A sad Easter: Letters from Ukraine

In a collection of letters from the 1940s, our archive employee Hanna Lehun has found some Easter postcards that Ukrainian forced laborers had sent to their families back home. Hanna comes from Ukraine herself. We spoke to her in 2022 and asked Hanna recently for an update in 2023.

What will Easter be like for Ukrainians in 2023?

It has been a very difficult year for all Ukrainians. Everyone is affected by this, everyone knows someone who died in the past twelve months. We usually go to the cemetery during Easter week to remember the dead. But this year, millions of people can’t go home, and many of those who have died in Ukraine either cannot be buried at all or have been buried hastily and without ceremony in mass graves. All over Ukraine, cemeteries are filled with fresh graves decorated with Ukrainian flags – graves of fallen soldiers who fought against the Russian invasion. It is thanks to them that life can go on in the unoccupied parts of Ukraine.

Update: Archives in Ukraine 2023

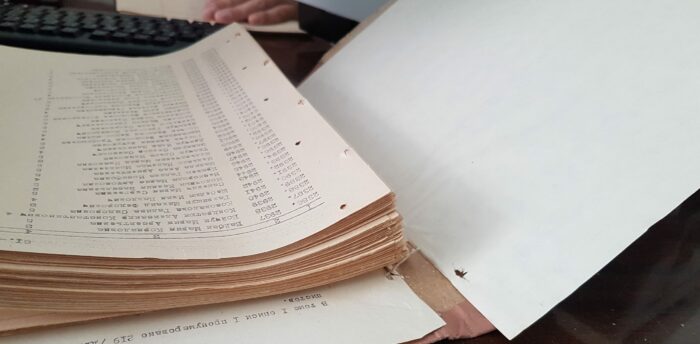

The past year has shown just how quickly important archival material can be lost. Millions of documents from the Kherson region have been stolen and cannot be found. Documents from the archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) have disappeared forever, for example. They contained information on individuals who were oppressed by the state during the Nazi and Soviet eras. The Russian army also looted regional archives. And they mined many of the archives in those areas that have now been liberated, making it impossible for employees to access the documents and save them.

That makes digitizing documents more important than ever. In 2022, the Arolsen Archives signed a contract with the State Archives of the Kirovohrad region on cooperation in the field of digitization. As part of this cooperation, we sent scanners and other equipment to Vinnytsia, Kropyvnytskyi, Ternopil, and to Kyiv.

Which archive holdings do you primarily look after at the Arolsen Archives?

I work with the wartime card index. These are millions of documents that were created about foreign forced laborers in Germany after the war. Many of the people were what were known as “Ostarbeiter” (Eastern workers) and came from the former Soviet Union. In the Archival Description team, we sort and record the archival material and collect further documents about the people who were persecuted by the Nazis. To do this, we also cooperate with other archives, who have interesting holdings.

Hanna Lehun

… lives in Berlin and has been working as a research assistant in the Archival Description department at the Arolsen Archives since 2019. Together with the #everynamecounts team, she also prepares document sub-collections for volunteers to index on the crowdsourcing platform. Hanna studied cultural science, photography, and history in Kyiv, London, and Berlin.

Why do these collections of letters and postcards from the Ukrainian forced laborers exist?

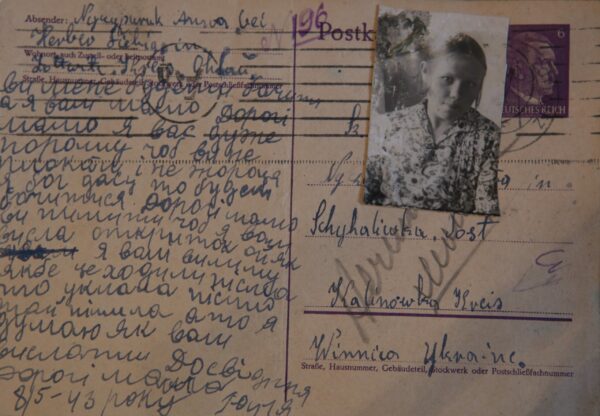

They are part of a long, tragic history of persecution of people from the Soviet Union who were abroad during the Second World War: All those who returned were systematically persecuted in their homeland – even those who had been deported to Germany as forced laborers by the Nazis. The Soviet government suspected them of being traitors and created what were known as filtration files about them, in which they collected all the documents about their time abroad. These letters somehow also ended up in this system – how exactly is unclear. The forced laborers had sent them from Germany to their families in their homeland in order to keep in contact.

Letters from Kyiv and Vinnytsia

Did the letters ever reach the families? Where are they today?

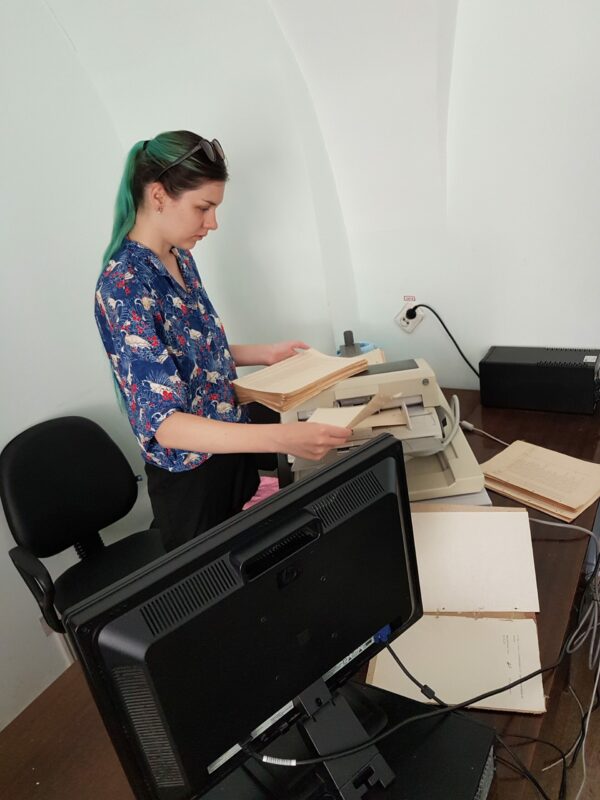

No, most of them were undoubtedly intercepted in the post. These documents can now be found in many archives in the territory of the former Soviet Union. I have mainly worked with the collection from the Vinnytsia State Archive, including on site. I have already produced scans of some of the letters. These digital documents can now be viewed in the online archive of the Arolsen Archives. One of my colleagues has also researched a collection from the State Archive of the Kyiv Region, which is also already available in the online archive.

Working in Ukrainian archives

Within her work for the Archival Description department at the Arolsen Archives, Hanna Lehun also spent several weeks working on site in the Ukrainian archives. During this time, she found interesting new collections, such as the letters from forced laborers, and produced scans for our online archive.

Too few documents are digitized

Have the holdings on the Nazi period and the Second World War in the Ukrainian archives already been digitized?

Unfortunately not all of them. There was no digitization strategy in Ukraine for a long time and so there was no financing and no technology for the archives. This only changed in the last five years with a digitization initiative by the government. Several projects were launched during this time, such as a scan-sharing platform, via which historians share all the scans that they produce during their work in the archives. But it is still far too little. This is now becoming a problem, as some of the archives are at risk due to the Russian war of aggression. My father runs the Vinnytsia State Archive. Although it is still relatively quiet in the region, he has to implement precautions now, under difficult conditions. He wrote to me:

»British colleagues are now helping us to save document scans in a cloud. But we’re having problems with the equipment. One scanner broke immediately before the invasion and now we’re unable to repair it. Two others, which were loaned, had to be returned months ago. This greatly slows down our digitization. Also, some of our female employees have already fled abroad.«

Yuriy Legun, Head of the State Archive of the Vinnytsia Region, Ukraine

Air strikes already hit archives in Ukraine

What have you heard from the historians and other colleagues in the war-torn regions of Ukraine?

Everything is very unclear. My colleague Yuriy Olijnyk runs the State Archive of the Sumy Region, close to the Russian border. Although he wrote to me that some of his collections have already been digitized and the archive building has not yet been damaged, he worries about the many private collections and company and administrative archives that are now at risk.

Are there collections that have already been destroyed?

Yes, unfortunately. The American historian Gregory Aimaro-Parmut has spent years conducting research into the occupation of Ukraine by the Nazis at a large archive of the SBU (Security Service of Ukraine) in Chernihiv. He had plans for the documents and wanted to publish more on the subject. But the SBU building was bombed on the second day of the war. Gregory wrote to me several weeks ago:

»I just found out three days ago that almost everything is lost. I do not have to describe to you as a fellow historian what an unbelievable tragedy this loss is. My colleague Lena and I saved around 1000 files, but this is just a drop in the bucket. Not to mention, since our focus was on the Nazi Occupation, we weren’t able to save so many files related to Stalinist era repressions.«

Gregory Aimaro-Parmut, historian

Historians fled from Ukraine

What’s next for the archives in Ukraine? Do you see any opportunities to work with them again or support them?

There was actually a great deal planned for this year, as the Nazis deported the first forced laborers from Ukraine to Germany exactly 80 years ago. We wanted to work with the archives and historians in Ukraine to expand the e-guide and the crowdsourcing campaign #everynamecounts with stories of the Ukrainian forced laborers. Some workshops and exhibitions had already been prepared. All of that has now been canceled. Many colleagues have already fled. I still haven’t heard anything at all from some of them. I can only hope that they’re doing okay. In any case, we now want to try to help the archives safeguard their documents wherever possible.

In view of the upcoming Easter celebrations, you looked through the forced laborers’ letter collection for Easter messages. What have you found?

Easter is celebrated in Ukraine according to the Orthodox calendar and differs from the dates in Germany. As a result, the Ukrainian forced laborers did not get a day off. However, it’s a very important holiday in Ukraine and a holy day on which people shouldn’t work. Many of the messages are about that. The people write that they are unable to or not allowed to enjoy the holiday, that they are sad, and miss their homeland. Or they reassure their families. Much of that reminds me of the messages that I have now received from friends, colleagues and family: “I’m still alive and reasonably healthy.” For me, that’s no longer just history now, but an everyday reality.

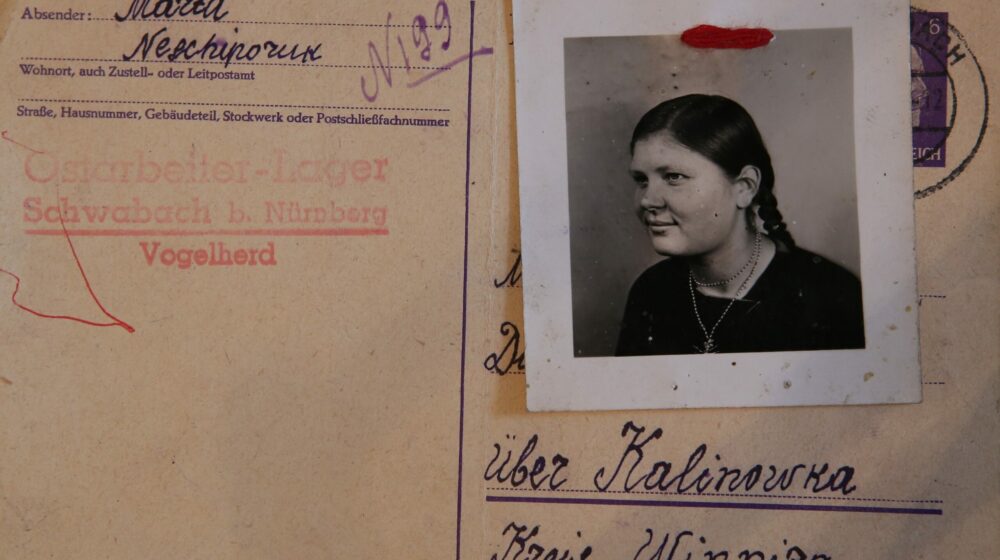

Postcard from forced laborer Hanna Nechyporuk to her mother: “I’m still alive and doing okay … Write to me about how you’ve spent the holiday and whether you at least had some Easter bread … as I was unable to enjoy the holiday. When I think about not being at home, I feel cold from the inside and cry a lot.”

Ukranians face bitter Easter

How is Easter normally celebrated in Ukraine?

It’s a very big, wonderful holiday on which you meet up with all your relatives. Even non-religious people usually celebrate, too, because it’s fun, delicious, and happy. Those who go to church congregate around the building before sunrise. There’s a really festive atmosphere with romantic candlelight, lanterns, and singing. Everyone else meets up with their families later on. People eat a lot, for instance Paska, the traditional Easter bread. Around a week after Easter, people visit the cemeteries, meet with their families there, remember their deceased relatives, and become connected with their own family history. Everything is sure to be different this year. Although people will probably celebrate somehow, it definitely won’t be in the usual cheerful way. I think it’ll be a very bitter Easter.