Otto Rosenberg: Persecuted as Sinto

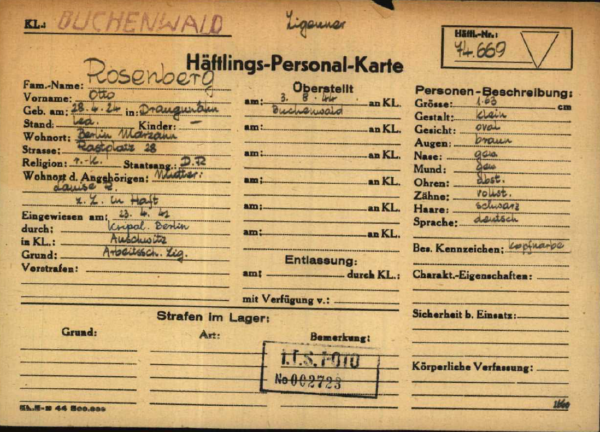

80 years ago and just a few days before his fifteenth birthday, the Nazis deported Otto Rosenberg to the Auschwitz concentration camp. There the SS divested him of all his personal belongings and registered him, tattooing his inmate number Z 6084 on his forearm. Yet his suffering had already begun many years earlier.

Stigmatized as a “gypsy” from an early age, the Sinto born on April 28, 1927 in Draugupönen (East Prussia) grew up with his grandmother in Berlin. Not long before the Olympics in the summer of 1936, the nine-year-old and his family were deported to the Berlin-Marzahn quartering and assembly camp for Roma. Since then, he not only had to live in inhumane conditions and was not permitted to attend school any more, he and his family were also subjected to a “racial biological” assessment by the SS. When he was only thirteen, Otto Rosenberg was assigned to forced labor in an armaments factory in Berlin.

From Auschwitz to Buchenwald to Bergen-Belsen

There someone informed on him in 1942, and he was transferred to the Berlin-Moabit prison for alleged sabotage by the Gestapo. After four months in isolation, he, his parents and his siblings were deported to the so-called “gypsy camp” in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

Early in August 1944, the SS deported the men fit for work to other concentration camps, where they had to perform forced labor. Among them was Otto Rosenberg, who had told the SS he was three years older than he really was in order to survive. He was sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he stayed for a few days only. Otto was forced to do forced labor in the underground tunnels of the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp and of the Ellrich-Juliushütte subcamp. The British Army finally liberated him in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in April 1945. He was the only one of the eleven siblings to survive the Nazi tyranny.

Otto Rosenbergs prisoner registration card. (Photo: Arolsen Archives)

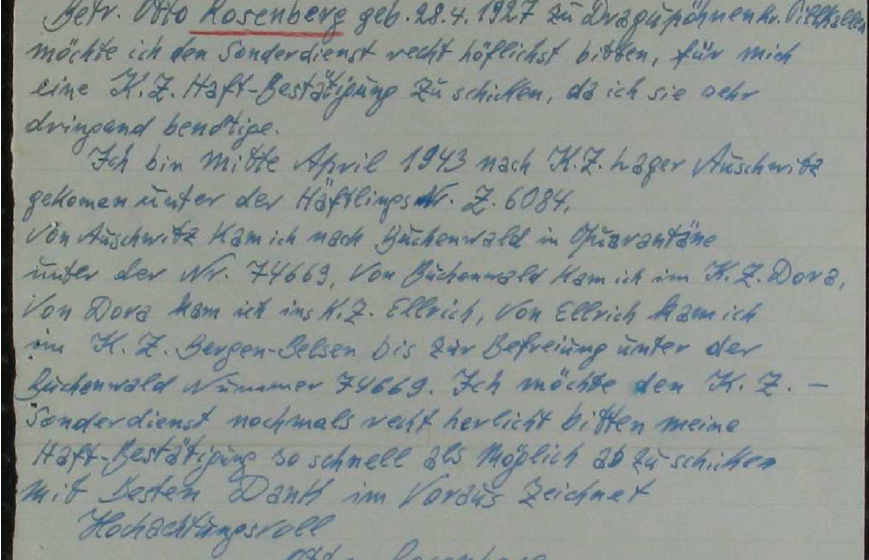

Otto´s fight against antiziganism

In order to receive recognition and compensation for what he had gone through in the various concentration camps, the co-founder and long-time chairman of the Berlin-Brandenburg regional association of German Sinti and Roma contacted the tracing service in Arolsen (today Arolsen Archives) in the 1950s in person – at a time when post-war society continued to stigmatize Sinti and Roma. He requested “most cordially” that a “confirmation of custody” be issued and sent to the responsible compensation authority. Although it was composed many years later, his handwritten letter still testifies to the anguish he had suffered.

In 1998, three years before his death, Otto Rosenberg was awarded the Cross of Merit 1st Class of the Federal Republic of Germany for his special services to understanding between the minority and the majority. He is nevertheless not known to a wide public—unlike his daughter Marianne Rosenberg, who made a career for herself as a pop singer, composer and author.