Learning about the Nazi era together

Two history teachers at the Bertolt Brecht School in Darmstadt are trying out new ways of helping their students to learn about Nazi crimes. Instead of using traditional teaching methods and lecturing from the front of the classroom, they offer project work that is exploratory in nature and is based on dialog and cooperation. The focus is on original documents, some of which are from the holdings of the Arolsen Archives.

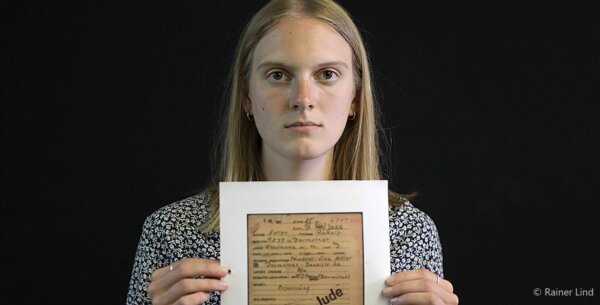

Lessons are often just a “presentation given by the teacher,” criticizes student Hannah Glaser. They are not very enjoyable and this “is actually a sad situation,” comments the 18-year-old school student. She would like to see more dialogue and the opportunity to bring her own ideas and feelings into play. Her thoughts on how students experience the learning situation are part of the final presentation for a project titled “Prozesse der Entrechtung und Verfolgung” which is now available online. It focuses on the deportations of Jewish forced laborers that took place in Darmstadt in 1941. Hannah very much enjoyed working on the project: “What we were doing went beyond what usually takes place within the school system.”

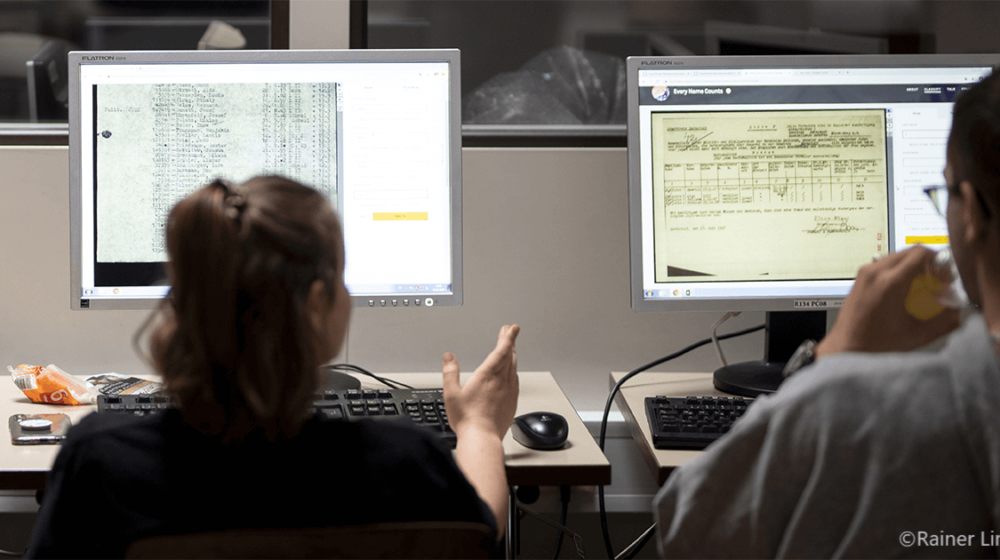

Pupils do their own research

The project team at the Bertolt Brecht School in Darmstadt spent almost a year looking at the life stories of perpetrators and persecutees from the city in the State of Hesse, Germany. “Our approach is to apply research-based learning,” says history teacher Kirsti Ohr, who is responsible for the school project along with her colleague Bernhard Schütz. “We want students to perceive themselves as researchers and search for information independently,” Ohr explains.

Hannah Glaser holds up a document about Rudolf Adler that she indexed with #everynamecounts.

Original documents take center stage

The focus is on original documents which come from various places, such as the Arolsen Archives or state archives in Hesse, for example. The teachers research fates and documents in advance, consult with the archives, and put together a selection of materials for students to use while working on the project. Before the students get started on their own work, they are also given an introduction to the history. “We have a duty to provide context, of course,” explains Bernhard Schütz. Afterwards, however, the students are free to choose how they approach the biographies of perpetrators and persecutees.

“They are often fascinated by surprising details and find their own ways to approach the subject,” reports Kirsti Ohr. The teachers keep a close eye on the research processes and are sometimes amazed by what the young people focus on. “Some of the questions that come up require us to do some research of our own every now and then,” explains Bernhard Schütz. “That’s when the students realize we don’t know everything either,” he says. “But that’s intentional, we actually do research together, it’s a bit like working with colleagues.”

The project promotes “analytical empathy”

The project, which has now been completed, concentrated on the life stories of victims and persecutees from Darmstadt. The project team sifted through perpetrator documents from the concentration camps, and the students were able to find out about the deportation routes and the murder of Darmstadt citizens who were obliged to perform forced labor. Kristi Ohr feels that Nazi injustice is quite a demanding subject for the young people to deal with. “Sometimes information is missing from the documents and ambiguities remain; sometimes the young people come across judgements on claims for reparation filed at a later date that they feel are unjust,” she says. These experiences require and promote “analytical empathy,” the teacher explains.

Since 2017, the results of the students’ research have been incorporated into a commemorative event for the victims of National Socialism, which the city of Darmstadt holds every year on January 27. Because the coronavirus pandemic prevented the event from taking place as usual at the beginning of the year, the project group, which has about 20 members, presented their work on the internet and made a film about the project for the first time. “This fits in with our goal of using the project to have an impact on society as well,” says Bernhard Schütz. The fact that the project workshops which should have taken place at the Max Mannheimer Study Center in Dachau had to be cancelled due to the pandemic was, however, a serious blow. “A lot of persecutees from Darmstadt were imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp, so working with the study center is very important to us,” says Kirsti Ohr.

Student Emma Krämer also participated in the project.

Follow-up project is already underway

The fact that project participants had much less direct contact with one another because of the pandemic was noticeable, but did not have any lasting negative effects. Kirsti Ohr and Bernhard Schütz are already launching the next project. The Bertolt Brecht School is now focusing its attention on the persecution of Sinti and Roma from the State of Hesse. This will involve working with the Association of Sinti and Roma in Hesse for the first time.