also a strategy for preserving your own mental health. It’s a tool, a survival strategy: Doing something for others, feeling the bond. You give a lot and also get a lot in return. Talking about insecurities, fears, mourning the loss of everyday life – that, too, is very important right now. At the moment, there are so many people who are not doing very well at all, but we can support each other. That helps all of us. It’s also a form of resistance.

It’s particularly hard for children and young people to understand why entire villages are reduced to rubble like here in Novoselivka, Ukraine (Photo: Ales Uscinaw/Pexels).

Those Ukrainians who have fled and have not yet been able to return, how are they doing? What do you hear from the interviews that you’re conducting for the documentation project run by the Hagen Fernuni (Germany’s only state distance-learning university)?

The war is just as present for them. Most of them have husbands, fathers, brothers or other family members or friends at the front. Physically they’re in a safe place, but mentally they’re back in Ukraine. They watch the news, keep in direct contact, collect donations all the time, buy drones, do what they can for Ukraine. They feel a very strong connection to the country. However, the situation is changing. Many of the people I interviewed in Hagen come from the eastern regions. Their hopes of returning are fading. Many of them will have no homes to go back to. Young women with children who have just started school, in particular, are now adjusting to a permanent life in Germany, and to the very different school system.

Your work as coordinator of Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste projects in Ukraine and Belarus has ceased for now…

Yes, unfortunately this work has had to be put on hold. I’ve therefore decided to seek a new challenge and am doing a master’s degree in social psychology. I’m studying how people interact with each other in which social context, how they influence each other and how they make which decisions in which situations. This fits in well with my previous work and the documentation project in Hagen.

You’ve previously organized voluntary programs and meetings in which the participants primarily deal with the crimes of National Socialism. Through these, you know many Ukrainian Holocaust survivors personally. How do they experience the current war?

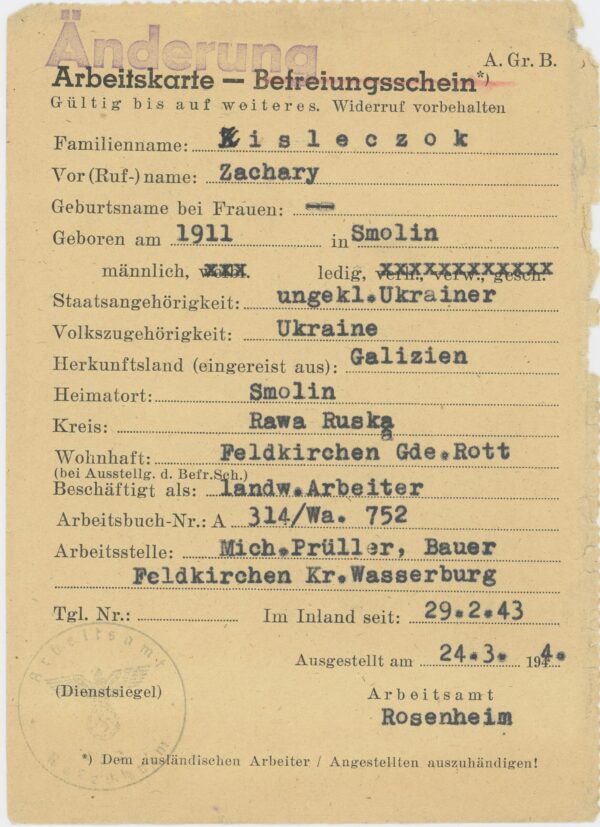

Traumas are coming back. The fear of bombing, childhood memories of the terrible hunger, the fear of the planes, all of that is resurfacing. Many of them have never come to terms with the experiences of that time. After the Second World War, no-one was allowed to talk about it, about forced labor, captivity, concentration camps. That left deep wounds that are now being opened up again. This shows how important it is now to talk about emotions, about fears. Unlike back then, there are many offers from psychologists today. You can sign up online for discussion groups, and international initiatives also offer projects.

A look at the history books shows parallels

Does it help younger people to talk to the older generation about their experience of war?

Yes, young people are now very interested in learning about the survival strategies of those persecuted by the Nazis. Many survivors say that it’s important to concentrate on everyday life, to actively shape it with banalities such as fetching water, heating the apartment, all of which helped them to survive the terrible time emotionally. Many young people also look to history for answers to the question of why we were attacked, why so many Russians want to kill us. After all, we didn’t do anything to them. What we’re experiencing now is closely linked to history, to what happened in the Nazi era, during the Second World War. A look at the history books shows parallels: The war of extermination, the concept of concentration camps, methods of shooting people.

With #StolenMemory, the Arolsen Archives are also attempting to return the personal items of victims of Nazi persecution to their surviving family members in Ukraine. The personal effects of 60 people from Ukraine are stored in Bad Arolsen. Are the people there even able to think about something like this today?

When family members disappear in war, it’s a traumatic experience that overshadows entire generations. When you don’t know what happened to a person, a loved one, this important part of me and my family, my past. Returned items and keepsakes can close these gaps. They are symbols, a sign that this person has found a place within the family again. The current war is tearing the very same gaps. You don’t hear anything from soldiers or civilians for a long time, you don’t know what has happened to them. It’s incredibly difficult to understand and endure something like this. That’s why this project is so important and I think it’s good that the accompanying exhibition is now touring Poland in the Ukrainian language and visiting places where many Ukrainian families have found refuge. It was originally planned for the exhibition to visit Ukraine as well. The war has put a stop to that. That’s why I’m now looking forward to another joint project even more. On March 13, we will be meeting with young people from Germany, Poland and Ukraine for a #StolenMemory seminar in Oświęcim (Auschwitz). The project is being funded through the partnership with the DPJW (German-Polish Youth Office), and eight young people from each country will attend. I’ll be accompanying the eight pupils from a school in Kyiv.

#StolenMemory exhibition visits Zamość in Poland

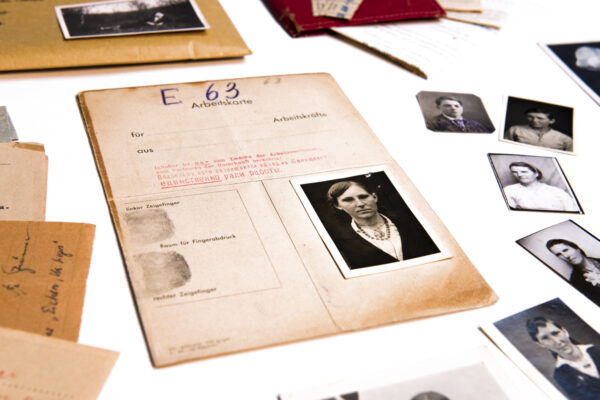

Personal effects of 60 people who came from areas that now belong to Ukraine are stored at the Arolsen Archives. At #StolenMemory, we are, for example, searching for relatives of Maria Holowko, born on 29 October 1926 in Posiolok, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast.

How important do you think projects like these are?

Exchange projects are very important. They give us a lot of hope for the future. The more we run projects like these, the greater the chance we have for a peaceful future. Personal discussions help us to break down our own stereotypes and really learn from each other. Young people from Germany or Poland experience first-hand how terrible war is, how important the people around you are, how important social contacts are. A human life has the highest value, that’s what the project is about. The Arolsen Archives play an important role here: If we don’t talk about our past and know nothing about it, there will always be war. History will just be replaced by myths. That’s exactly what’s happening again today. This makes it all the more important for the Arolsen Archives to preserve original documents and make them accessible to everyone It’s really great that so much is available online today, helping people around the world to reconstruct their family history. Working together with pupils, drawing on history to develop options for our future, this is a project I’m looking forward to. If the younger generation manages to learn how we can live in harmony with each other, then we have hope for a peaceful future.

Our Ukraine aid network

The Arolsen Archives are part of an aid network for survivors of Nazi persecution in Ukraine. Since the war of aggression started, the aid network has not only provided unbureaucratic and effective support to survivors of Nazi persecution in Ukraine, but also to their families and to colleagues affected by the war. Some 46 initiatives, foundations, places of remembrance and memorial sites in Germany are taking part. Together we are calling for donations to help Holocaust survivors and their families.