We had to change all our plans - but a lot of things still turned out extremely well. 2020 was a real challenge for all institutions involved in honoring the memory of the victims of Nazi persecution. Many commemorative events that were scheduled to take place in public spaces to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation from Nazism had to be cancelled due to the pandemic. The Arolsen Archives responded by transposing remembrance into the virtual world and building a digital memorial to the victims of persecution that anyone can contribute to.

Floriane Azoulay,

Editorial

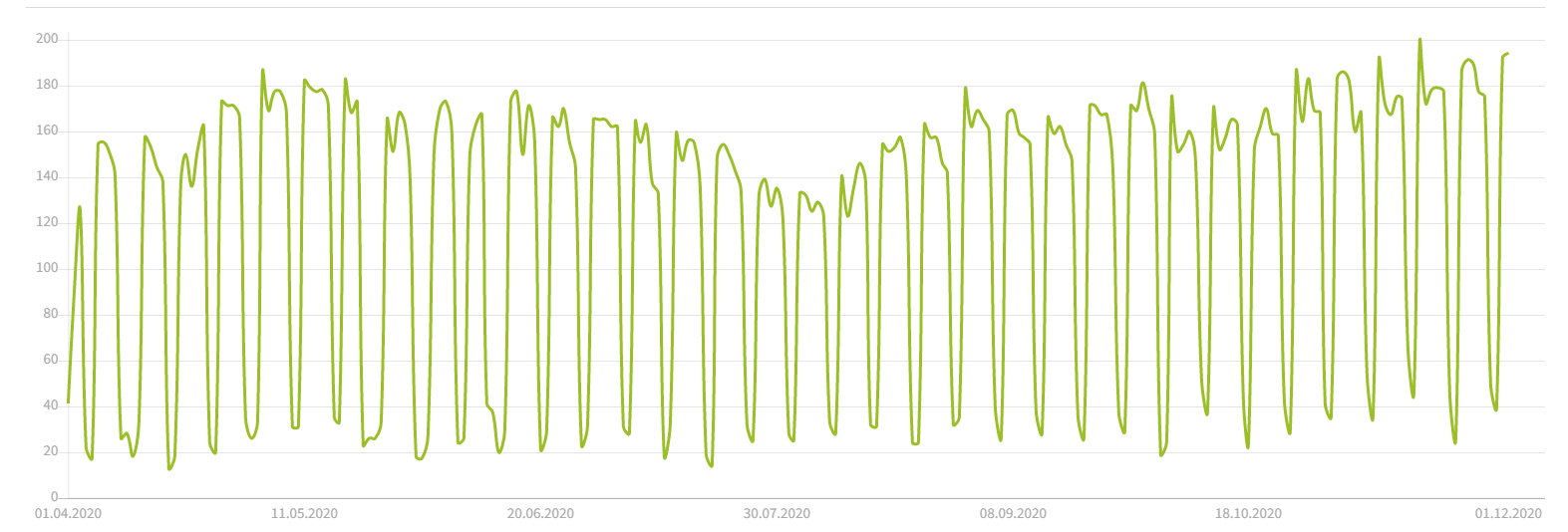

We launched #everynamecounts at the beginning of 2020 as a "small" pilot project with a number of schools in Germany. The feedback we received from participants was so positive that we began to think about expanding the initiative. The fact that a global and highly successful crowdsourcing campaign sprang from these small beginnings just a few weeks later was due in part to the outbreak of the pandemic. All of a sudden, people were stuck at home with time on their hands, and many of them were looking for something useful to do. And building a digital memorial to millions of victims of Nazi persecution is a participatory project that can only grow if a large number of people give some of their time to it.

I was deeply moved to see how quickly thousands of people from all over the world embraced #everynamecounts. A vibrant virtual community of committed individuals engaging in lively conversations with one another has emerged in the process. The fact that so many young people want to take part and are keen to find their own way of relating to stories of persecution from the Nazi era has shown us that the subject is not “ancient history.” For instance, the enthusiasm of the group of students from Florida who told us that they meet up online almost every day to work on the project together will stay with me forever.

We have improved our productivity

Digitalization played an important role at the Arolsen Archives again in 2020 – and not only in connection with #everynamecounts. The pandemic has shown just how far the organization has come in other areas too. We managed to complete the move to a 100% digital workflow almost without a hiccup. There was no drop in productivity and no delay in processing inquiries – on the contrary, by the end of the year we had managed to reduce the maximum waiting time to four months, which even exceeded our own targets. This is a real achievement on the part of our staff and something I am particularly proud of.

Of course, this difficult year has also brought significant changes for many other projects too. Our #StolenMemory traveling exhibition was supposed to tour all over Germany in 2020 to draw attention to the fates of the concentration camp prisoners whose personal effects are stored in our archive. However, we were only able to show the exhibition in a very small number of places. Most of the programs we provide for memorials and schools had to be interrupted as well. But here too, our teams were creative and used the opportunity to develop digital projects like the new #StolenMemory website and materials for distance learning.

Working with new partners to bring remembrance into the here now

Towards the end of 2020, we found a large number of new partners who are now helping us to grow #everynamecounts and make it into an even bigger global campaign. They include large international organizations like UNESCO and institutions from the worlds of education and politics that were previously unaware of the work we do. All of them reacted enthusiastically to the concept of digital remembrance and were quickly won over by how easy it is to participate.

One of the things I am especially looking forward to next year is working on the digital memorial together with these amazing partners and our own dedicated team. We have a lot of work ahead of us because we need to integrate the incredible amount of data we have collected during the course of the project so far and make it available in our online archive. Once that has been done, the information will be accessible to all, and this is essential if we are to achieve our overriding goal of bringing remembrance into the here and now. The materials in our archives tell victims’ stories, and we are keen to relate their fates more closely to the situations people face today. Because racism, antisemitism, and persecution are not history, they are an everyday reality for many people all over the world.

» Every name is a pebble to make a memorial. Every name deserves a kind, sorrowful thought. «

» Each card reminds me of how fortunate we are today - we should count our lucky stars every day. We must never forget. Projects like this one are key to ensuring that goal is met. «

» As I go through these records I remind myself that every number and name was once the child of loving parents and part of a community. Every name does count! «

Volunteers about #everynamecounts

Arolsen Archives and the pandemic

Pioneer in working virtually

Social distancing rules, lockdowns, and the risk of infection impacted almost every organization in 2020. But what do digital work and home offices actually mean for an institution like the Arolsen Archives? How can we access the original documents in our archive when we’re no longer on site? What do employees do when their projects are constrained or stopped altogether due to the pandemic? Deputy Director Steffen Baumheier and his colleagues explain how the institution adjusted to work during COVID.

“At the start of March, I called the head of our Central Services department on my way back from vacation to talk about the COVID-19 situation and how we would handle it,” says Steffen Baumheier. “When we hung up, I jokingly said, ‘See you in the fall.’ Who would have thought that it would come true in the end?” Most Arolsen Archives employees started working from home on March 9. Our permanent exhibition and library were closed, and all visits to the archive were canceled.

More flexibility working from home

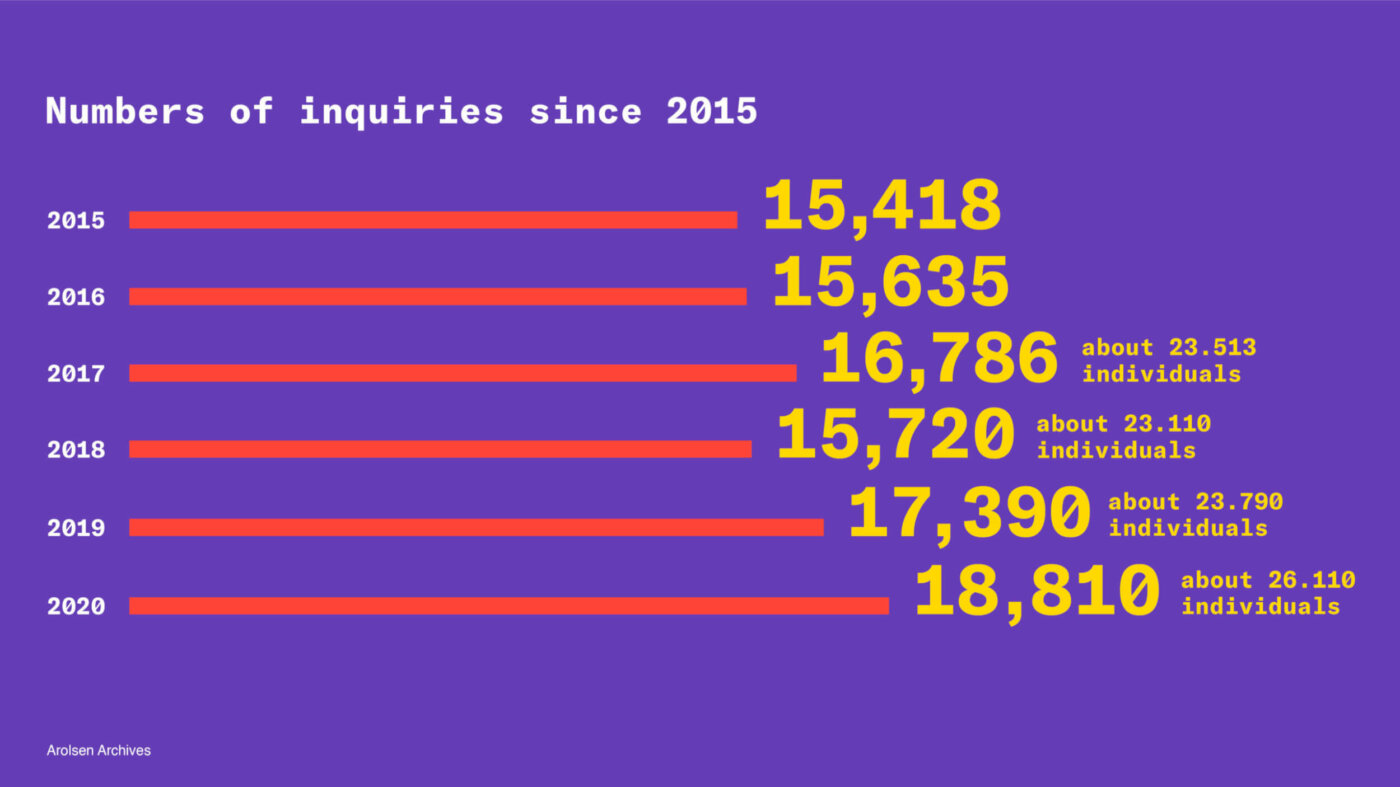

Thanks to the tireless efforts of our IT department, nearly all employees were able to do their jobs from home by mid March. “We wanted to create a safe working environment while ensuring flexibility at the same time, so we introduced an ‘honor system’ for working hours,” Steffen Baumheier explains. “Everyone can choose how to divide their time between work, home schooling and other tasks.” The Arolsen Archives took on a pioneering role here among public institutions and are frequently asked to share tips and tricks for working virtually. The institution’s productivity is also impressive, as can be seen in the shorter processing time for inquiries. Although the number of inquiries about the fates of individuals persecuted by the Nazis has continued to rise, they were processed 1.5 times faster this year.

Luckily, the Arolsen Archives had a digital advantage: most of the archival collections have already been digitized, and many departments had started to work almost entirely digitally even before this. As a result, there were almost no friction losses during the transition. Hiltrud Bitter, head of Human Resources, was happy that her department had introduced a digital personnel management system shortly before the pandemic. “Digital processes in this system are the key to successful human resources work – everything is more efficient and not so closely tied to a specific time and place. That has served us well during the pandemic.”

New communication culture at the Arolsen Archives

The employees are also communicating with each other almost entirely virtually. The teams meet regularly in Zoom conferences and chat groups to talk about their work – and sometimes to have lunch “together” or sign off at the end of the working day. Steffen Baumheier is actually in closer contact with his colleagues now: “I’m participating in more meetings than ever before and feel more involved. Virtual collaboration has led to a better communication culture here. I have the feeling that many employees are stating their positions more clearly and talking with each other more openly.”

The number of online meetings is not the only indication that good communication is even more important now. “The pandemic has shown us that there is a greater need for communication during a crisis. The flow of information has expanded considerably and is also much faster,” says HR head Hiltrud Bitter. This is why Stefan Burgheim, Online Manager at the Arolsen Archives, quickly decided to push ahead with the launch of a social intranet platform in March instead of waiting for several months, as had originally been planned. Employees can now use the COYO platform to chat, form virtual communities for collaboration, share documents and much more, all from their computers or smart phones. “The response was very positive right from the start. Now more than 70 percent of the employees are active on COYO every day,” Stefan Burgheim says.

Most Arolsen Archives employees use the new COYO intranet platform almost every day.

Most Arolsen Archives employees use the new COYO intranet platform almost every day.

Indexing documents from home

The #everynamecounts crowdsourcing initiative, which was launched as a pilot project with 1,000 students in January 2020, proved to be a real “stroke of luck” during the pandemic. In March, this campaign was opened to all employees who were temporarily or permanently unable to carry out their regular work from home. This particularly applied to the archive technology and digitization teams, who need to use the technology on site to scan, process, and digitize original documents.

Instead, they used the Zooniverse crowdsourcing platform to index tens of thousands of documents (which involves tagging them with important keywords such as names, dates and places). This paved the way for the international expansion of the campaign in April 2020. Incidentally, Arolsen Archives employees can still access original documents when necessary, since the archive technology team set up a standby service for preparing high-resolution scans on site – if a document is needed to respond to an inquiry, for example.

Online events replace in-person visits

The institution had to make new arrangements for everyone who had wanted to visit the archive in person this year. The Arolsen Archives usually receive hundreds of visitors from all over the world every year, including researchers, relatives of victims of the Nazis, and journalists. But in 2020, almost no one came to Bad Arolsen. Instead we held many virtual events, such as readings, conferences, and webinars, which were very popular. They included the online conference on “Deportations in the Nazi Era” with 250 participants in November 2020. Historian Andrea Löw (Deputy Head of the Center for Holocaust Studies at the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich) talked about her experiences at the event in a video message (only in German):

Employees in the Research and Education department developed new virtual formats for using participatory educational resources such as #everynamecounts in online school lessons. Networking events with other memorials and the annual meeting of the International Commission, which oversees the work of the Arolsen Archives, also took place almost entirely online (screenshot of meeting, see title image for this article on the right).

Digital applicants

New employees were recruited purely virtually this year. The Arolsen Archives hired numerous talents and specialists in 2020, and nearly all of them found out about the institution and its job openings via social media. The job interviews were held exclusively online via Zoom. “There are a lot of advantages to digital job interviews,” Hiltrud Bitter says. “They save time, and the scheduling is more flexible. Webcams give us a good impression of an applicant’s facial expressions, gestures, body language and how they express themselves and thus an idea of their personality.”

Marina Sauerland is one of the new employees whose interview and onboarding took place entirely virtually. She joined the Arolsen Archives in May 2020 as a fundraising officer. This is Marina’s first job after earning her degree, and she has yet to meet most of her co-workers in person: “The onboarding went well anyway, and we’re moving ahead with our projects because our communication is very good. Working in the time of the coronavirus is different, but not necessarily worse.”

From Bad Arolsen to the world

Working virtually has eliminated a locational disadvantage for the Arolsen Archives. “In the future, we want to help shape public discourse on racism and antisemitism and create a new global memory culture with campaigns such as #everynamecounts. To do this, we need international specialists from the fields of academia, cultural education and event management – people who don’t necessarily want to move to the ‘middle of nowhere’ in northern Hesse,” Steffen Baumheier says. This is why the Arolsen Archives started to introduce more flexibility and new forms of work even before the pandemic. The year 2020 accelerated this process. “We’re now gearing up for operating in a different way with a lot of virtual collaboration,” the Deputy Director explains. “Even though we’ll eventually be on site more again, it’s no longer necessary to spend five days a week in Bad Arolsen. As a digital memorial, we want to offer a digital way of working. This will expand our horizons far beyond Bad Arolsen.”

Facts and Figures

Digital education

History – interactive and virtual

Digital education formats can not only help teachers and students get through the pandemic, they can also lead to more modern, open and interactive teaching in the long term. The Arolsen Archives want to support this. Katharina Menschick and Sabine Moller are responsible for our digital learning resources, and they talked to us about their experiences with the development of new content.

Why did you want to develop and implement concepts for digital education projects specifically at the Arolsen Archives?

Sabine: After years of researching and lecturing on the relationship between media and historical consciousness, I wanted to create something myself instead of just working theoretically. The Arolsen Archives are one of the very few institutions that offer an opportunity to actively develop digital education resources for history. I was particularly fascinated by the online accessibility of the archive. Additionally, one of the organization’s main tasks – responding to inquiries about the fate of people persecuted by the Nazis – overlaps with my previous research into the importance of family memories of the Nazi period. Many of the inquiries sent to the Arolsen Archives come from relatives of people who were persecuted by the Nazis. This gave me the idea of developing distance learning courses for family researchers, which is the project I submitted with my application to the Arolsen Archives.

Katharina: I submitted a podcast project for commemorating people persecuted as homosexuals. I had often used the online archive of the Arolsen Archives for research, and I knew about #everynamecounts and was very impressed by it. What’s especially important to me is the tremendous responsibility that goes along with such an accessible archive. The question of “how should we remember and what does this remembrance mean today?” is often treated purely theoretically. But it is a very practical question at the Arolsen Archives, because these millions of documents are now available online. With digital resources, we can contextualize them and initiate a discussion about what they mean today – and I think that’s very important.

Are there any suitable formats that you can use as a point of reference or develop further?

Sabine: We were able to follow up on the existing digital resources of the Arolsen Archives, such as the e-Guide and the online archive, and a number of interesting new digital programs were created during the pandemic, including the new interactive educational content on the Holocaust from the USHMM. The Arolsen Archives are also involved in projects for providing documents in interactive learning environments for students, such as the IWitness platform of the USC Shoah Foundation. But the pandemic has also revealed just how much is still lacking. Particularly when it comes to explaining history, there are very few formats that work for pure distance learning. Most require the involvement of teachers or other educators.

Katharina: We also often participate in events on the topic, and we have a network of colleagues with whom we can discuss technical questions and suitable forms of conveying content. One good example of this was the international winter school on “Nazi Forced Labor: History and Aftermath,” which we held online in 2020 in cooperation with the Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center in Berlin-Schöneweide. In a workshop we were able to talk with colleagues from all over Europe about digital methods in memorial and educational work. It became very apparent that there is a great need not only to use digital formats in historical-political education, but also to reflect on them.

How effectively can history and historical-political topics be conveyed digitally? What do you have to bear in mind?

Sabine: History is about interpreting sources and making value judgments. This content is much harder to operationalize than in mathematics or the natural sciences, for example, where you can work much more easily with multiple-choice formats. In historical-political education, it’s not just about right or wrong. Simply quizzing students on dates is outmoded. We want learners to grapple intensively with the historical sources. Our content and formats also have to be suitable for teaching digital literacy, which entails the competence to acquire knowledge with the help of digital media, but also to recognize and reflect on the mediality of the sources and how the material is conveyed.

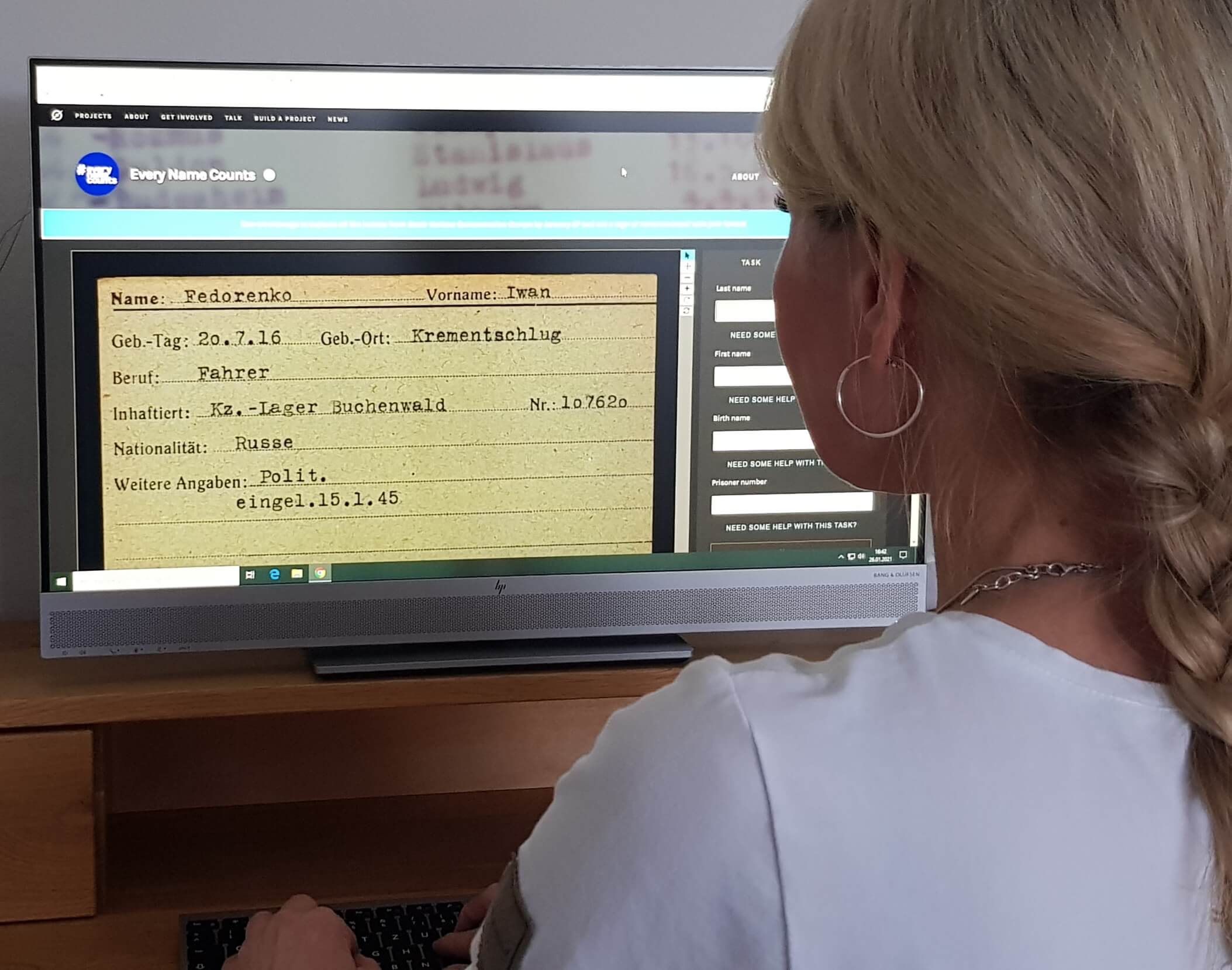

Katharina: This is precisely what we aimed for when we developed the digital introduction to #everynamecounts. It should be as easy as possible for schools to join the initiative and get important contextual information about the documents. We also published additional guidelines for teachers to help them incorporate #everynamecounts into their lessons.

How did you go about developing the introduction?

Katharina: We worked on a four-person team with Henning Borggräfe and Christian Höschler. First we chose a document that would be the focus of the introduction: the prisoner registration form from Buchenwald concentration camp for Sigfried Schneck, a Sinti boy who was deported and murdered at the age of 15. In the learning application, we show what the document tells us about his fate. We also point out that the document was created in the context of persecution and therefore reflects Nazi ideology. We devised our concept around this document and the story of Siegfried Schneck – with the requirement that the application had to provide an introduction to #everynamecounts while conveying as much information as possible about the creation and significance of the documents. Then we looked around for a technology to implement the concept. We opted for e-learning software that we can use to develop other online learning applications in the future. Sustainability is important to us, even working in the field of digital education.

How have users responded to the digital introduction?

Sabine: We’ve gotten good feedback from teachers and other educators. Many have said that, thanks to the introduction, they understand our documents better and can easily incorporate them into their teaching with #everynamecounts. The students are usually enthusiastic about the project anyway – they show a lot of interest and have many questions about it. We’re now starting an evaluation phase with them to help us better understand how the digital introduction is helping them work on #everynamecounts. We want to know what we can improve, also with an eye to future campaigns for schools.

What projects are coming up next for you? Are you going to implement the educational resources you proposed when you applied to the Arolsen Archives?

Sabine: Yes, I want to build a research tool for family researchers. It will be a long-term resource that works globally and should appeal to a wide range of people. And, of course, we’ll continue to support the educational work associated with #everynamecounts. We’ll update the digital introduction, integrate new document types, and develop distance learning courses connected to the project.

Katharina: I’m also going to continue working on the project I applied with, which focuses on remembering the queer victims of Nazi persecution. I want to develop a podcast on the topic to test the use of this medium for our educational work in general. I’d like to link the podcast with a digital resource where people can read the content and find additional information.

Katharina Menschick

studied international development and political science at the University of Vienna. She then earned a master’s degree in history and literature as a Fulbright Scholar at the City University of New York with a dissertation on digital mapping and other topics. Before Katharina joined the Arolsen Archives, she worked for the archive of the Leo Baeck Institute for the Study of German-Jewish History in New York.

Sabine Moller

Sabine Moller

studied history, philosophy and social sciences in Hanover. She earned a doctorate with a dissertation on family memories of the Nazi period in East Germany. She then conducted research into how contemporary history is appropriated and conveyed (e.g., through exhibitions, monuments and films) at the Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities in Essen, at Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg and at Stanford Graduate School of Education. After earning a post-doctoral qualification in history education at the Department of History of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and training as a UX designer, she now develops digital applications for contemporary history.