Forgotten victims: Italian military internees

Roberto Zamboni is an Italian who has spent almost three decades tracing the so-called Italian military internees who died in German captivity. His project is called “Dimenticati di Stato” (English: The Forgotten of the State). The soldiers were buried in Germany, Austria, and Poland without their families’ knowledge.

When Italy signed an armistice with the Allies in September 1943, the Wehrmacht took some 600,000 Italian soldiers prisoner. The men were deported to Germany as so-called “military internees” and had to perform forced labor. About 50,000 were either murdered or died as a result of the conditions under which they were held.

The only way to escape forced labor was to join the Wehrmacht. But three-quarters of the imprisoned Italian soldiers refused. Because of their special status and the long delay in recognizing them as victims of Nazi persecution, their fate often remained unclear, and their families knew nothing about their whereabouts.

The SS deported Luciano Zamboni to a concentration camp in 1945

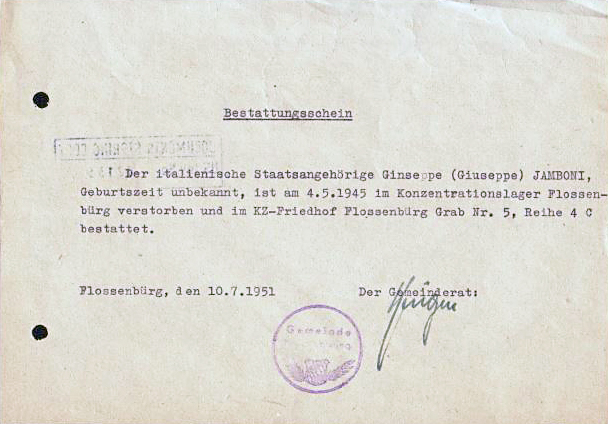

That was the situation the Zamboni family found themselves in. Luciano Giovanni Zamboni was arrested by the Black Fascist Brigades in Verona on December 16, 1944. On January 12, 1945, the SS deported him to the German concentration camp Flossenbürg. He lived to see the liberation of the camp by US troops, but died there shortly afterwards on May 4, 1945.

In this interview, his nephew Roberto Zamboni tells us all about the search for his uncle and talks about how his uncle’s fate made him want to help other Italian families find their relatives. This is also a way of commemorating the victims. The online archive of the Arolsen Archives is one of the resources that help him with this work.

»No one really wanted to talk about it, because the memories tore open a wound that had never fully healed. In the end it was my mother who told me what had happened to Uncle Luciano.«

Roberto Zamboni, nephew of Luciano Giovanni Zamboni

What made you decide to search for your uncle in the first place – did you already know anything about his past?

I was just a child when I first heard that I had an uncle who was deported by the Germans and murdered in a concentration camp. I heard about it from my grandmother and from one of my aunts; sometimes my father mentioned it too. But no one really wanted to talk about it, because the memories tore open a wound that had never fully healed. In the end it was my mother who told me what had happened to Uncle Luciano. After completing his compulsory military service, he was granted a temporary indefinite leave of absence in 1942 and was called up on September 8, 1943. After that, the whole story became very confusing. The only thing we knew for certain was that he had ended up in a German concentration camp and had never returned.

I decided to investigate what had happened and reconstruct the last months of his life in the hope that we would be able to bring his remains home. My mother received the box containing his remains shortly before her death.

Many relatives did not know about the cemeteries of honor

So how did you get started on your major tracing project?

I started the project “Dimenticati di Stato” (English: The Forgotten of the State) at the end of the 1990s with the aim of clarifying the fates of more than 16,000 people who died between 1940 and 1946 either in captivity in Germany, Austria, and Poland or as a result of the war. Like my own family, most of the relatives did not know that the Italian General Commissariat for Honoring Fallen Soldiers had organized the burial of their loved ones in cemeteries of honor. They were thought to be “missing.” In addition to the soldiers’ remains, the General Commissariat also recovered the remains of civilian deportees who had died around the time when the camps were being liberated or during the death marches, and they buried them in the cemeteries too. Sixteen thousand and seventy-nine Italians were laid to rest in six war cemeteries. They included 151 women, 46 infants and children under 13 years of age, and 95 adolescents between 14 and 18 years of age.

I began to catalog and digitize the list of all the Italian dead and to put the information online in March 2009. The lists I have compiled (containing over 16,000 names, over 13,000 of which have been verified and cross-checked) constitute the first record of the Italians who died in captivity or as a result of the war and were buried in Austria, Germany and Poland to be published in full since the end of World War II.

For a long time, many families did not know that their relatives had been laid to rest in honorary cemeteries – like this one here in Munich.

How did you go about tracing people?

My first port of call was the Italian Ministry of Defense. Later I worked with public lists of names from local and national newspapers, which led me to the soldiers’ places of birth. The next step was to inform the municipal authorities. I explained the purpose of my research, sent them the data of the persons I was looking for, and asked the authorities to tell the next of kin where their family members were buried and to inform them about the option of repatriating the mortal remains. My first website went online a few years later.

What are the biggest problems you face when searching for relatives and bringing remains back to Italy?

In the early 1990s, trying to find out information about deceased persons was very complicated. Everything was done by snail mail back then. Weeks or months could pass before I received a response to an inquiry. So the research was very demanding and expensive. Things got even more complicated if a search involved more than one deceased person. To make things even more difficult, the Italian Ministry of Defense did not want to give me any information about the victims of the war at first on the grounds that an initiative like mine should not be entrusted to a private individual.

Repatriation of the dead was forbidden for many years

A major problem with the repatriation of fallen soldiers was a 1951 law that categorically prohibited it. Article 4(2) of the Law of January 9, 1951, contains the following words: “Bodies given a final burial by the Commissioner General cannot be handed over to the relatives later.” On December 15, 1997, convinced of the need to change this absurd article of the law, I submitted a request to Luciano Violante, the then President of the Chamber of Deputies. My request was granted within ten months, the law was amended and came into force on October 14, 1999. Unfortunately, the repatriation costs still have to be borne by the people themselves. I have already lodged several petitions opposing this state of affairs, but they have so far been unsuccessful.

A law prohibited repatriation

Many of the victims were buried in municipal cemeteries or close to the camps immediately after the war. The relatives did not know that they were transferred to cemeteries of honor a few years later. Italian law also prohibited their repatriation to Italy. Roberto Zamboni succeeded in getting the law changed.

How were the Arolsen Archives able to help you with the work you do?

As Provincial Councilor of the National Association of Italian Political Deportees from Nazi Concentration Camps (ANED) and grandson of a deportee who died in Flossenbürg, I am very familiar with the Arolsen Archives. My grandfather first contacted your archive in 1964 to request information about my uncle. I have also contacted the archive on a number of occasions and have always received all the documents I asked for. I am aware of the comprehensive documentation held by the Arolsen Archives, and I have always seen the Arolsen Archives as a kind of “memory bank of deportation.”

I was really pleased when I heard that the entire archive was going to be digitized and that it would be put online to make it accessible to all. Ever since I set up the “Dimenticati di Stato” website, I have been receiving inquiries almost every day from relatives of the fallen who are looking for information about the detention of their loved ones. I use the Arolsen Archives database on a regular basis to find the information I need.

In addition to the “Dimenticati di Stato” website, I have also set up an Information page with the Verona branch of ANED to provide information about people from Verona who were deported. The Arolsen Archives proved to be an invaluable resource when we it came to publishing documents on this website.

#everynamecounts ist ein “Beispiel für andere Archive”

We are building a digital memorial with our #everynamecounts project – how important is the digital archive to you?

If I had a bit more time, I would certainly join in and help. This project is implemented on a voluntary basis with the help of many young people, and I think it should serve as an example to other archives. As is often the case, volunteering works best because volunteers work with passion, they put their heart into what they do.

I believe that linking materials and documents that would otherwise stay locked away in archives is the best way to encourage people to learn about our shared past and to ensure that history does not repeat itself. It sounds like a cliché, but I am convinced that it is true.

To date, over 450,000 people have visited the “Dimenticati di Stato” website. For many Italians, it is the first place they turn to when they are looking for missing relatives. Roberto Zamboni would like to continue the website in the future to help clarify people’s fates. We want to thank him for his dedication – and for giving us this interview!