Faces of Survivors

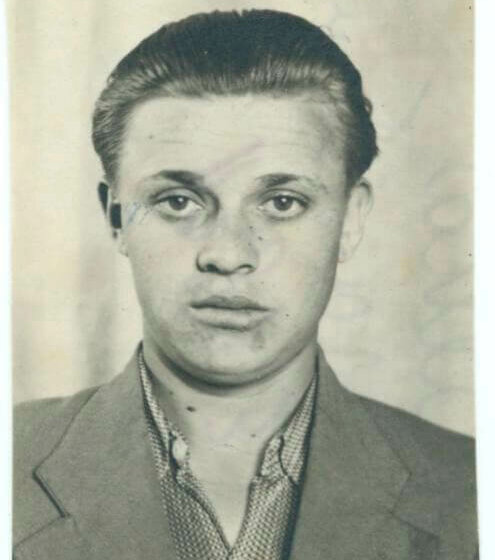

The ITS has uncovered a card index of rare value: a photo card file from the former Dachau concentration camp dating from the first year after the war. The file contains approximately 2,000 photos of survivors—and thus gives faces to the fates of former prisoners such as the young forced laborer and concentration camp inmate Stanislaw Galka or Elias Karl Fridman, who was arrested several times.

It is a small but special card file that went unnoticed for many decades because it was hardly relevant for the ITS’s work of tracing individuals. Containing some 2,000 photos of Dachau concentration camp survivors, it was created for victims of Nazi persecution who needed certificates of their imprisonment to receive support from relief organizations. To prove that they had been in the Dachau camp, and how long they had spent time there, they had to submit two photos of themselves—one for the files, and one to glue to the certificate. This was intended as a way of preventing forgery. The card index later passed into the holdings of the ITS. The documents have meanwhile been digitized and indexed, making it possible to search them by name or birthdate. They will go online in the spring of 2019.

“Photos are especially valuable because we have only very few of them, and even fewer in the original,” says ITS staff member Franziska Schubert, who oversaw the project. “What we have here, for the most part, are not documents made by the perpetrators, but photos the survivors submitted themselves.” Many of them are pictured in casual clothing, some in uniform, and a small number in inmates’ suits—presumably because shortly after their liberation they had nothing else to wear.

“Sometimes the old look at the young faces offers a clue as to what the people went through,” Schubert points out. For example Stanislaw Galka, a young man in a shirt and sports jacket who seems to be looking straight through the camera. The Nazis forced the Polish farmworker to work in an engine factory in Friedrichshafen at the age of sixteen, and in early 1945 deported him to the Dachau concentration camp. He survived and placed an application for official recognition of his custody soon after his liberation. It was presumably in the displaced persons camp that he met his later wife Stefania, with whom he emigrated to the U.S. in 1951.

In the case of the Hungarian concentration camp inmate Elias Karl Fridman, the certificate, complete with the photo of him, has come down to us. He is wearing a uniform cap and a shirt and tie; his shoulders are drooping and his gaze is averted. The Nazis arrested the electrical engineer for being a “jüdischer Mischling”—that is, a person of both “Aryan” and Jewish ancestry—in 1939 and assigned him to forced labor at the Prague airport, from where he escaped. For a year he managed to work at the Vienna Volksoper without being recognized. Then the Nazis arrested him again, and an odyssey began that took him to various concentration camps and prisons in Prague, Terezín, Dresden, Auschwitz, Warsaw and Dachau as well as the Mühldorf subcamp. After his liberation he went to Prague and later to the U.S., as we know from an inquiry of 1981.