“There was an obvious gap between the Olympic idea and National Socialist ideology”

Authoritarian states make use of their position as hosts of the Olympic Games to demonstrate their strength and exploit the event for propaganda purposes, as history shows. We spoke to Alois Schwarzmüller about the 1936 Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Mr. Schwarzmüller, it is often said that the Olympics lost their innocence at the 1936 Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Do you agree?

My spontaneous answer is yes! Up until then, the Games had always been held in countries that upheld the fundamental values of Olympism: peace between peoples – regard for the value of the individual – respect for sporting achievements. In Greece, France, Switzerland, and the USA, for example, the dignity of the participants had been respected regardless of where they came from, which religion they belonged to, and what their fundamental political convictions were. Hitler and the National Socialists had no intention of adhering to these values.

Stark contrasts: equality versus the privilege of the “master race”

There was an obvious gap between the Olympic idea and National Socialist ideology: The Nazi emphasis on internationality stood in stark contrast to true international understanding; human equality and religious tolerance stood in stark contrast to the Nazi belief in the principle of “might makes right” and the “privileged status of the Nordic race as the master race.” Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, quickly recognized the unique opportunity for the “new National Socialist Germany” to cultivate its image both at home and abroad. He promised the IOC whatever the IOC wanted to hear.

»Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, quickly recognized the unique opportunity for the ›new National Socialist Germany‹ to cultivate its image both at home and abroad. He promised the IOC whatever the IOC wanted to hear.«

Alois Schwarzmüller, local historian from Garmisch-Partenkirchen

What lessons were the National Socialists able to learn for the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin?

The Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen had a special role to play because they served as a trial run for the Berlin Games. The Games were expertly arranged as a “non-political festival of peace.” It was, of course, possible to be deceived, or to allow oneself to be deceived, about the true character of the Games. It was also possible not to (want to) know about Dachau or even to turn a blind eye to the discrimination and persecution of Jewish citizens.

Deceived about the true nature of National Socialism

Today, we know how Jews were tortured and hunted down in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. We know the names and fates of many Dachau prisoners from the district of Garmisch. The Nazis quickly realized that they could use the Olympic Games as a perfect disguise. The great Olympic spectacle in Berlin – with its opening act in Garmisch-Partenkirchen – was an ideal opportunity to deceive foreign countries about the true nature of National Socialism, at least for a while. In the Nazi press, the Games were even seen as an “important instrument for restoring Germany’s standing in the world.” It was in this spirit that Goebbels propagated the slogan “Olympia – a national task.”

Adolf Hitler at the opening ceremony of the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Picture: Bundesarchiv, R 8076 Bild-0008 / Heinrich Hoffmann / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Boycotts have been a recurring theme at the Olympic Games throughout their history. How realistic were the calls to boycott the Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen?

Dictatorship, militarism, antisemitism – the blatant degradation of the Olympic idea gave rise to a wave of indignation, especially in the USA, France, England, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Scandinavian countries, and Czechoslovakia. The aim was to boycott the games in Hitler’s Germany or move them to another country. The decision to award the Winter Games to Garmisch and Partenkirchen was taken at the Vienna session of the IOC in June 1933, and it was during the same session that Hitler’s government had to provide a written guarantee that free access to the German Olympic team would be granted “for all races and religions.”

The boycott against Nazi Germany failed

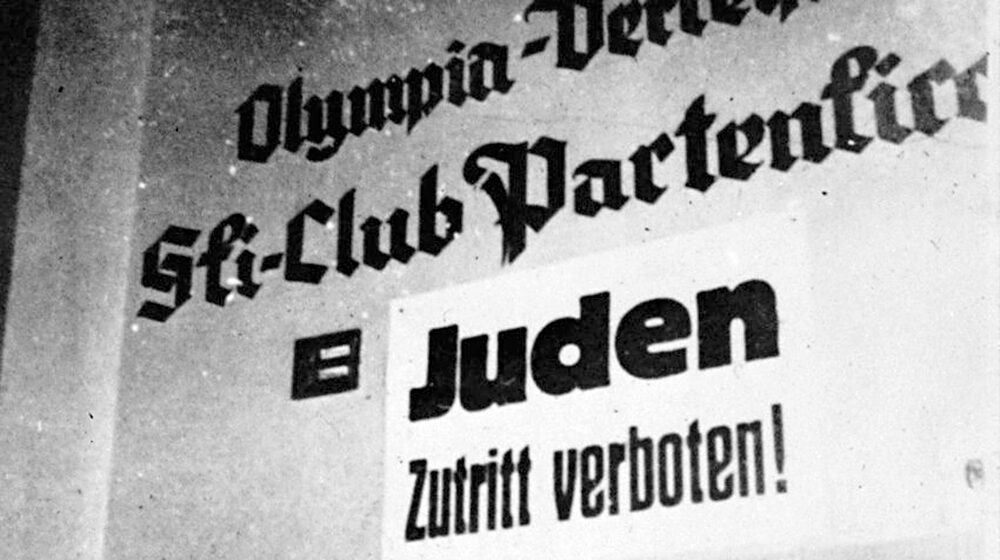

The boycott movement in the United States of America carried the most weight. It was spearheaded by the American Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). It threatened to withdraw American participation in the Games in Germany. Avery Brundage, the president of the American Olympic Committee and an opponent of the boycott, traveled to Nazi Germany in 1934 and “investigated” the situation of Jewish athletes. Brundage made the following cynical comment after talking with German Jews: “In my club in Chicago Jews are not permitted either,” i.e. stop making such a fuss! In the wake of his report, the American boycott movement was ultimately forced to admit defeat. When it came to a vote, the supporters of Olympic participation gained the upper hand with 58 to 56 votes. Pressure from abroad still brought one result shortly before the Olympic Games. Obviously antisemitic posters were taken down in the Olympic town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

The 1936 Winter Olympics

The IV Olympic Winter Games were held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen from February 6–16, 1936. When the Summer Games were awarded to Berlin, Germany also obtained the right to host the Winter Games. With 755 athletes from 28 countries competing in 17 competitions, the Games set a new record. Norway topped the medals table with 7 gold, 5 silver, and 3 bronze medals, ahead of Germany (3-3-0) and Sweden (2-2-3).

So what made the IOC decide to award the Winter Games to Germany again in 1939?

In November 1938, synagogues had been set on fire all over Germany; in March 1939, Hitler’s army had set out to “crush the rest of Czechoslovakia”; and in June 1939, the IOC voted unanimously in London to award the 1940 Winter Games to Germany – admittedly in the absence of Czechoslovakian IOC member Jiří Guth-Jarkovský, as Hitler had refused him permission to travel to London. Sapporo and St. Moritz had previously withdrawn from hosting the Games for various reasons. Hitler did not hesitate for a moment and was quick to take advantage of the opportunity. He was well aware of how the 1936 Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen and Berlin had boosted Germany’s prestige in Europe and the world.

IOC President Baillet-Latour insisted on interpreting the unanimous vote as proof of the IOC’s “freedom from political influence,” ignoring the fact that the IOC had long harbored “pro-fascist tendencies” (Peter Heimerzheim), which was particularly evident in the choice of newly appointed members, most of whom came from authoritarian countries.

Alois Schwarzmüller, a retired teacher, has studied the history of Garmisch-Partenkirchen under National Socialism for many years and is involved in commemorating the Jews who were persecuted and murdered as well as other victims of the regime. In 2011, he got together with three others to create an exhibition titled “The other side of the medal”, which explores the history of the 1936 Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.