Preserving World Heritage

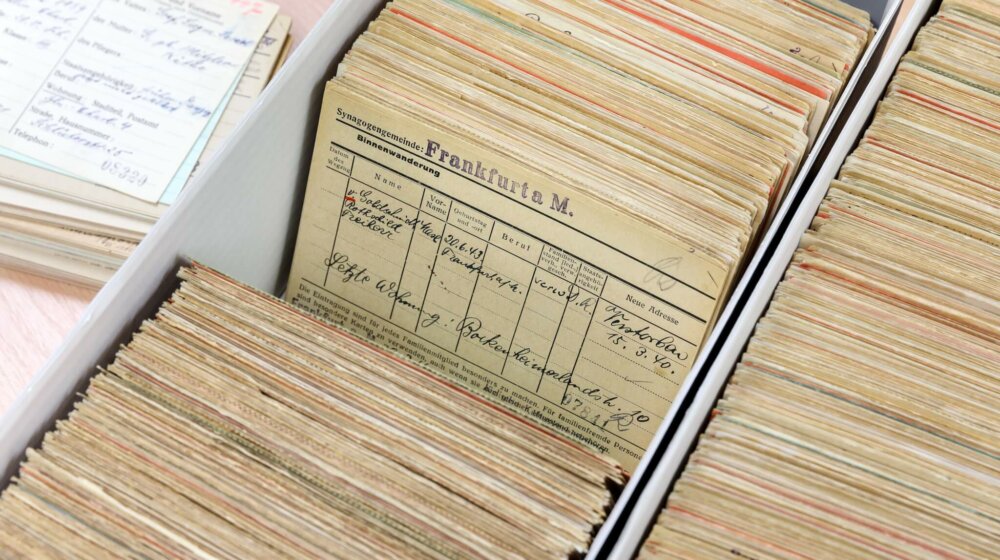

However right and important the focus on digitization and online access is, our work is based on documents made of paper. And those documents are what constitute the value and authenticity of the Arolsen Archives. Yet it does not suffice to preserve the originals; we also have to do everything in our power to prevent their deterioration. In 2018, we once again succeeded in raising special funds for that purpose. We also have a new damage register that helps us set sensible priorities in the selection of documents for restoration. As an archive, we naturally have to give our holdings optimum protection from unexpected events. One building block in that effort is a series of emergency workshops we’ve been carrying out successfully.

Preservation is not a passive matter but requires action: repairing the documents and protecting them from decay, keeping track of their condition, preparing for emergencies.

Using Resources

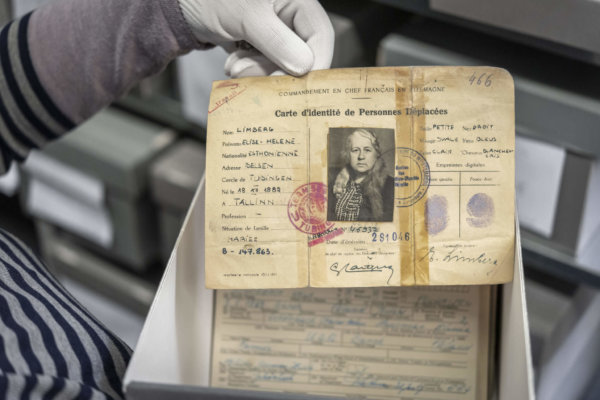

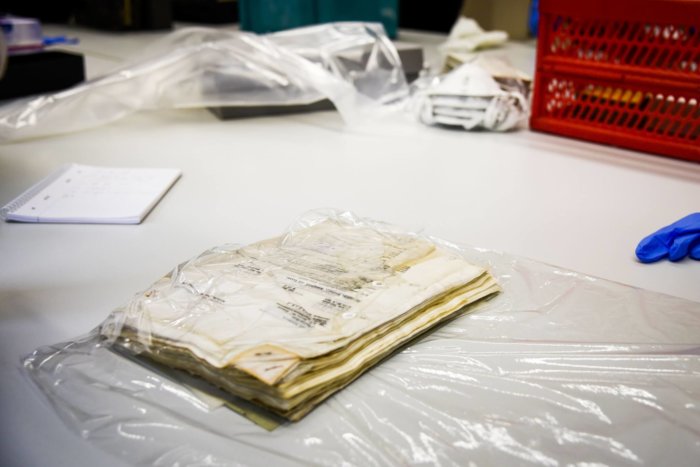

Restoration is expensive, as are preventive measures for the preservation of the holdings. Since the establishment of the special program for the Preservation of Written Cultural Heritage (Koordinierungsstelle für die Erhaltung des schriftlichen Kulturguts, KEK), the Arolsen Archives has repeatedly profited from additional funds to master this mammoth task. “We’re very glad and very grateful that the arguments we presented to justify the need for support above and beyond the usual budget were convincing”, comments Christian Groh, the head of the archive. This year once again, thanks to the German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, the Arolsen Archives was able to have an important sub-collection deacidified – the care and maintenance documents of victims of Nazi persecution from Austrian DP camps – and the most urgent repairs carried out. Now 301,000 documents are protected for the coming decades.

The care and maintenance files are kept in envelopes that have to be cut open before deacidification.

The conservators use razors to remove the photos from the so-called CM/1 files.

For the duration of the treatment, riveted photos are removed from the paper with a small striking tool.

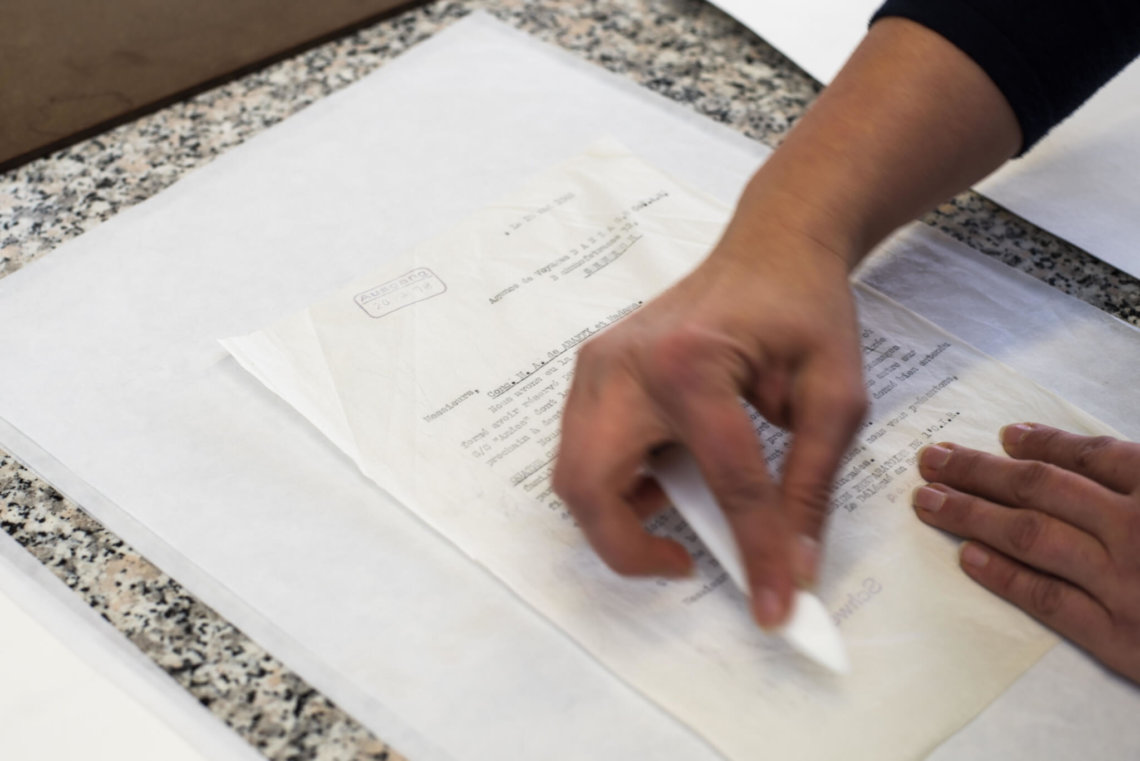

After the mass deacidification process, the conservators smooth and dry the documents.

Steeled for Emergencies

A paper monument must not only be protected against gradual processes of decay brought about by acid or inadequate packing and storage. Again and again, disasters have shown that fires, storms and water penetration can damage even well-protected holdings. To cope with this problem, the Arolsen Archives has joined with eleven other cultural institutions to form an emergency network. Mutual support in emergencies and ongoing emergency preparedness are as much a part of the emergency plan as alarm lists and facility maps with rescue priorities as well as the equipment necessary for the recovery of the collections. Each room of the archive is equipped, for example, with a set containing sponges for rough cleaning and foil for covering shelves.

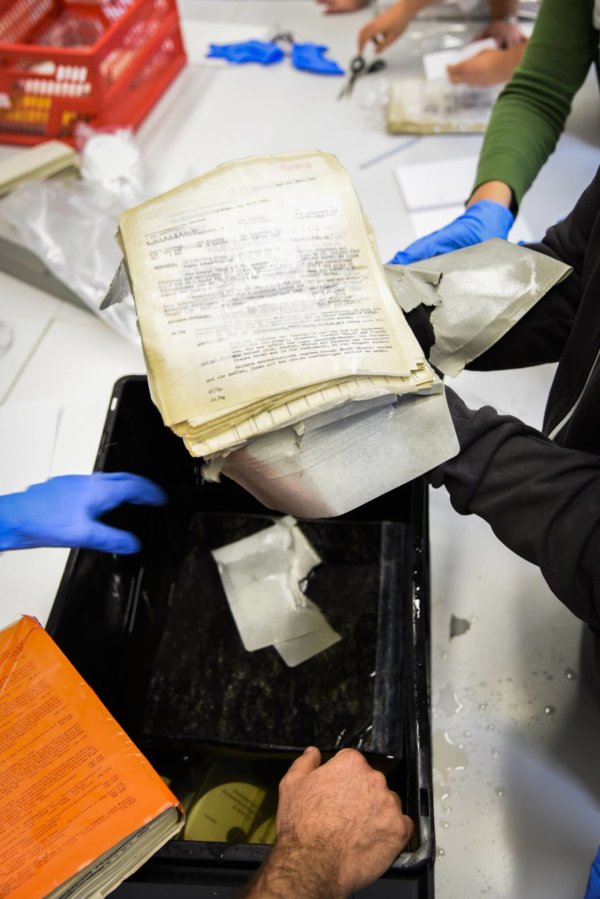

When the Water Comes

After a workshop last year on handling the emergency equipment, this year the Arolsen Archives carried out a course on the procedures to follow in case of water penetration. Several staff members from our partner institutions also took part. Under the guidance of the conservator Jana Moczarski from the University and State Library Darmstadt, more than twenty participants practiced, among other things, recovering wet paper. “It’s not at all easy to carry and pack the heavy, waterlogged paper without causing damage”, remarks Franziska Schubert, the Arolsen Archives emergency officer. “Workshops like this one are very helpful because they convey knowledge and provide an opportunity to practice, enabling us to respond all the more confidently in emergencies.” Two further workshops with other focuses are now in planning.

Wet paper is astonishingly heavy and tears easily. To carry it, it’s important to create small batches. Because mold can develop in as little as 36 to 48 hours, it’s important to perform the recovery procedure rapidly while at the same time exercising the utmost care. Everyone has to know beforehand how to respond. Workshops like this are one way of achieving that end. Wet paper is not dried with heat but frozen at a temperature of at least -20° C. Freeze-drying prevents the ink from running, the individual sheets of paper from sticking to each other, and mold from forming. The Arolsen Archives accordingly has a contract with a cold storage warehouse in the region as part of its emergency plan.