Nazis off the field!

January 27 is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Many of Germany’s soccer stadiums commemorate the persecution and murder of soccer players and club members by carrying out various actions on game days in late January. Back in 2004, the initiative !Nie wieder (Never Again) gave the impulse for this “German Soccer Commemoration Day.” The fan group saw the occasion as a means of actively countering racism, anti-Semitism and violence in the stands.

!Nie wieder has also meanwhile organized its second weekend gathering in Frankfurt under the motto “Remembering is not enough!” From January 11–13, 2019 more than two hundred dedicated members of clubs, associations and fan projects discussed current sociopolitical challenges in soccer and the potentials for learning from (sports) history. The emotional highlight of the event was the encounter with four contemporary witnesses who told their story.

Among the contributors was Christiane Weber, a research associate from the International Tracing Service’s (ITS) research and education department. Along with Anton Löffelmeier from the municipal archive of Munich, she organized the workshop “Giving the Victims a Name – Biographical Research on Jewish Club Members Who Were Expelled, Deported and Murdered.”

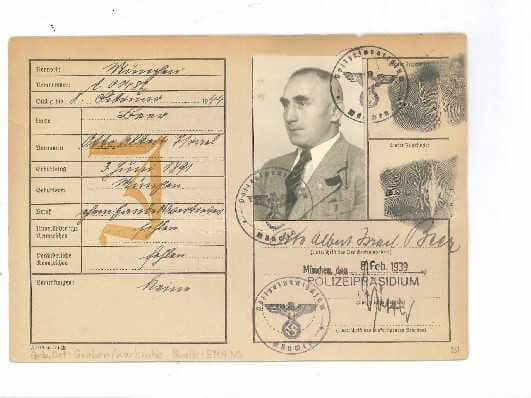

The workshop concentrated primarily on Otto Albert Beer (b. 1891 in Munich), who was in charge of the promotion of young players for the FC Bayern soccer club. On the basis of various documents, the participants were able to retrace how he became a victim of the increasing repressions targeting Jews. In late 1938, the Nazis Aryanized his business. On November 10 of that year, the Night of Broken Glass, he was arrested and imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp for one month. On February 8, 1939, Beer was issued a new identity card. It was imprinted with a “J” and displayed the imposed middle name “Israel,” both of which identified him as a Jew. In 1941, Otto Albert Beer was deported to the Kaunas Ghetto in Lithuania along with his wife and two children and murdered there.

Peter Heering of the FSV Frankfurt fan project described the teamwork that came about during the workshop: “No one sees everything, but together we found out a lot.” By the end, a mere name had become a human being.

Christiane Weber stressed the special significance of soccer in this exploration of history: “We’ve repeatedly experienced that particularly teenagers have a hard time identifying with the victims emotionally. But if someone played soccer in the same club, it creates a bond and paves the way to a deeper understanding.” She was extremely pleased about the many different types of involvement she encountered in the conference participants. “Many of them are active in fan projects devoted to sensitizing fans to Nazi persecution. They organize workshops, for example, or trips to memorials. And there’s a lot of interest in critically examining the clubs’ histories.” Back in 1933, the soccer field wasn’t free of politics either. Many clubs obeyed the directive of the German Soccer Association and expelled Jewish and Communist players and functionaries, but also simple members, sponsors and fans.

Daniel Lörcher, the Borussia Dortmund supporters liaison officer, commented: “Dealing with the past is a never-ending process. It has to be done over and over again.”