You need to keep an open mind:

A conversation with Aya Zarfati

Aya Zarfati, Research Associate at the House of the Wannsee Conference, gave a talk on the clash between archives and family research at our online conference on “Deportations in the Nazi era – Sources and Research.” She described the challenges and the opportunities that many relatives find themselves faced with during their search for information about members of their family. We wanted to know more, so we asked her if we could talk to her about the topic.

Aya Zarfati is a research associate at the House of the Wannsee Conference Memorial and Educational Site. She is particularly interested inVergangenheitsbewältigung (the process of coming to terms with the past) in Israeli and German society as well as in educational approaches to communicating history. She comes from Israel, and has also done some research into her own family history – the history of the persecution and deportation of her relatives in Austria and Croatia. Her experiences are typical of what many third- and fourth-generation descendants encounter when they research their family history. Thanks to the perspectives she brings as an academic, an educator, and a descendant of victims of National Socialism, her insights into the topic are particularly interesting.

The lecture Aya Zarfati gave at the conference was titled “Interaction, Confusion and Potential: On the clash between archives (on Nazi history) and family research.” In this interview, she tells us about some of the experiences she had when she was researching her own family history.

Ms. Zarfati, can you tell us about some of the things you experienced when you were researching the persecution suffered by members of your family?

I became aware of how very dispersed the source materials on the Holocaust are, this applies to biographical research too. The materials tend to be located in many different places where persecution and extermination took place, and this means that they are spread across many different archives too, of course.

I certainly started with a very definite advantage. I had ego-documents written by my great-grandfather, Max Werdisheim. He was persecuted in Austria, where – unlike in other European countries – persecution was well organized, bureaucratized, and faithfully documented. Originally, I also wanted to reconstruct the life stories of some other members of my family, relatives who had fled to Yugoslavia and were then deported and murdered from there, but my research was unsuccessful.

I have had very varied experiences of dealing with databases, online portals, and archives. In my experience, the following factors have a particularly important role to play: their size, the type of financing, the staff, the number of inquiries they have to deal with, and the technological infrastructure that is available.

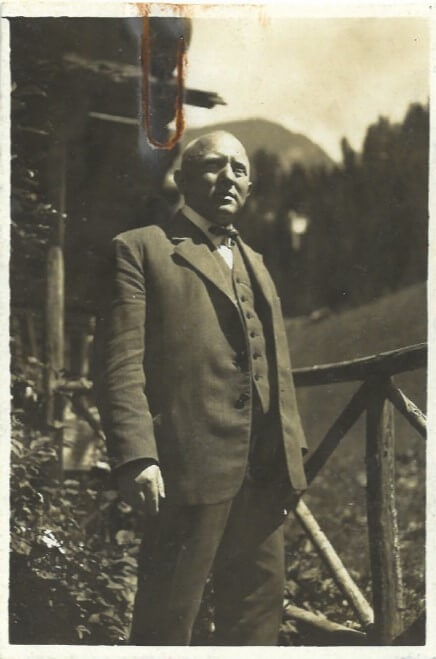

Max Werdisheim, Aya Zarfati’s great-grandfather. She reseached the story of his persecution in various archives and encountred different challenges.

What conclusions can be drawn from all of this when it comes to looking after the interests of relatives who are carrying out research in archives?

Relatives are not historians, and they are not experts. While it is perfectly possible – in theory, at least – for them to find information about members of their family, the situation is difficult in practice because they do not know what to look for, where to look for it, or how to go about it. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that they are often trapped in their own family stories and tend to overlook information that contradicts that narrative. So they need more support and guidance.

You yourself have experienced that not all the stories families tell are told “correctly.” What is your advice to second-, third-, or fourth-generation descendants?

The descendants of victims of persecution need to be aware that the stories that are passed on in families often contain mistakes, or false interpretations of the motives a person had, or misconceptions about the options that were available to them at the time. When relatives stumble upon information that does not correlate with the story they have heard told within the family, it does not necessarily mean that the information in the archive is wrong. You need to keep an open mind and follow every clue.

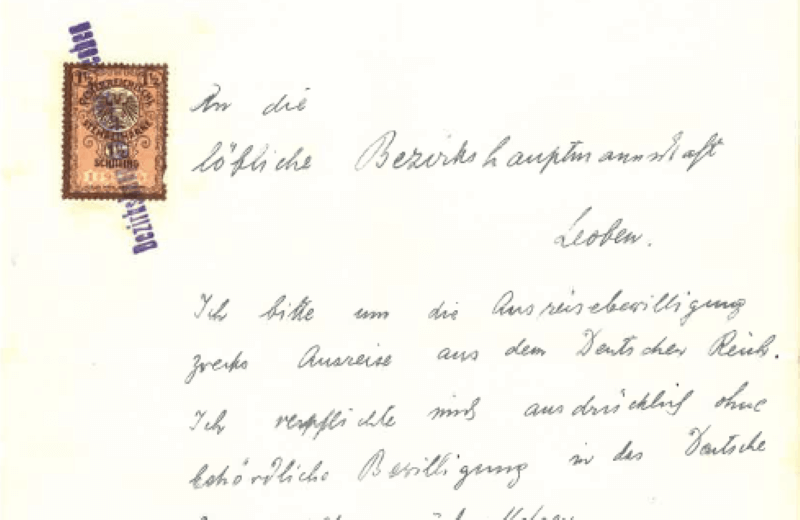

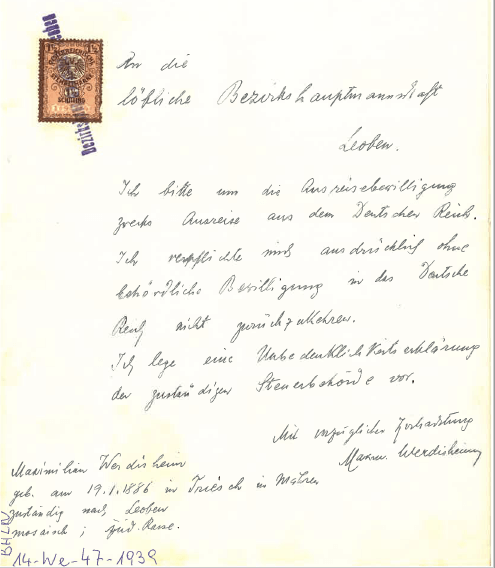

Passport application of Max Werdisheim from April 1938

What has surprised you most during your research so far?

The potential of the source material and the fact that it is also possible to find ego-documents in among perpetrator documents or documents held by the authorities. When I was researching Max Werdisheim, for example, I came across an application for a passport that he had submitted to the Gestapo in Graz in April 1938. What impressed me at a personal level was the way Max Werdisheim “changed” during the course of my research: the sources describe a complex web of events and decision-making processes in which he himself played an active role, exercised at least some degree of agency, and was not a passive victim.

Thank you for taking the time to talk to us, Ms. Zarfati.