“Things shouldn’t have to happen to you personally in order for you to care!”

Our project “Every Name Counts” relies on volunteers – more than 8000 of them now transcribe the personal data of Nazi persecutees from documents in the Arolsen Archives in their spare time in order to make them searchable online. Even entering just one name makes a valuable contribution to the fight against oblivion.

But some of our volunteers do even more. They use their language skills and their local knowledge to correct the names of people and places. They carry out research and share additional knowledge or help each other to decipher handwriting that it difficult to read.

Fernando Gouveia from Portugal is one of them. Working on “Every name counts” gave him the idea of uploading documents from the Arolsen Archives to “Wiki-Commons.” He carries out research and uses the information in the documents to correct inaccuracies in the online encyclopedia. We asked him what motivates him.

When did you first start volunteering for the “everynamecounts” project?

I started working on the project on 15 May.

How did you find out about the project?

I’ve been involved in Zooniverse since 2019, and I receive updates on new projects. When I read about this one, I knew I had to be in it.

You belong to the group of volunteers who work most intensively on the project. But you write that you have no personal (family) connection to the topic. What motivates you to invest so much of your time?

Yes, I have no direct connection to the topic or to WW2 in general: my country (Portugal) was not involved in the war, no family member was involved either. I also do not belong to any of the groups typically targeted by the Nazis. But things should not have to happen to you, personally, or to your group (whatever that might be), in order for you to care about them.

History in general interests me, and WW2 — with its unimaginable, industrial scale of human suffering, but also bold examples of defiance and courage, of commitment and self-sacrifice — has been of personal interest to me for decades.

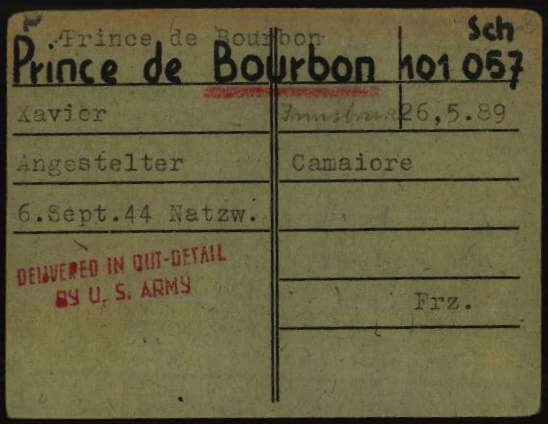

The card from the registry office card file of Dachau concentration camp of Prince Xavier de Bourbon-Parma gave Fernando Gouveia the idea to link documents at Wikipedia.

You do much more than we ask for in the project. For example, you have created a detailed table in which the abbreviations of the religious communities are broken down. You also research additional information about the people on the documents, update Wikipedia articles, and post documents on Wikipedia. Where did you get these ideas?

From my previous experience with Zooniverse I knew that hashtags can be useful. I started tagging nationalities when a volunteer said he was looking for Spanish prisoners who might have been in the same camp as his grandfather. Then came religions; the creation of a systematic list was a way of organizing my own notes and, if possible, prompting others to do the same.

Searching for further information about the prisoners started as a practical thing: sometimes you have doubts about the handwriting, or there’s conflicting information, and you want to be sure.

The thing with Wikipedia started when a volunteer found the card of Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma and linked his Wikipedia page: they quoted a biography titled “Dachau prisoner nr. 156270” — but the card proved his number was 101057! I had to correct the record, so I asked the research team if I could upload the image to Wikimedia. That’s how it started.

What is special for you about the project?

The fact that it treats victims as individuals. Often, even though we do it inadvertently, we deal with them in bulk: “This many millions died; this many were deported.”

Is there a document that you have handled that you remember especially, one that has touched you in a special way?

There are many more harrowing stories, but maybe Adolf Lande is someone I would like to mention here: he was a Jewish Austrian who was an international legal expert on drugs. His Wikipedia bio has only 4 sentences and includes nothing at all about his imprisonment. Even a book that mentions him only states (misleadingly) that he “fled across Europe to America after the Anschluss”, as if Dachau and Buchenwald never happened. He spent 3 months in each camp, but apparently the people that worked with him later were unaware of that fact. My guess is that he avoided the subject. He probably wished he really had left right after the Anschluss.

Is there something you wish for from us?

Carry on! An improved searching tool would be great.