Off to a new world: the emigration of displaced persons

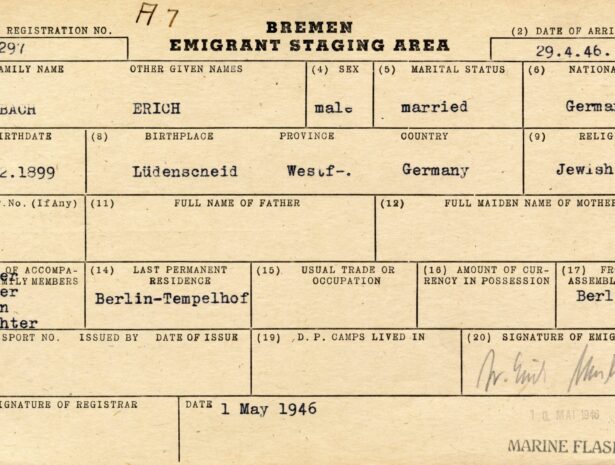

The volunteers now taking part in our #everynamecounts crowdsourcing initiative are digitizing a very special collection of documents. The “emigration card file” contains written records of the emigration of displaced persons (DPs) and others who wanted to leave Germany after WW II. Using the information contained in these documents, it is possible to retrace individual fates and the paths people took to emigrate to countries all over the world. Thanks to #everynamecounts, these documents will soon be online and searchable for anyone.

Around eleven million so-called displaced persons were in Germany at the end of the Second World War: liberated concentration camp prisoners, forced laborers, prisoners of war – in short, millions of people who were no longer living in their home countries because of Nazi persecution and deportation. Many of them were severely malnourished and in very bad health. The Allies and international aid organizations such as the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) did all they could to help the DPs and return them home.

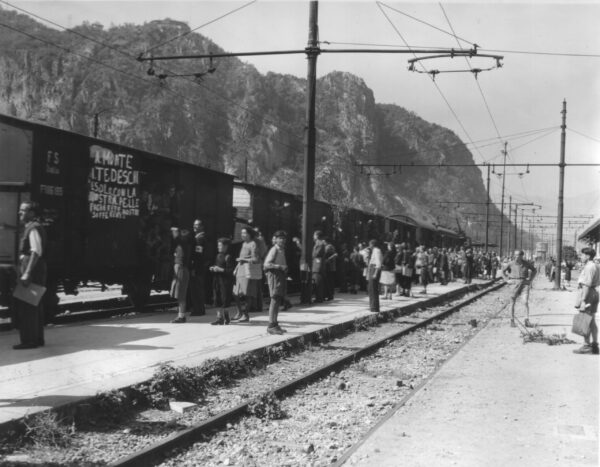

DPs arriving in Bolzano in August 1945: for millions of deported Nazi victims longing to return home, that dream came true shortly after their liberation.

Many DPs did not want to return to their home countries

One of the common goals the Allies formulated as early as February 1945 was the repatriation of all DPs to the countries they originally came from. By the end of 1945, they had managed to repatriate six million DPs quite quickly. But repatriation then came to a standstill. Fewer and fewer people wanted to return to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe – either because they did not want to live under Communism, or because their homeland no longer existed in its previous form, or because they feared further persecution if they returned. In addition, people from countries such as Hungary, Poland, and the Baltic States were traveling to Western Europe to escape from the Soviet sphere of influence for political reasons.

Returning home could be dangerous for people from Eastern Europe who were abducted by the Nazis. Photo: Arolsen Archives

Soviet prisoners of war and forced laborers were generally suspected of having collaborated with the Germans. They were often repatriated under duress and were faced with reprisals or arrest in their home country. Many of these people disappeared without trace after their return. Or they were imprisoned and put to work as forced laborers all over again, this time in the Soviet Union. In addition, a new group of DPs began to appear in 1946, as tens of thousands of Jews fled to the West to escape the ongoing pogroms in Eastern Europe.

» The great difficulty is that so many of these persons have no homes to which they may return. The immensity of the problem of displaced persons and refugees is almost beyond comprehension. «

US-Präsident Harry S. Truman, Dezember 1945

Care and resettlement of DPs – a Herculean task

While the Soviet Union refused to recognize the status “DP,” failed to set up provisions for the people in its occupation zone, and insisted on the repatriation of all those who had been deported by the Nazis, the Western Allies chose a different path. In February 1946, a UN resolution was passed stipulating that repatriation had to be voluntary. Permanent resettlement was to be made available as an alternative. The specially founded International Refugee Organization (IRO) set up an extensive aid program for the DPs and liaised with countries that were willing to accept them as immigrants.

The DP camps

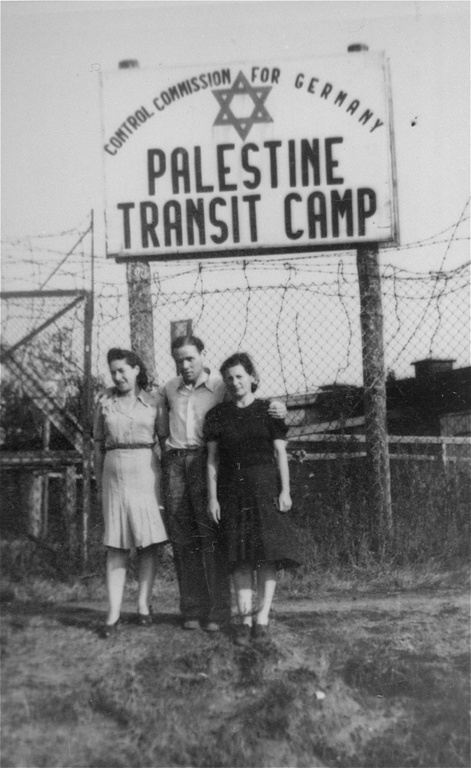

People lived in DP camps until they could emigrate. The IRO used various sites for this purpose, including barracks that had belonged to the Wehrmacht or the SS, former labor camps, and parts of former concentration camps. As well as accommodation, food, and health care, they also provided schools for children and retraining courses for adults. People of different nationalities were looked after in different camps. Separate Jewish DP camps were set up to protect Jews from antisemitism, which was widespread.

Hundreds of thousands emigrated

Harry Truman, the US President in office at the time, worked particularly hard for the admission of DPs, and by signing the “Displaced Persons Act” in 1948, in particular, he made it possible for hundreds of thousands of people to emigrate to the USA. Israel was the most important destination for Jewish DPs. But Canada, Australia, and the countries of South America were also very popular among those DPs who wanted to emigrate. In the DP camps, the IRO assisted them with the formalities of the emigration process and arranged preparatory courses and language lessons for the appropriate country of destination.

Preparation for emigration

Bremerhaven in Germany was one of the most important points of departure. People spent the final weeks before their emigration in staging centers in the nearby city of Bremen, such as Camp Grohn, where this film footage (Courtesy: USHMM / Julien Bryan) of DPs studying English was taken.

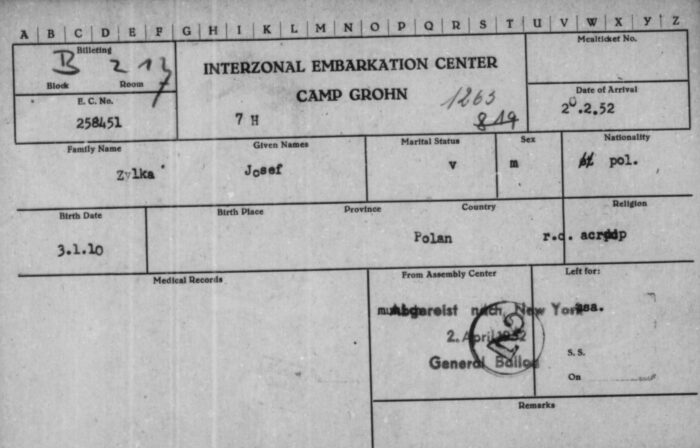

Józef Żyłka

…was one of the last survivors to emigrate to the USA in 1952. The Nazis had deported him from Poland in 1940 as a forced laborer. After the war, he was one of more than 500 DPs who helped build up the International Tracing Service (now the Arolsen Archives) . The photo shows him with his family just before their departure. They traveled on the US ship “General Ballou,” as recorded on his emigration card file.

„Ship to Freedom”

Most DPs left by ship; like in this film (Courtesy: USHMM / Julien Bryan) from October 1948: Over 800 people from eleven nations went aboard the General W. M. Black to New York.

The end of DP emigration

In 1951, the Allies transferred responsibility for the remaining DPs to the Federal Republic of Germany, which referred to them as “homeless foreigners” from then on, a clearly discriminatory term. The IRO called for the former DPs to be referred to as “refugees under the protection of the UN,” but the German government rejected this proposal. The IRO ceased operations on January 31, 1952. In Bremen, the Camp Lesum – now called Bremer Überseeheim – continued to serve as an “Auswanderer-Verschiffungslager” (emigrant shipping camp) for individual emigrants who were not emigrating under IRO programs. In addition to DPs, this group also included many other emigrants from all over Europe who were able to finance their emigration themselves.

» I stopped being a DP the day I obtained my American Citizenship. I am blessed with a wonderful life due to the strength and courage of my parents. I share my story with my children and grandchildren. I want them to know I was a displaced person. They need to know what that means, how it happened and how we survived. «

Barbara Garason was born in a DP camp and emigrated with her parents in 1949 (photo )