#StolenMemory: Photos from the time before the Resistance

Siblings, father, and friends: Henri Boula always carried their photos with him. Even when the Nazis deported him to the Neuengamme concentration camp, where he was forced to hand over his personal collection. His niece Arlette Ferahyan has now been given her uncle’s stolen items back by the Arolsen Archives almost 77 years after the end of the war.

Henri Albert Boula was born on March 31, 1922 in the French town of Joinville-le-Pont. His father from Libreville (in what was then the French Congo) had moved to France, where he worked as a private chauffeur. He had a family with a young Belgian woman and brought eight children into the world, including Henri. As Henri Boula and his siblings Robert, Elisabeth, and Geneviève were still very young, when their mother died in 1932, they were looked after by French foster families.

Henri Boula fought in the French Resistance

After the start of the war and the invasion of France by the Germans, Henri Boula was recruited for forced labor. However, he refused to go to Germany and joined the French Resistance in Champigny-sur-Marne in close proximity to Paris. At that time, he had already created his photo collection, which no doubt meant a lot to him personally.

Henri Boula

The pictures show his siblings, friends, and acquaintances. They are snapshots of happy days. Cheerful groups, walks by the river, and picnics outdoors can be seen in the images. Many of the photos bear inscriptions: “To my darling little Henri, to remember your beloved Huguette and to you all my most affectionate and tender kisses,” was written to him by his fiancée on the back of her portrait, for example.

Boula had 30 photos with him when he was arrested

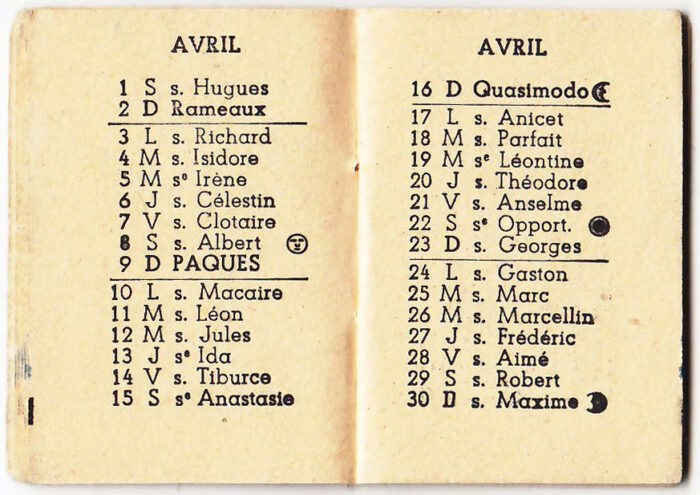

On June 4, 1944, the Nazis arrested Henri Boula and deported him from Compiègne to the Neuengamme concentration camp. There, he was forced to surrender all the items that he carried. Alongside over 30 photos were train tickets, dried flowers, and a small almanac for 1944.

Personal effects

The personal belongings were taken from the prisoners when they were brought to the concentration camp. Henri Boula had over 30 photos with him, some of which were inscribed on the back, and also a train ticket, dried flowers and a small almanac for the year 1944.

Henri Boula did not survive his imprisonment in the concentration camp. It is not possible to say for certain what happened to him. Although his personal belongings were preserved by the International Tracing Service (now the Arolsen Archives) for decades, no further information about his fate can be found in our holdings. A French commemorative book indicates that he is thought to have died at the Sandbostel receiving camp on April 1, 1945. However, an eyewitness wrote to the family to say that Henri died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Over 75 years after Boula’s death, our Belgian volunteer Georges Sougné tracked down the relatives of Henri Boula. Thanks to his help, we have now been able to return Henri Boula’s belongings to his family. His niece Arlette Ferahyan, the daughter of his eldest brother Robert, received the small collection.

Photo from the collection of Henri Boula

#StolenMemory: The search for relatives

Personal effects were taken from the prisoners on arrival at the concentration camp. These include wallets, identification papers, photos, letters, certificates, and occasionally costume jewelry, cigarette cases, wedding rings, watches, and fountain pens. Valuables were confiscated by the Nazis. As a result, the personal effects do not generally have any material value, but are of great sentimental value to the family members of their former owners.

The Arolsen Archives still preserve around 2,500 personal effects of persecuted people from all over Europe in order to return them to their relatives. When searching for the families, the institution relies on the assistance of volunteers like Georges Sougné: People with good knowledge of the country and language skills, who are interested in the history of Nazi persecution and want to undertake the exciting but often laborious on-site research.