Volunteers transcribe 10,000 names

USA, Canada, Israel, Russia, and Poland: volunteers from all over the world took part in our Long Night of the Digital Memorial. To commemorate the victims of the 1938 November pogroms, they recorded the names of around 10,000 prisoners from Dachau concentration camp. Many of the participants took the opportunity to find out about the work of the Arolsen Archives as well – and about what every one of us can do to help.

The participants in our “Virtual Open Archive” came together at a digital event to find out more about what we do at the Arolsen Archives. Christian Höschler gave a talk introducing the organization’s work, and afterwards, about 30 Arolsen Archives employees hosted a range of activities in six virtual breakout rooms: You want to go on a guided tour of our main archives without leaving Ottawa? Or get to know our digital tools from your desk in St. Petersburg? On this special evening, that was no problem: “For me, going on a tour of the actual archive and the exhibition was very informative! All my questions were answered, especially the questions I had about why such an important archive is located in a quiet little town like Arolsen – you would expect it to be in a big city instead,” wrote participant Kirsten Deutsch after the event.

»Seeing these documents was a very emotional experience. They give you a very real sense of just how normal and everyday these events were at the time.«

Adrian, student

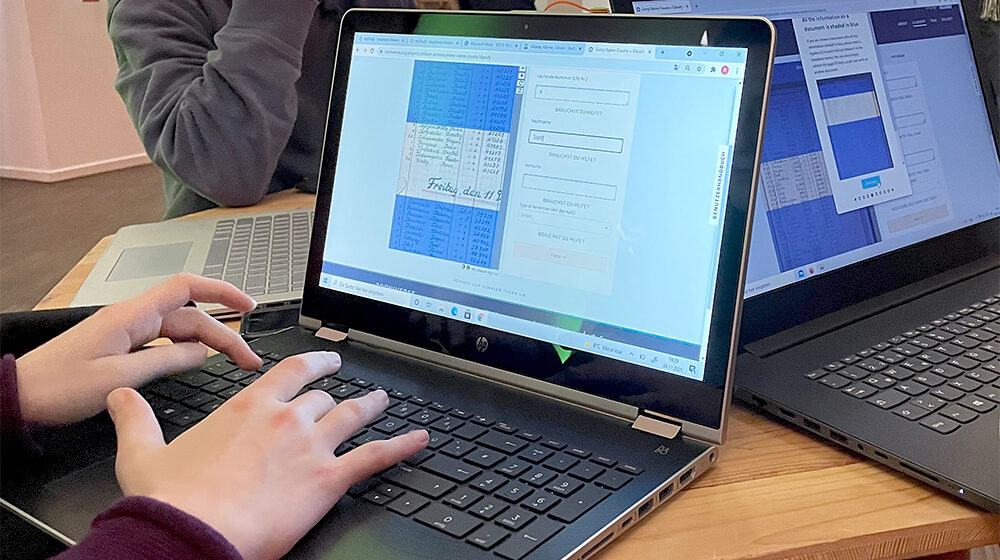

But the real focus of the evening was on our #everynamecounts initiative and on commemorating the victims of the 1938 November pogroms. To mark this anniversary, we provided original documents from Dachau concentration camp and asked participants to record the information they contain in digital form. The collection of the Arolsen Archives includes documents from Dachau that list new admissions to the camp. They show the sudden increase in the number of prisoners held in Dachau concentration camp. The “reason for arrest” recorded for these prisoners was the same in every case: “protective custody Jew.” The original documents show very vividly how on November 9, 1938, and during the days the followed, the isolation and exclusion of a specific segment of the population turned into open violence.

Ten thousand names were digitized on the “Long Night of the Digital Memorial.”

There was also an informative program of events in six virtual rooms.

Active remembrance

By transcribing the prisoners’ names, participants actively commemorated these historical events, most notably the deportation of 30,000 Jews to concentration camps. By the end of the evening, around 10,000 names had been digitized. A high proportion of the participants were students, and their involvement made a real difference. At Pennsylvania State and at the Leuphana University Lüneburg, for example, they met up in groups to work on #everynamecounts together: “Seeing these documents was a very emotional experience. They give you a very real sense of just how normal and everyday these events were at the time. It could have happened to anyone – if you belonged to the wrong group or were born in the wrong place. That really made me think,” remarked a student called Adrian, visibly moved by what he’d seen.

A big thank you goes to everyone who took part, especially to the committee of the Students’ Union in Lüneburg for their hard work and dedication – the Long Night of the Digital Memorial wouldn’t have been possible without you.

There’s still a lot of work to be done on indexing the names of prisoners who were held in Dachau concentration camp! With your help, we want to build a digital memorial to the people who were persecuted by the Nazis. So future generations will be able to remember the victims’ names and identities. But #everynamecounts is about society today, too. Because by looking at the past, we can see where discrimination, racism, and antisemitism can take us.