We look back on one year of #everynamecounts!

The #everynamecounts project was launched one year ago, and a lot has happened since: more than 10 000 volunteers have registered with the project and are helping us to enter the data of Nazi persecutees into our database. Data from more than 2.5 million documents have already been transcribed. And our community exchanged more than 55 000 messages about #everynamecounts.

Deputy Head of Archives, Giora Zwilling, looks back with us on the first year of #everynamecounts. As head of the “Collections and Workflows” team, he supervises the collections of our archive and manages the construction of the workflows, meaning the document packages for indexing. In this interview, he talks about the project’s goals, the surprises encountered along the way, and the plans for the future.

Let’s look back at the beginning of #everynamecounts: how did the idea for the project come about?

The idea developed, because we wanted to make the unique documents stored at the Arolsen Archives accessible to as many people as possible, so we are gradually making more and more of them available in our online archive. However, a document that has been digitized is really just an image. And only when it has been linked to the appropriate keywords will people be able to find it online.

Our aim is to finish linking the names to all the documents in the archive by 2025. It should be possible to find every single name that is on a document in the Arolsen Archives with a simple online search!

And our crowdsourcing initiative #everynamecounts is an important part of achieving this goal.

How does the project work in practice?

We are using “Zooniverse,” a freely accessible platform for citizen science projects that was created by the University of Oxford and the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. Academics from all sorts of different disciplines can use the platform to access support from volunteers when they need people to help them evaluate their data.

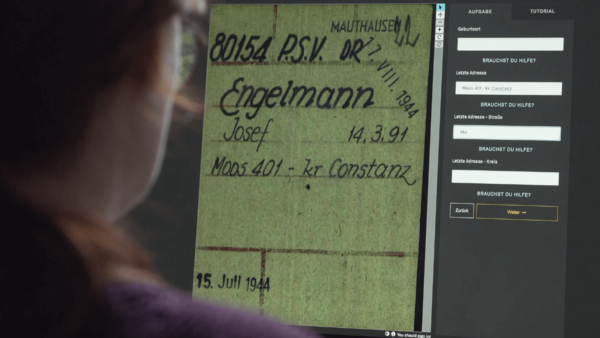

The Arolsen Archives upload selected documents and ask volunteers to transcribe various pieces of information. This process is very intuitive and uses a pre-defined template. Short explanatory texts that are easy to understand help the volunteers to enter the data correctly. We also provide a forum that is moderated by some of my colleagues for discussing any questions which may arise.

This indexing mask is very intuitive and easy to use.

What kind of data are we talking about here?

The names and the dates of birth are the most important pieces of information, of course. But a person’s prisoner category, their last address, and their profession are important too, as this information can be used later to reconstruct the fates both of individuals and of larger groups.

Many documents also list the names of the prisoners’ parents, for example. In the case of Jewish people in particular, we can assume that their parents were persecuted too, although the names of the parents may not be mentioned in any other documents. That makes this information all the more valuable, of course.

And how many names have been transcribed so far?

It isn’t possible to say exactly how many at this stage, because the documents are very diverse. Some workflows contain documents on individual persons. However, since paper became quite scarce towards the end of the war, these cards were sometimes “recycled” and used for a second person too. There is even greater scope for uncertainty when it comes to lists: some include 20 names, while others may contain as many as 150. We will only be able to give an exact figure when we finish evaluating the data and once all the quality checks have been completed.

How do you eliminate errors during data acquisition?

The volunteers work very conscientiously. Many people consult other sources if they are not sure of the spelling of a name or place, for example. But mistakes will always be made. That’s why processing is not defined as complete until the data contained in a document has been entered by three different people. This provides us with three data sets which can then be compared with each other. Deviations are identified during quality control and can be checked and corrected if necessary. Only at this point is the data uploaded to the database that lies at the heart of our online archive.

The project was launched six months ago. What has surprised you most so far?

On January 27, 2020, we ran a pilot project with about 1000 school students from Hesse in Germany. By the end of the day, we could already see how much potential the project had.

Still, none of us were expecting to see the kind of diligence and dedication shown by the volunteers who work on #everynamecounts. Some of our volunteers have been working on the project almost every day since it started. A quick look at the documents they are working on shows what that really means: it probably takes about two hours to type out a list of 100–150 names if the document is difficult to read. And every single one of these lists gets processed three times… The quality of the data is very high! The volunteers use their language skills and their local knowledge to correct errors in the documents. They also share additional information about specific individuals.

Thus, not only our online archive is a digital monument. As part of it, the forum has become a kind of a digital memorial site itself.

Students working with #everynamecounts documents on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, 27.01.2020.

What are the plans for the project’s future?

Since it was launched back in April, the project has been freely accessible on the internet in German and English. Around 9000 registered volunteers are involved.

We want to make #everynamecounts even more visible. We are currently preparing an international campaign that will be launched in a number of countries on January 27, 2021. The project is going to be translated into more languages to make this possible. We are also developing an introduction and an interactive tutorial, which can be used for preparation and follow-up in schools when students work on the project, for example.

We are particularly pleased that #everynamecounts has already enabled us to reach people who had never really thought about Nazi persecution before. By getting involved with the project, they can make a very practical and meaningful contribution to commemorating the victims.

Thank you for taking the time to talk to us, Giora!