“I’m trying to pass the message on” - Interview with Gaëlle Nohant

The work of the Arolsen Archives and the #StolenMemory campaign in particular provided French author Gaëlle Nohant with inspiration for her latest novel, “Le bureau d’éclaircissement des destins.” Published to high acclaim in France, the novel won the “Grand Prix RTL-Lire,” a prestigious literary award. It is scheduled to appear in German in the fall of 2024 under the title “Das Büro zur Klärung von Schicksalen.”

Ms. Nohant, what is your new novel about?

My novel centers on research carried out by Irène, a French archivist who works for the International Tracing Service. At the end of 2016, the protagonist takes on the task of returning three items to the descendants of their former owners, who were deported during the Second World War. Irène’s research sheds light on the fates of many people, not least her own. At the same time, the novel gives readers an insight into the history of the International Tracing Service – from its founding through to the decision to open the archives to the public and to researchers.

How did you hear about the Arolsen Archives and the #StolenMemory campaign?

A friend who had received information from the Arolsen Archives about the fate of her relatives drew my attention to the presence of documents on Robert Desnos in the online archive of the Arolsen Archives. I had written a biographical novel about Desnos and had spent years researching his life, but I had not known about the existence of these documents or the archive. Out of curiosity, I tried to find out as much as I could about the Arolsen Archives. And I came across a number of articles on the campaign to return the prisoners’ personal effects that were found in some concentration camps – #StolenMemory. Straight away, I knew I wanted to write a novel about it.

What intrigued you about the act of returning the personal belongings of people who had been murdered to their families?

First of all, I was fascinated by the symbolic meaning of these objects. Although they are closely associated with a painful history, they are primarily a vivid reminder of the life the deportee led before their ordeal began. All at once, they are restored to their proper position in the family and in life. Nowadays, things are often seen in terms of their market value, and against that background, I find it admirable and important that such lengthy, difficult, and careful research is carried out in order to return an item that is worthless in material terms.

Why do you think it is important for families to get these items back?

I think it is important for them to be able to reconnect with family members who died – or who returned from the concentration camps but hardly ever spoke about that terrible period in their lives. As generations pass, and the deportations – and the black hole they represent – recede into the past, people may find it easier to start looking into their own family history. Returning these objects helps repair a small part of a history that was left in ruins.

It is also a way to honor people who did not return from the war and could not receive a proper burial. The object is a symbol of the body that is missing and can help give someone who disappeared a place among the living again. I can remember one man who, when his great-uncle’s personal effects were returned, discovered that they looked a lot like each other. That, too, is a way for him to connect to his family history.

Have you yourself been present when personal effects have been returned to family members? How would you describe the experience?

I have been present on several occasions when personal effects have been returned to families, and I found the experience very moving. What impressed me most was that although these ceremonies were emotional, they were not sad. To see several generations of a family coming together, children included, actually had something peaceful about it. I think the return of these objects may help families to work through their histories, histories that were often painful and weighed down with unanswered questions and silence.

Return of personal effects in France

The German occupiers sent Hélene Swaczyk to a concentration camp, where she was put to work as a forced laborer. She survived and returned to France after liberation. With the help of volunteers, her personal belongings have now come home at last too.

That is why I find it so important that the #Stolen Memory traveling exhibition will be touring France until the end of 2024, and I hope that more people will learn about the project as a result.

Are there people in your own family who were affected by the Holocaust? Does your book have an autobiographical element?

No one in my family was deported. But the deportations and the Holocaust had a lasting effect on my grandmother. She was a teenager during the war. And she passed this trauma on to her daughters and her grandchildren. I was very young when she told me about war and about the exclusion that preceded the deportations and the deaths in the camps.

Her experience of this history gave her a strong personality and a great sense of solidarity. I always saw her fight injustice and discrimination. I was thinking about her all the time while I was writing. In a sense, the novel is my way of saying to her: “I got the message. Now I’m trying to pass it on.” French resistance fighter Lucie Aubrac, whom I liked very much, once said that the verb “to resist” should always be conjugated in the present tense.

Did you do any research in the Arolsen Archives yourself?

I started working on my novel in the winter of 2020. Lockdowns were still in place then, so the archive was closed. Fortunately though, thanks to digitization, I was able to access a large part of the archive from home, and I spent a lot of time browsing the collections, translating archival material from German or English, and zooming in on documents so that I could study details, abbreviations, and stamps. I also read internal documents from the ITS, the correspondence archivists entered into with people who had submitted inquiries and with other archives. Immersing myself in this chapter of history was a very intensive experience for me.

Did anything make a special impression on you?

One of the things I remember is a report filed by an SS commander to inform his superiors that a certain Russian village was “Judenrein” (“cleansed of Jews”), i.e. the entire Jewish population had been murdered or deported. I was shaken by the sheer coldness of this report. The archive is quite overwhelming, even for people who have already read a lot of first-person accounts or books by historians on the subject. It is a piece of stark reality that hits you straight in the heart.

Another example is a letter that Hugh Elbot, the former interim director of the ITS, wrote to his American superiors in 1952, warning them not to entrust the archive to the Germans. In this letter, he mentions that he had identified 45 SS and Gestapo leaders among the staff. One of them had even tried to set fire to the archive. I found this episode so interesting that I incorporated it into my novel.

Did you base the protagonist, Irène, or any of the other characters in your novel on real people? To what extent is the novel fictional?

I wanted to write a novel because that meant I could take advantage of all the possibilities offered by fiction, but I was keen to make sure the historical facts were accurate at the same time. So I always based my fictional plots and characters on historical reality. I read two hundred books and eyewitness testimonies, watched dozens of documentaries, and combed through countless articles and archives in order to develop the characters and fates that appear in this book.

Sometimes, when I entered the name I had given a fictional character in the online search box, I found a real-life namesake in the archive. The archives contain information about a man called Lazar Engelmann, for example, who was practically the same age as the character in my book and traveled a similar path of persecution. His prisoner registration card from Buchenwald even contained a photo that provided the visual inspiration for my figure.

All the characters in my novel are fictional, but the things the characters experience in the novel were inevitably experienced by real people during the war, and their feelings and their history were shaped and inspired by the feelings and the history of eyewitnesses. Besides placing value on historical accuracy, I also wanted to treat all my characters’ fates with the utmost respect and sensitivity. Behind each character stand all the people who had similar experiences in real life.

The main protagonist, Irène, is also fictional, but her character was shaped by my conversations with Nathalie Letierce-Liebig, the coordinator of the Arolsen Archives Tracing department – in particular by her commitment to the victims and their descendants, her sensitivity, her great empathy, and her reserve. There’s a little bit of me in Irène, too, because I was carrying out the investigations together with her at the same time as I was writing about them. And also because for Irène – and this is true for Nathalie Letierce-Liebig as well as for many other people who work in the service of the victims of National Socialism no doubt – her work is more than just a job. It is a mission, and it does not end when she leaves the office at the end of the day.

Gaëlle Nohant, Nathalie Letierce-Liebig, and George Sougné, a #StolenMemory volunteer, visiting the Arolsen Archives. (Photo: Arolsen Archives)

As for me, this novel occupied my mind pretty much day and night for three years of my life, and I knew this was the price I had to pay if I wanted to do justice to the subject. However, my daughter did not always see it the same way!

Your novel was published in France in January 2023. What was the response like?

The book received a great response, especially from readers and journalists. Many of them had never heard of the Arolsen Archives. Nathalie Letierce-Liebig recognized something of herself in Irène and saw the book as a tribute to her work, and it was her response that touched me most of all.

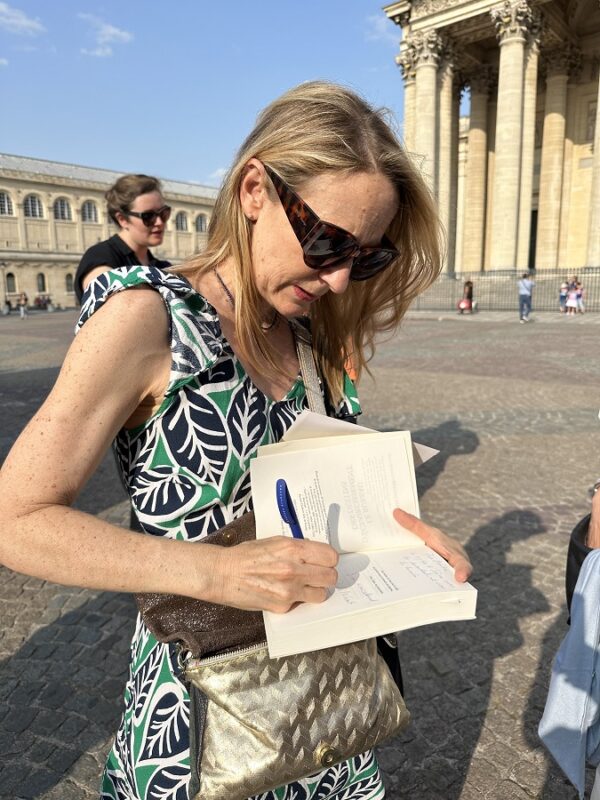

I am also very pleased by the reactions I get from the descendants of victims when they meet me in bookstores and book fairs or when they write to me. I wanted to show my respect for them through my novel. I feel relieved and reassured by the fact that they actually feel that when they read the book. Some of them have told me that they contacted the Arolsen Archives after reading the novel, and in some cases, the Arolsen Archives were able to provide them with information about their relatives.

But I am also moved by conversations I have with young readers. I wrote the novel especially for them. The fact that the book has something to say to them makes me very happy and fills me with hope.

Thank you very much for giving us this interview!

Gaëlle Nohant was born in Paris in 1973. She is a French author and has already published four novels. Her latest novel will be published in England in the summer of 2024; the German translation will be published under the title “Das Büro zur Klärung von Schicksalen” by Piper-Verlag in the fall of 2024. (Photo: Arolsen Archives)