Local Remembrance: Forced labor in Ihringshausen

Next to the old cemetery chapel in Ihringshausen, a village in northern Hesse, Germany, lies a burial ground that has received little attention up until now. Thirty-two forced laborers and children of forced laborers are buried there. Local resident Barbara Wagner has been campaigning for an appropriate place of remembrance to be created for some time now. So far without success.

#everynamecounts: Local Remembrance is an initiative launched by the Arolsen Archives in May 2021 to increase the visibility of local places of remembrance. Because the systematic persecution of millions of people took place everywhere. Ihringshausen – a village with just over 6,400 inhabitants, not far from the city of Kassel – is just one example. The Nazis held about 2,000 people in camps in the village and sent them off from there to perform forced labor. But there are hardly any reminders of these past events in the village today.

Barbara Wagner is from Kassel, but has lived in Ihringshausen for about 30 years. She describes the situation as follows: “Whenever you talk to people who live here about it, they’re always quite amazed. Really? There were forced laborers here?! It’s very important to me that the forced laborers are remembered. That doesn’t mean we need to put up a plaque for all 2,000 of them, but those who are buried here should have their names given back to them at least.”

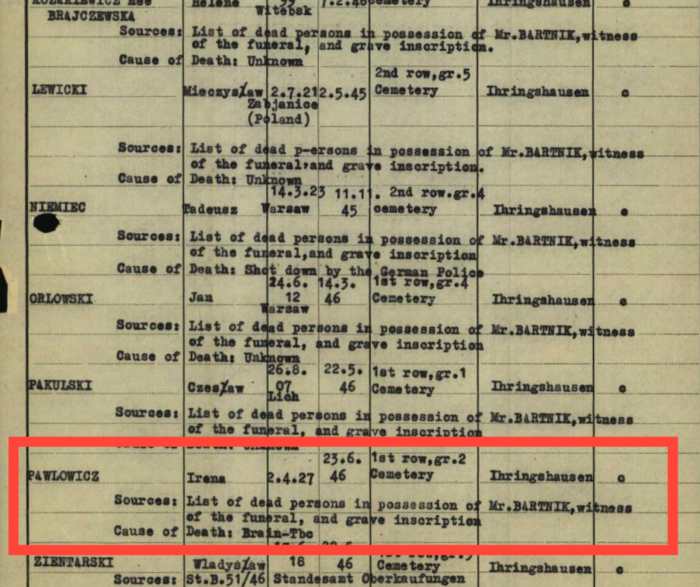

The funerary monument to Irena Pawlowicz

The Polish woman was deployed as a so-called civilian worker at the air base in Eschwege in 1942 – she was just 15 years old at the time. She is thought to have died of tuberculosis of the brain in the Lindenberg Hospital in Kassel-Bettenhausen at the end of June 1946. Some of the documents about her contain different information on her date of death. Her last address is given as the “Hasenheide Polish camp” in Kassel-Bettenhausen.

A total of 32 Polish and Russian forced laborers who died between February 5, 1943, and June 23, 1946, were buried in Ihringshausen: twelve men, four women, and 16 infants. “Forced laborers usually had to work right on up until the last day of their pregnancy, and they had to go straight back to work the day after giving birth; if possible, they would even be sent back to work the same day.” For Barbara Wagner, a former doctor, this treatment is “simply unimaginable.”

Most of the forced laborers did not die until the war had ended. One of the common causes of death was tuberculosis, which spread fast because of their poor living conditions. Only two deaths of adult victims were recorded for 1943/44: According to the certificates, most deaths were due to “accidents.” One example is the death of forced laborer Hanna Goloz, who died in 1943 at the age of 45 in the Ihringshausen munitions plant. The cause of death was recorded as follows: “Fractured skull and internal injuries caused by an industrial accident.”

The graves have precious little to do with “blessed memory”

Only 18 of the victims buried in the cemetery in Ihringshausen have been named so far, but some of the names on the gravestones and tomb slabs are not correct. Many of the inscriptions are barely legible, but the large letters “SP” that adorn all the tombstones have remained intact – the abbreviation of the Polish words “Świętej Pamięci,” which literally translate as “blessed memory.”

For Barbara Wagner, however, the state of the cemetery has precious little to do with “blessed memory.” “The tombstones are disintegrating. They’re made of sandstone, and it’s all crumbling away now. But the only work that gets done here is mowing the grass, that’s it. All our attempts, all our requests to the local authorities to do something to improve the state of the cemetery have so far come to nothing.”

»Without the documents from the Arolsen Archives, I would never have been able to bring all this to light.«

Barbara Wagner, a resident of Ihringshausen

Barbara Wagner was familiar with the graves of the forced laborers through her involvement with a cemetery project run by the local history society. In 2015, she approached the Arolsen Archives and asked them to look for information about the victims. They discovered pages and pages of documents with information about the ordeal the forced laborers went through. In March 2020, a meeting was finally arranged with representatives of the German War Graves Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V.) and the village mayor. Barbara Wagner wanted to discuss what could be done to make the burial ground a more dignified place. “Our mayor suggested paving over the burial ground, installing some benches, and moving the headstones to the back against the hedge. The ladies from the Volksbund and I looked at each other, and our jaws literally dropped; we just took a deep breath.”

A stone slab to preserve their memory

Barbara Wagner then contacted local graphic designer Norbert Städele, who created a design for a fitting memorial. His idea was to engrave the names of the victims on a stone slab, and then lay a little flagstone path around it. In 2021, the proposal was presented to the local authority – again without result. “The wheels of our local bureaucracy have not even begun to turn. I think what we’re seeing here is a total lack of interest,” is the conclusion drawn by Barbara Wagner.

The proposal made by local graphic designer Norbert Städele (photomontage)

Barbara Wagner’s dedication is linked in part to her own background. Her father’s cousin Karl was killed in the war. “Somewhere in the East,” was all the information the family had, and this troubled her father for the rest of his life. “He always had this photo of his cousin Karl; it was very important to him. I think it is always important for relatives that the names of their loved ones aren’t forgotten.”

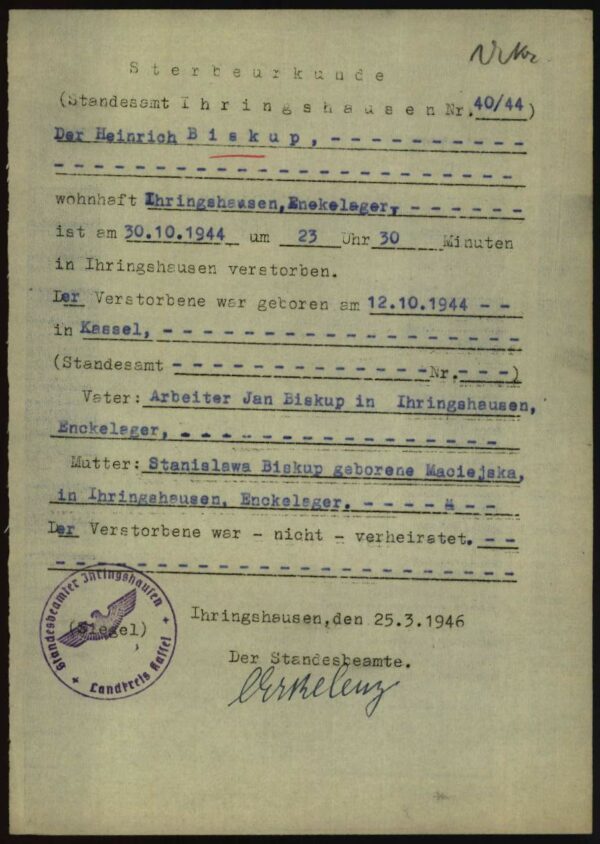

“Too weak to live”

Heinrich or Jerzy Biskup (both first names appear in the documents that have been preserved) died when he was just 18 days old; the cause of death is stated as follows on his death certificate: “Too weak to live, born after eight months in the womb.” His parents, Jan and Stanislawa Biskup, came from Poland and were forced laborers in the Enckellager in Ihringshausen. After the war, the couple was housed at the Kassel-Möncheberg DP camp, where their daughter Leonarda was born in the summer of 1946. The postwar card file contains documents that suggest the family probably returned to Poland shortly after the girl’s birth.

She hopes that progress will be made at the cemetery next year, and that “perhaps in 2022, we will be able to hold an event here on Remembrance Day. Hopefully the slab will be there then with all the names on it.”

Would you like your memorial site to be part of the #everynamecounts: Local Remembrance campaign? If so, please get in touch with us! As part of our cooperation, organizations can profit from the digital infrastructure of the world’s most comprehensive archive on the victims and survivors of National Socialism. Become part of the digital memorial.