#everynamecounts as a school project

The Max-Windmüller-Gymnasium, a UNESCO associated school in Emden, Germany, called for people to join in #everynamecounts to mark Max Windmüller’s 101st birthday on 7 February, 2021. The “Keep the Memory Alive!” project group presented the memorial initiative at their school in a video conference. Participants were impressed by the Arolsen Archives project and found the experience of looking at individual fates of victims of Nazism deeply moving.

How does #everynamecounts work? Who can participate in the crowdsourcing project? Last Sunday, students at a school in Emden took on the role of ambassadors for #everynamecounts and set about recruiting new volunteers. The Max-Windmüller-Gymnasium in Emden is a UNESCO associated school named after resistance fighter Max Windmüller. To mark what would have been his 101st birthday, the school lent its support to the #everynamecounts memorial initiative of the Arolsen Archives. The activities were prepared by students in years 10 to 12 who are involved in the German-Israeli project group “Keep the Memory Alive!” They opened the video conference by introducing #everynamecounts. The memorial event was attended by teachers, parents, and about 40 students, the youngest of whom were in year 7.

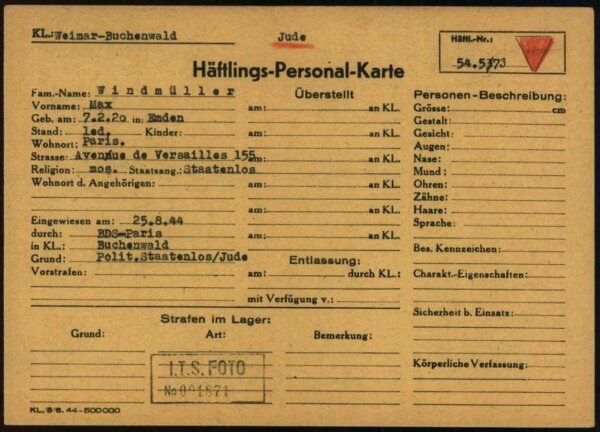

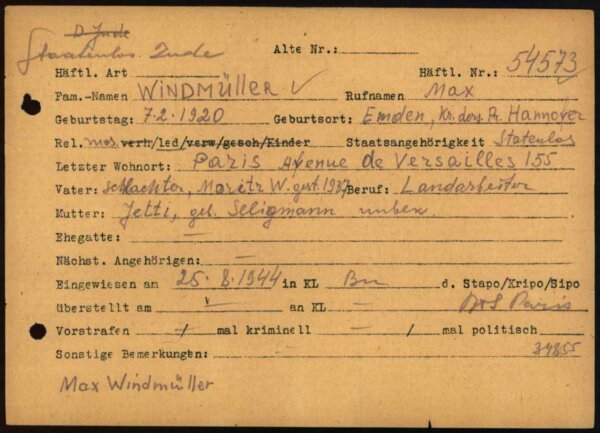

One of the things that impressed the young people was the search for information about the fate of Max Windmüller in the online archive of the Arolsen Archives. “It was the local connection that made looking at Windmüller’s documents such a special experience. Seeing ‘Emden’ right there on the prisoner registration card made much more of an impression,” reported German teacher Kai Gembler.

This prisoner registration card for Max Müller gives Emden as his place of birth.

Remembrance with #everynamecounts

The participants used the new digital introduction to #everynamecounts to familiarize themselves with the documents and then practiced together to learn how indexing works. Then everyone went onto the crowdsourcing platform and worked on documents on their own before coming together again at the end to talk about their thoughts and feelings. “These pre-printed forms are another very clear indication of the intention to commit mass murder. When you see it right there in front of you, you understand much more,” commented one student at the end of the video conference.

Later in the afternoon, the “Keep the Memory Alive!” group had the opportunity to talk to Arie Windmüller, Max Windmüller’s nephew, and the students of the Israeli partner school of the Max Windmüller Gymnasium during a digital meeting.

#everynamecounts meets „Keep the Memory Alive!”

In view of the dwindling numbers of survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust, the young people in the project group want to keep the memory alive and carry it on into the future. “Keep the Memory Alive!” provides a platform for talking about history, planning campaigns, and helping to keep remembrance alive. #everynamecounts fits in perfectly with these goals. The project uses original documents to establish a direct connection with history. By recording the data they contain, the volunteers play an active role in fighting forgetting. And the fact that access to #everynamecounts is digital makes it ideal for the current period of distance learning.

“They’re not just facsimiles, they’re real prisoner registration cards, real documents that students can engage with in a meaningful way and with a lasting impact.”

Kai Gembler, German teacher at the Max-Windmüller-Gymnasium and head of the project group

The resistance fighter Max Windmüller

Max Windmüller, born on February 7, 1920, in Emden, was a German resistance fighter. In 1933, when he was 13 years old, he fled with his family to the Netherlands to escape antisemitic persecution. Together with his older brother Isaak, he joined a group that was helping young people emigrate to Palestine. When the German Wehrmacht occupied the Netherlands in 1940, Windmüller, like many other Jews, went underground. During this period, he first became involved with the Westerweel group.

Windmüller was caught and imprisoned following a rescue operation for thirty Jewish children who were to be deported to the Westerbork transit camp. He managed to escape, and he obtained new identity papers. Under the alias “Cornelius Andringa”, or “Cor” for short, he functioned as a middleman in France and helped organize escape routes to southern Europe. He saved about 100 young people from deportation – his younger brother Emil was one of them.

In our online archive you’ll find various documents on Max Windmüller.

In July 1944, the Gestapo stormed a meeting of the Jewish resistance in France, arrested and tortured Windmüller and his fellow fighters, and deported them to the Drancy assembly camp. In the last transport that left Drancy before the liberation, the Nazis deported him to Buchenwald concentration camp. From September 1944 to March 1945, he performed forced labor for Eisen- und Hüttenwerke A.G. in the Bochum sub-camp. Shortly afterwards, the National Socialists transported him to Flossenbürg during the evacuation of Buchenwald concentration camp. An SS man shot Max Windmüller on the death march to Dachau concentration camp. Weakened by fever and pneumonia, he had left the column of prisoners to take a short rest.

Through their efforts, the Westerweel Group and Max Windmüller managed to save the lives of 393 Jewish children and young people. The Max-Windmüller-Gymnasium adopted his name in 2015 to honor his memory. The Arolsen Archives welcome the commitment shown by the pupils of this UNESCO associated school and are very pleased to be able to reach out to young people in particular through #everynamecounts. Pupils at the Max-Windmüller-Gymnasium are planning to index documents together again on April 21, this time as part of the activities to mark the anniversary of Max Windmüller’s death.