“The greatest miracle in the world”

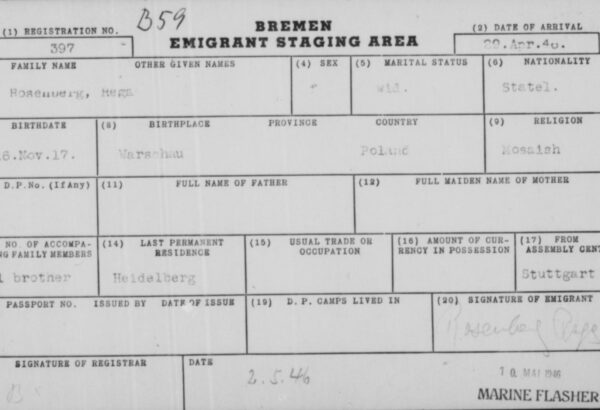

The Mosbach family from Stettin were among the first Holocaust survivors allowed to emigrate to the USA by ship from Bremerhaven in 1946. Their names are registered in the so-called emigration card file. Thirty thousand such documents from the holdings of the Bremen State Archives are being indexed for the latest #everynamecounts challenge.

The S.S. Marine Flasher set sail from Bremerhaven on May 11, 1946. The ship was carrying 867 European “displaced persons, ” deportees who had survived Nazi atrocities in ghettos and camps. One of them was a doctor from Stettin, Dr. Erich Mosbach, who was traveling with his wife Vera, his eleven-year-old daughter Eva, and his parents-in-law Otto and Marta Krüger.

Marine Flasher en route to USA, July 1947. Photo: USHMM / Lola Tanzer

When the ship docked in New York harbor nine days later, the passengers were greeted by cheering crowds on the pier. For the Mosbachs, their greatest wish had come true. After five and a half years of persecution, abuse, and forced labor in camps in Poland and Germany, the family could set foot on American soil at last.

The S.S. Marine Flasher arrives in New York on May 20, 1946. Video: Critical Past LLC

A few months earlier, Erich Mosbach had written the following in a letter to relatives:

“Now we hope […] that the five of us will soon be able to get aboard a ship for emigrants in Bremerhafen [sic] and leave this country where we cannot feel at home any longer, despite all the beautiful speeches and promises, this country which has made us suffer the hardships of life to the bitter end – [we would] rather break stones in America than lead the good life in Germany.”

Dr. Erich Mosbach, circular letter dated 1.1.1946, source: Yad Vashem, item ID 3549211.

How the ordeal began

In February 1940, Erich Mosbach, born on February 26, 1899, in Lüdenscheid, was working as a doctor in Stettin. His wife Vera, thirteen years his junior and a former nurse, was a homemaker; she spent her time looking after their daughter Eva, born in 1934.

On the evening of February 12, the family’s life changed abruptly when the Gestapo ordered the deportation of all the Jews from the Stettin district. The people – who included the residents of two old people’s homes – were driven on foot to the freight station in Stettin in the freezing cold. Their destination was Lublin, around 700 kilometers away. The three-day journey was a torture in itself because the passengers had nothing to drink and suffered terribly from the cold in the unheated carriages.

There were 1007 Jews from Stettin and the surrounding villages on the train. It was one of the earliest systematically organized transports of “evacuees” to camps and ghettos. Only 19 of the deportees would survive the Holocaust, and Erich Mosbach would be the only male survivor.

In Lublin, the deportees were assigned to various ghettos. Some of them lost their shoes in the commotion and had to make the journey in socks in freezing temperatures of minus 35 degrees.

Sent from camp to camp

The Mosbachs were sent to the Bychawa ghetto, where Erich ran the typhus hospital and Vera helped out as a nurse. However, his work usually consisted of little more than recording the patients’ deaths. Nevertheless, the position ensured that the family “had a good life compared with the others,” as Erich put it later, looking back at this period.

In 1942, the Mosbachs had to “resettle” in a ghetto in Belczyce, where they narrowly escaped death when the camp was evacuated. Together with around 100 others, they managed to hide in time, but they could not escape seeing how the rest of the camp’s residents were cruelly murdered.

The survivors managed to bribe officials into setting up a new labor camp in the village. But in May 1943, the Nazis liquidated this camp too. Out of 1,200 residents, only 300 who were deemed “able to work” were sent to other camps – all the others were shot, tortured, executed.

The family passed through more camps, but miraculously they were able to stay together. Not until October 1944 were they separated. Erich was sent to the Groß-Rosen concentration camp near Breslau, where he had to do 12 hours of forced labor a day in the quarry camp. Only with “good luck and cleverness,” as he wrote later, did he escape “the oven.” He was transported to Buchenwald concentration camp as a “special locksmith.”

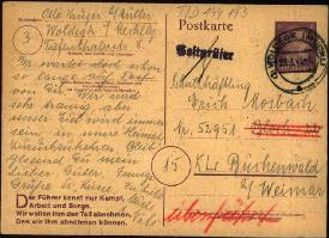

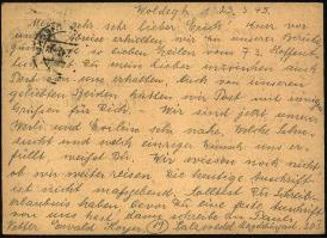

On March 23, 1945, while he was in Buchenwald, Erich Mosbach received a postcard from his stepfather Otto and his mother Marta, sent from Woldegk in Mecklenburg. In it they wrote: “We are very sad, but our goal will always be to return to our home country. Stay healthy, my dear fellow. Warmest greetings & kisses. With love Mum & Dad.” Source: Arolsen Archives, DocID 6661001

Worked to exhaustion

Vera and Eva were transported to Auschwitz first and then sent on to Ravensbrück concentration camp shortly afterwards. As soon as they arrived, Eva and her daughter, who was just ten years old at the time, were forced to work 12 hours a day in a Siemens factory. They endured hunger, cold, and damp. Vera fell ill, but she carried on working despite having a high temperature and went on to develop severe pneumonia, from which she was slow to recover.

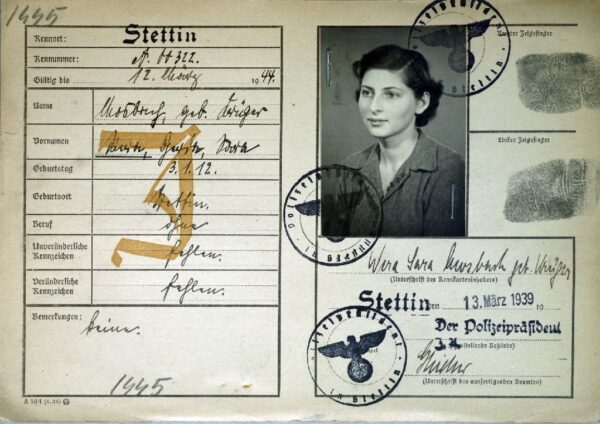

Vera Mosbach’s identification card from the “Stettin Police Headquarters” fonds in the State Archives in Szczecin

„It was like a dream”

Shortly before the Americans liberated Buchenwald concentration camp on April 11, 1945, the Nazis sent the prisoners on forced marches to Füssen in the Allgäu region, a journey that lasted several days. Erich managed to escape into the mountains, where he hid. A few days later, American tanks came rolling through the valley. This is how Erich remembered it: “Racing down − free and human beings again – it was like a dream.”

He entrusted a soldier with a letter to his sister in the United States, and it actually reached her. She contacted the Red Cross Tracing Service to find out where Erich was and to organize a passage on a ship to the USA for him. Meanwhile, Erich was making his way back to Stettin and could not believe his ears when he heard people washing their hands of responsibility.

“And on my way I met the greatest miracle in the world, for nowhere in Germany were there any Nazis, nor had there ever been any! All the people I talked to had of course always been antifascists. …..”

The family is reunited and emigrates

When his wife and daughter finally returned to Stettin on July 1, 1945, the family was reunited. They could hardly believe their luck: “[…] we were all almost mad with joy and could not thank fate enough for having protected us,” wrote Erich.

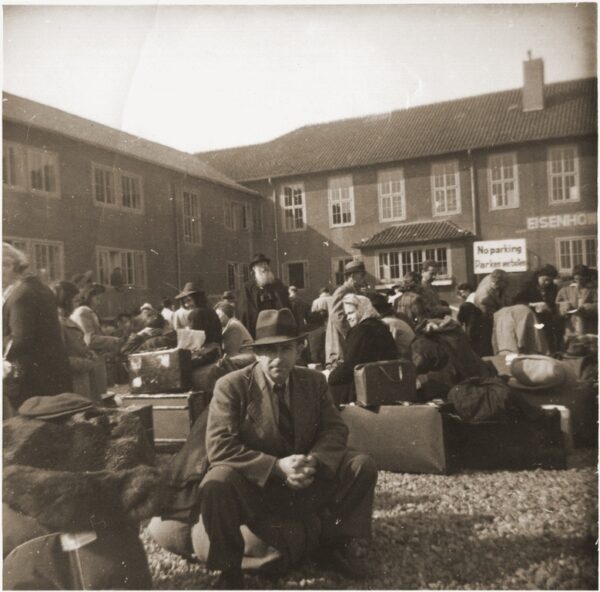

After a brief stopover in Berlin, the family traveled to Bremen and arrived at Camp Grohn on April 29. Shortly afterwards, they were registered to travel to New York on the S.S. Marine Flasher.

Displaced Persons departing Germany for the United States wait with their luggage in Camp Grohn. Photo: USHMM

Index card from the emigration card file for Erich Mosbach and his family. Source: State Archives in Bremen

The ship was the first vessel to transport victims of the Nazi regime from Bremerhaven to the USA. Displaced persons were able to emigrate thanks to the so-called Truman Directive of December 1945. This executive order stipulated that preference be given to victims of Nazi persecution for the issue of visas within the US immigration quota.

After arriving in New York, Erich Mosbach wanted to take his family to Monroe, Louisiana, where his sister and brother-in-law lived. He had plans for his career and wanted to go back to university. Unfortunately, that never happened. On January 20, 1947, Erich Mosbach died in Delaware State Hospital after suffering a stroke.