“Un-German" boxing

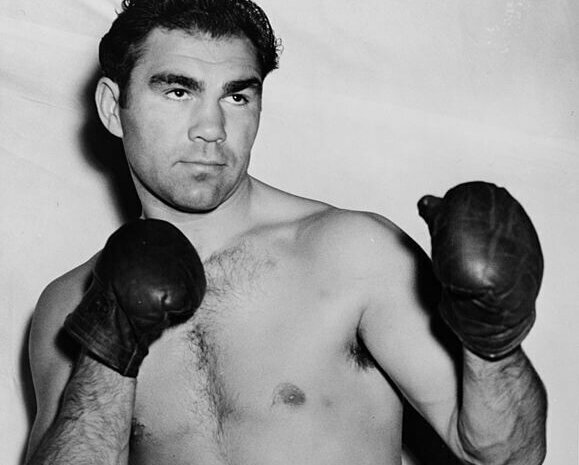

In 1920s Germany, boxing matches evolved into huge sporting events that enjoyed a great deal of media attention. Professional boxer “Rukeli” Trollmann was among the audience’s absolute favorites. He became the German light heavyweight champion in 1933, but the Nazis stripped him of the title a few days later for spurious reasons. They bullied Rukeli because he was a Sinto – but also because of his modern and “un-German” fighting style.

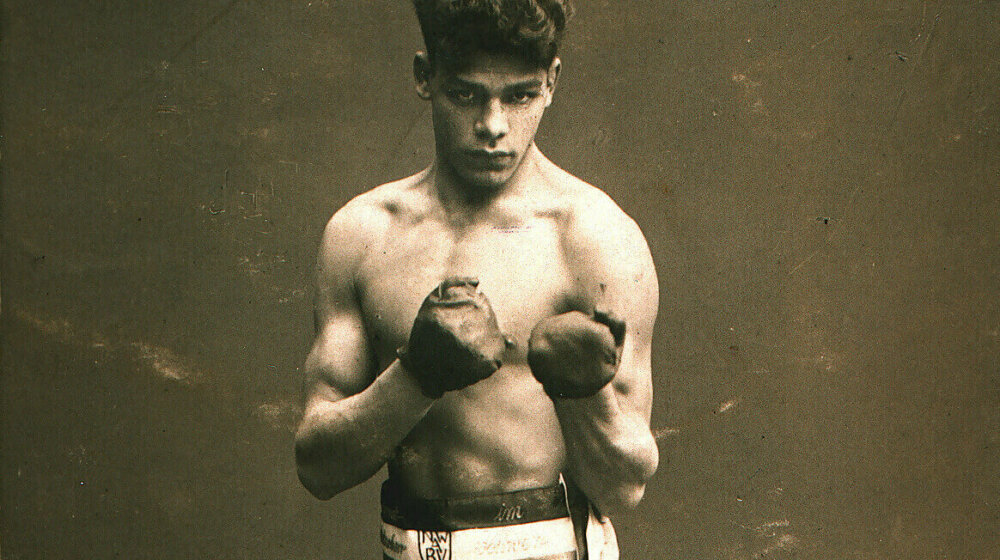

Quick on his feet, athletic, elegant – many saw in Rukeli Trollmann the special boxing style for which Muhammad Ali would later become famous. Rukeli was ahead of his time and beat his opponents with speed and a technique that well-disposed reporters called “fist fencing”. However, some press reviews and sports officials vilified him as a “dancing gypsy” years before the Nazis seized power. Even in 1929, the German Boxing Association removed his name from the list of participants for the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Instead, a weaker boxer was sent who Rukeli had already beat numerous times before.

A meteoric rise

Johann “Rukeli” Trollmann was born into a Sinti family near Gifhorn on December 27, 1907. He gained his nickname Rukeli as a boxer due to his athletic figure: “Ruk” means “tree” in the Romani language. Rukeli grew up in Hanover, where he took up boxing at the age of eight. He was already a four-time regional champion and had won the North German championship by the age of 20. He began a professional career in middleweight and light heavyweight boxing and his fights filled bigger and bigger venues.

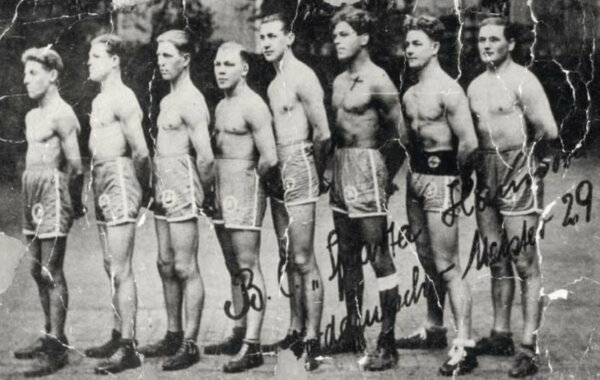

Rukeli (3rd from right) in 1929 with the other amateur boxers from the “Sparta” boxing club in Hanover.

Rukeli only boxed against the best opponents, at national and international level, from 1932 on. He became a problem for the Nazis after they seized power in January 1933, as Rukeli, being a Sinto, undermined the image they wanted to project of superior German fighters. At the same time, he had already become too popular and successful for them to exclude him from boxing without reason.

Stripped of championship title

Rukeli fought for the German championship title in front of 1,500 spectators on June 9, 1933. He was far superior to his opponent. Nevertheless, the judges wanted to score the fight as a tie on the instructions of the Nazi officials who were present. The outraged audience protested until Rukeli was declared the winner. However, the association stripped him of the title just days later. A final boxing match in Berlin ended Rukeli’s career on July 21, 1933. Threats were made to revoke his boxing license if he did not abandon his dance-like style this time and instead “face up to the fight”. Out of protest, Rukeli dyed his hair blonde, powdered his skin white and stood right in front of his opponent. With his arms hanging down at his sides and without any show of resistance, he allowed himself to be knocked out. He lost his boxing license a short time later.

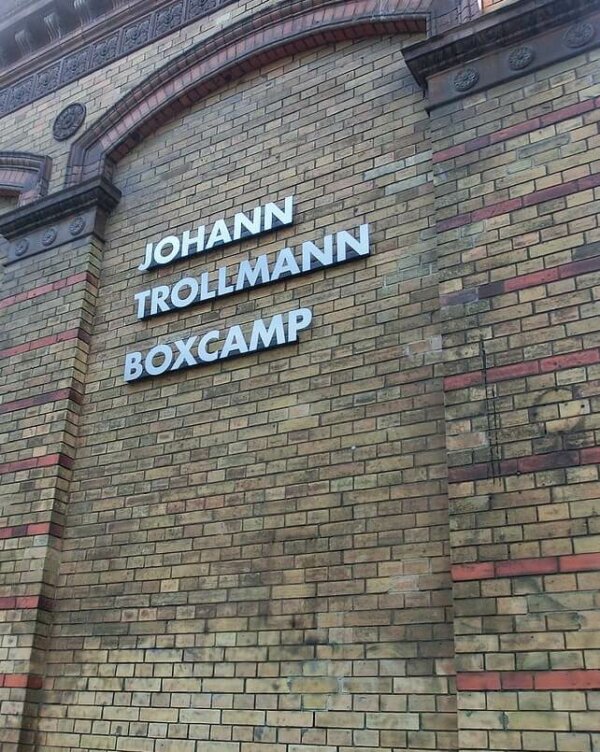

Rukeli Trollmann’s achievements as a sportsman and his tragic persecution were only acknowledged at a late stage. The Association of German Professional Boxers officially recognized him as the 1933 German light heavyweight champion in 2003. The city of Hanover opened a road called “Johann-Trollmann-Weg” one year later. A sports hall in Berlin-Kreuzberg was named after him in 2011 (photo left). There are further memorials in Berlin, Hanover, and Hamburg. Films and plays also remind us of Rukeli’s story today.

»Rukeli’s fate is better-known abroad than in Germany and he enjoys much wider recognition than here. There are numerous exhibitions and even statues for him, especially in the USA and Canada.«

Diana Ramos-Farina, Rukeli’s great-niece and the cultural affairs representative at Rukeli Trollmann e.V.

Persecuted as a “gypsy”

Rukeli married in Berlin in June 1935 and had a daughter in the same year. The enactment of the Nuremberg Race Laws on September 15, 1935, marked the start of a severe ordeal for him, as well as for all Sinti and Roma. Rukeli underwent forced sterilization at the end of December 1935. In 1938, he divorced his wife to protect her and their daughter. He was detained at the Hannover-Ahlem labor camp for several months and was drafted into the German army for military service in 1939. Rukeli fought in Poland, Belgium, France, and on the Eastern Front, where he was wounded. In February 1942, he, like all “gypsies”, was discharged from the Wehrmacht for “racial reasons.” The Gestapo arrested him once again in Hanover in June 1942.

Forced to box

Rukeli was taken to Neuengamme concentration camp, where he not only had to perform the toughest forced labor, but was also constantly ordered to compete in boxing matches in the evenings. He died on February 9, 1943 – according to the original death certificate at the Arolsen Archives, due to “heart and circulatory failure with bronchopneumonia”. Over 20 years later, however, one of his fellow inmates made a witness statement that brought the truth to light. The man claimed to have himself witnessed Rukeli being bullied, tortured, and finally beaten to death with a club at the Wittenberge sub-camp by a kapo (concentration camp inmate with a supervisory role) who had been beaten by Rukeli during a boxing match. This document is also stored at the Arolsen Archives.