Migration with dignity: What the EU can learn from the post-war period

In this interview with historian Dr. Christian Höschler we discuss the subject of “migration with dignity.” He provides fascinating insights into the situation of approximately 10–12 million Displaced Persons in Europe after 1945 and explains how the Allies tried to find them a home.

What parallels do you see between the situation of Displaced Persons back then and the situation of migrants and refugees today?

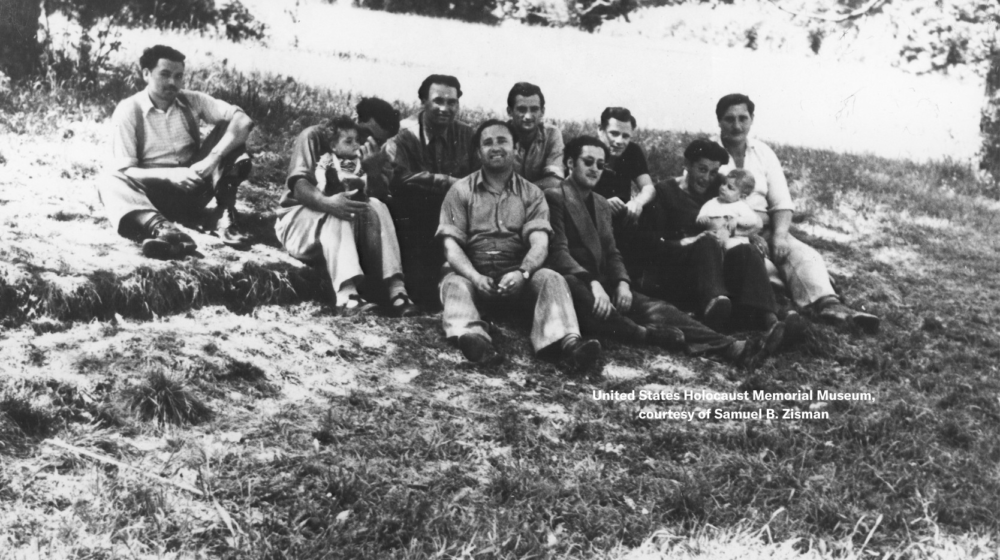

I tend to see parallels at an individual level. The personal experiences of people who are outside of their home country, who are separated from their families, or who are forced to live in camps is largely independent of the political framework or the contexts that led them to flee, for example.

It is the experience of living as a refugee or the experience of displacement that is universal to some extent. Individual fates are unique, of course, but if you compare what it was like to live in a DP camp after 1945 with the situation people encounter in an asylum shelter today and focus on all the related questions about freedom and autonomy in everyday life, you can see clear parallels.

Young child wrapped in a shawl in the Wetzlar DP Camp (Photo: United States Memorial Museum, courtesy of David and Tamara Marcus)

A girl swings in a refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos (Photo: Alea Horst)

Most of the DPs had not come to Germany of their own free will

How would you describe the differences between people in DP camps back then and people in refugee camps now?

The reasons people have for migrating are always different, of course. Some people are voluntary migrants, while others have to leave their home country against their will or are deported. Most of the Displaced Persons had not come to Germany of their own accord. Instead, they had been deported in connection with forced labor, for example, and brought to the German Reich, and they did not want to remain there after 1945. So this was involuntary displacement, and that is something we do not often see in Germany today. Most DPs did not want to stay in Germany back then, but Germany is an attractive destination country for many migrants today.

»One difference between then and now was that there was a common will to face challenges together as an international community of nations. That was a much stronger motivating force in those days than it is now because people had been through these terrible experiences of war, and they knew what national egoism can lead to. If we demonstrated a similarly strong will now, some of the major challenges we are now facing might soon prove less of a challenge.«

Dr. Christian Höschler, Historian at the Arolsen Archives

Can you compare how many people were affected then and how many people we are talking about now?

There were about 10–12 million Displaced Persons in Europe back then and about the same number of expellees. That is a very significant difference when you compare then with now. These two groups alone contained around 20–25 million people who would not normally have been in Germany. And you have to remember that we are talking about a country that had been completely destroyed by the war, its infrastructure was in ruins, supply bottlenecks were an issue, and the work of political and economic reconstruction had to be managed.

Until February 2022, we were talking about a largely intact Europe and dealing with a relatively small number of people who came to us as a result of flight or other migration. If we look at the figures for 2015, that was during the so-called “refugee crisis,” we are “only” talking about a little less than two million people. Since the beginning of the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine, dimensions have changed drastically, though. According to UNHCR, more than 7.8 million Ukrainians* are currently registered as refugees in Europe. Over one million of these are seeking protection in Germany.

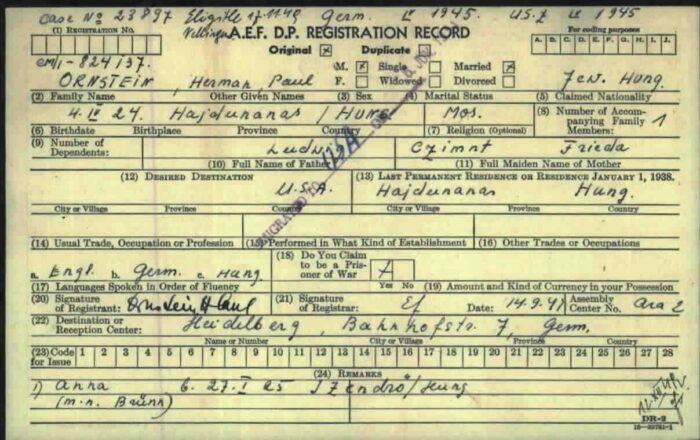

Who were the Displaced Persons?

Displaced Persons were civilians who were not in their home country after 1945 and who could not return to their home country or find a new home without the help of the Allies. Most of them were victims of Nazi persecution who had suffered deportation, forced labor, or concentration camp imprisonment. DP status did not apply to Germans or to ethnic Germans from the former eastern territories of the German Reich.

What strategies did the Allies pursue in their bid to seek out new perspectives for Displaced Persons, and was there such a thing as migration with dignity?

The basic strategy was to repatriate Displaced Persons, i.e. to return them to their home countries, and this proved to be successful in most cases. By the end of 1945, the Allies had managed to repatriate millions of people. However, things did not go entirely to plan, because not all DPs wanted to go home. DPs from the Soviet Union were afraid of reprisals, for example, and in many cases, their fear was justified. To say a few words about dignified migration, this was not always a possibility immediately after the war because forced repatriations took place as well, and that led many Soviet DPs to commit suicide in the camps. The Allies then discontinued the practice of forced repatriation, and the later post-war years saw the emergence of a new principle for dealing with flight and migration that took individuals and their personal wishes and ideas more seriously.

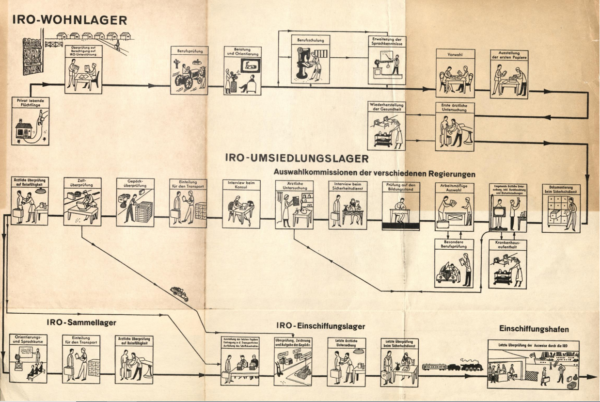

The IRO emigration pipeline shows which stations the DPs had to go through before they could emigrate. In each camp there were different tasks they had to complete, such as meetings with the selection committee, language and vocational classes and customs checks (Photo: Pipeline, in: International Refugee Organization (Hg.): Emigration aus Europa … ein Bericht der Erfahrungen. Genf o.J., o.S.).

In 1947, a new organization called the IRO (International Refugee Organization) replaced UNRRA (the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), the previous organization to be commissioned by the Allies. In addition to repatriating DPs, this new organization was also very explicitly given the task of resettling them. So from mid-1947 on, it was possible to gradually enroll the majority of those DPs who still remained in Germany in resettlement programs. These emigrations to countries such as the USA, Canada, Australia, and South America continued until the end of 1951, when the IRO stopped its work too. This is also seen as the end of the “DP era,” although there were still about 150,000 DPs in Germany at the time. They tended to be old people, invalids, or unskilled workers who were not seen as an asset by receiving countries. This meant that migration with dignity was not an option for them.

Migration with dignity in the sense that people were provided with unconditional humanitarian support was often little more than a facade disguising the brutal economic motives that played a central role. It was not just about helping people in need, the benefit people could bring to the countries that received them was a major consideration as well.

Asylum seekers are forced into inactivity

What can we learn from the post-war period and from the treatment DPs received?

The Allies tried to open up new perspectives for the DPs, and attempts were made to find a solution once it became clear that repatriation was no longer an option for many of them. People were able to learn new professions and new languages in the DP camps to increase their chances of being able to emigrate to the USA, for example. That stands in stark contrast to the situation of asylum seekers, who are housed in shelters where they are more or less forced to be idle and are condemned to a miserable existence until they have been granted asylum status.

Of course, not all the stakeholders were idealists, and national interests had a role to play in the treatment DPs received too, but one difference between then and now was that there was a common will to face challenges together as an international community of nations. That was a much stronger motivating force in those days than it is now because people had been through these terrible experiences of war, and they knew what national egoism can lead to. The situation we are in today is of course very different. On our largely united continent of Europe, which has not seen war for a long time and where prosperity rules, national egoism is on the rise once more. But if we demonstrated a similarly strong will now, some of the major challenges we are now facing might soon prove less of a challenge. The question we have to ask ourselves is this: when can looking back at history teach us useful lessons, and when does it have little to offer? I am convinced that history can provide us with guidance in many areas.