The return of the stolen books

NSDAP politician Julius Streicher earned a fortune during his time as editor of the antisemitic hate sheet “Der Stürmer.” When the war ended, a large collection of books that had previously been looted from victims of the National Socialist regime was found in the editorial library of the weekly tabloid newspaper. Leibl Rosenberg, a publicist and provenance researcher for Nazi-looted books, has spent over 20 years working to return the books to their rightful owners or their descendants on behalf of the City of Nuremberg.

In this interview, the 72-year-old talks about his work and explains why he uses the online archive of the Arolsen Archives.

About 9,000 books were found in the libraries of Nazi Julius Streicher. How did you manage to find out who they originally belonged to?

About 3,700 of the books contain notes or writing of some kind. I was able to match them to about 2,200 people or institutions. These marks of provenance often provide revealing and moving insights into the circumstances and the fates of people and institutions who were robbed, forced to emigrate, or exterminated during the period of persecution.

How do you find the rightful owners?

One approach we use is to publish search lists on the internet at regular intervals with detailed information about the previous owners. But we also contact potential partners directly if we think they will be able to provide us with information and leads on any of the people we are looking for. These methods put us in touch with people whose families and legal successors were scattered all over the world by Nazi persecution. At the same time, relatives or whistleblowers also often contact us of their own accord. We have managed to return about 800 books so far.

Who did the works originally belong to?

The owners are very diverse. They include Jews, Freemasons, members and functionaries of the workers’ movement, and members of Christian congregations, but also clergymen and scholars, wholesalers and schoolchildren, academies and workers’ sports associations, libraries and bookshops, tradesmen and philosophers. All of them became victims of National Socialist persecution between 1933 and 1945. They were robbed and cheated of their memories, their feelings, and the worlds they knew.

So the looting was intended to hurt people?

Yes, quite definitely. And the value of the stolen works wasn’t necessarily the point. The books are not author’s copies or library copies, the volumes in this collection rather tend to belong to the realm of normal everyday life. It was by no means only scholars, rabbis, priests, bibliophiles, collectors, and dealers who were robbed, perfectly ordinary citizens were targeted too, neighbors, friends, and relatives – people you knew, people you had dealings with, people who went about their daily lives alongside you and whose names are now forgotten.

You use the publicly accessible online archive of the Arolsen Archives to help you search for information. How does it help you?

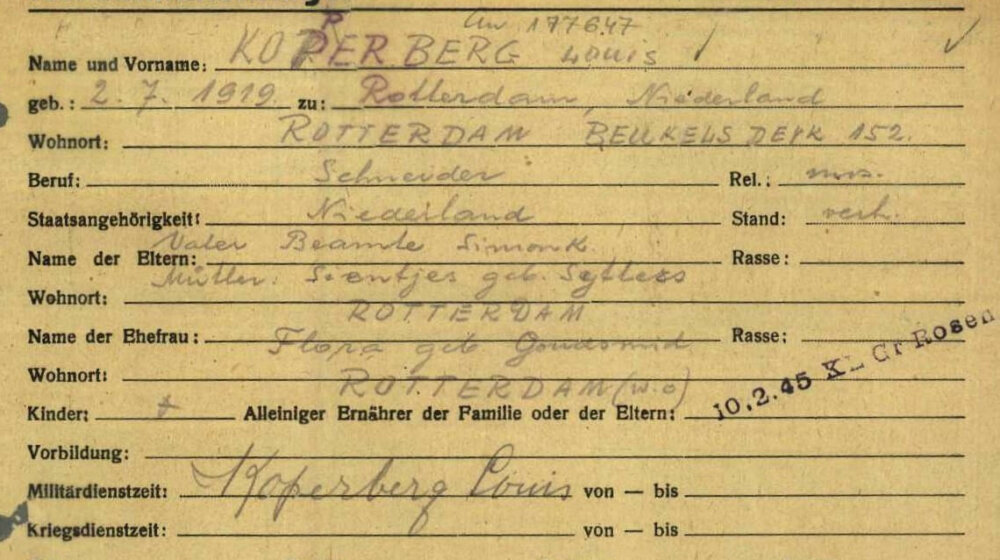

It provides me with more information about names or addresses found in the stolen books. This information makes our search list more effective as it increases the chance that a person’s descendants can actually match a book to one of their ancestors. Because the information we find in the books themselves is often only very fragmentary. But quite apart from that, I feel that the activities of the Arolsen Archives make a very valuable contribution to remembrance work.

Your own work has led you to create a small archive that is also accessible to the public.

That’s right. All the inscriptions and clues to the books’ provenance that we have found in the works in the collection have been recorded faithfully and can be accessed by researchers from all over the world via the electronic catalogue of the Nuremberg City Library. Another step that we have taken in connection with the publication of the documented marks of provenance is to make visual records of these marks available in the form of scans and link these to the appropriate catalogue records in the online catalogue of the Nuremberg City Library. By doing this, we enable people to examine the marks of ownership and compare them with their own records. This can be the first step on the path to eventual restitution.

The number of survivors of the Shoah is decreasing year by year. Does this make the work you are doing to restitute these books even more important?

Yes, I feel certain that the interest shown by first, second, and third generation descendants in the traces that their families left behind will continue to grow. I imagine the Arolsen Archives have similar experiences when they return personal effects to their rightful owners too. Especially when there is no one left alive able to give a firsthand account, books that belonged to those who were murdered or died take on greater significance. Sometimes this can lead to very emotional scenes, which also touch me deeply at a personal level.

Leibl Rosenberg’s parents were Polish Jews; he was born in the Lagerlechfeld DP camp near Landsberg. Since 1997, the publicist has dedicated himself to researching, cataloguing, and returning the looted books that were found amongst the possessions of Gauleiter Julius Streicher after the end of the war. The collection was handed over to the Jewish Community of Nuremberg. It is now on permanent loan to the Nuremberg City Library.