Evidence for the Nuremberg War Criminals Trial

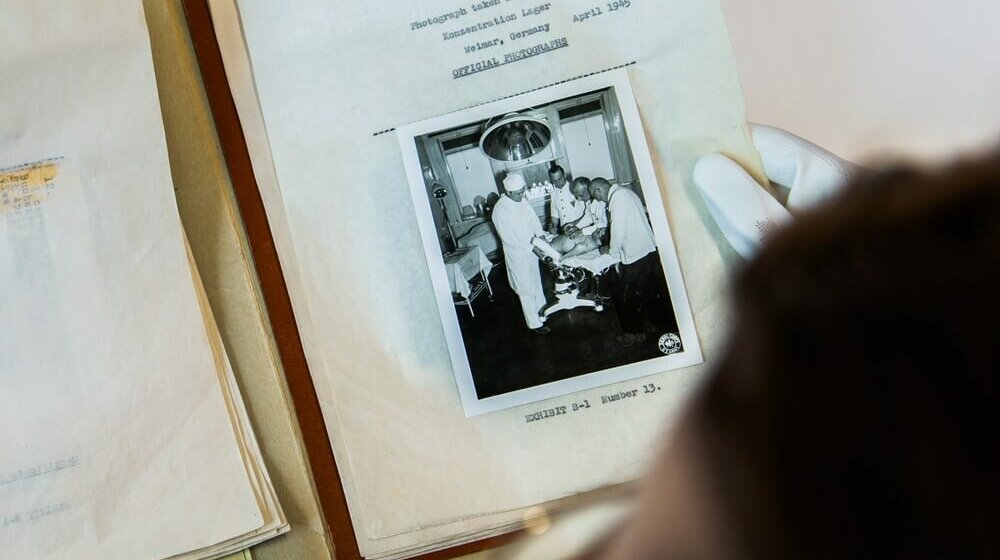

Already within days of the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp, photographers of the U.S. Army Signal Corps began documenting the conditions there. A few months later, twenty-eight of the photographs they had taken between April 21 and 24, 1945 served as evidence (“Exhibit B-1”) in the Nuremberg Major War Criminals Trial. For that purpose, 4x5-inch prints of the photos were mounted individually on paper, numbered and furnished with the heading “Photographs taken at Buchenwald Konzentration Lager Weimar, Germany April 1945.” An American army investigator authenticated each photo on the back.

Only a few copies of the portfolio, which was classified as “confidential,” were reportedly in circulation in the Nuremberg courtroom. The copy in the holdings of the Arolsen Archives is labelled “Set No. 5” and contains various comments, some handwritten. However, we know only very little about the photographers and the exact circumstances under which the photos were taken, to say nothing of how the survivors felt in the situation. Nor can we reconstruct how the portfolio made its way to Bad Arolsen.

Apart from liberated men, adolescents and small children seen inside and outside the barracks of the so-called Little Camp, the photo series documents SS torture methods as re-enacted by Buchenwald survivors before the cameras with the aid of life-size dolls. Together the pictures convey a detailed overview of all the testimonies to SS atrocities the American Allies came upon when they liberated the camp.

The photo seen here tells an entirely different story. In it, we see four men in white coats treating a liberated inmate “in one of the hospital buildings,” as noted on the back. They are in the operating room of the former SS infirmary. The scene doesn’t show a crime, but it does document how well equipped the operating room was. The only person whose name and identity we know is the Czech Miloslav Matoušek (3rd fr. r.). Until his arrest by the Gestapo in Prague on September 1, 1939, he had worked as an internist and obstetrician and been actively involved in a human rights organization. The thirty-nine-year-old was already in Buchenwald as a political inmate by the end of September. The triangular badge on his doctor’s coat is clearly visible, even if the black-and-white photo doesn’t reveal its red color. In August 1942, the camp physician assigned Matoušek to service as a medical orderly in the inmates’ infirmary. After the liberation, he wrote an essay on his experiences and the actions of the SS doctors, which were entirely inconsistent with medical ethics. Buchenwald Through a Doctor’s Eyes was published in Prague in June 1946, only a few months before the pronouncement of judgement in the Nuremberg Major War Criminals Trial.

Even if the photos in Nuremberg Trial “Exhibit B-1” served as evidence of the crimes committed in the concentration camp, the shot of the operating room doesn’t permit us to draw any conclusions about the medical conditions in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Like the other twenty-seven photos, it shows a very specific detail of the time after the camp’s liberation. Its relevance for the courtroom is the evidence it provides of the operating room’s modern equipment. The SS doctors didn’t care about the health of their inmate patients, however. On the contrary, they contributed to the inmates’ selection and murder and carried out medical experiments on them.

These photographs and those taken in other liberated concentration camps went around the world. Historians have recently set about trying to reconstruct the circumstances of their taking and identify the survivors pictured in them by name.

(Kim Dresel, Arolsen Archives, Referat Archivische Erschließung)