Following a pandemic-related delay – the archives were closed for some time – and with the assistance of Andreas Nikakis from the Stolpersteine initiative in Stuttgart, about 1,350 pages of documents came to light in the state archives of Ludwigsburg and Stuttgart. And in the course of my research, I came across your archive where many more documents could be found. At first, I was overwhelmed by the amount of documents. Then I printed out all the pages and started reading.

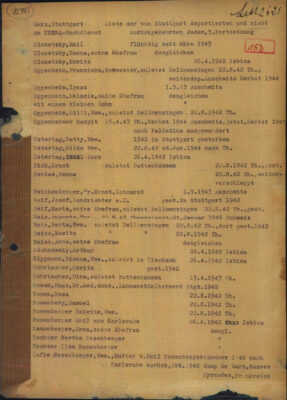

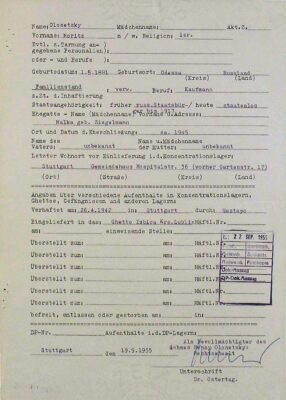

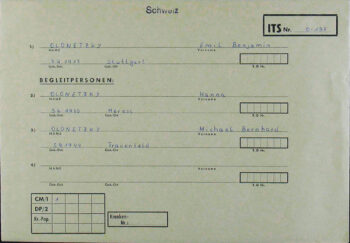

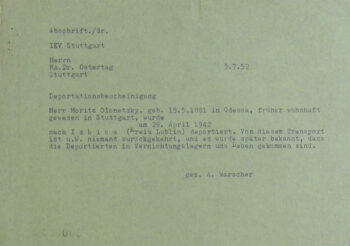

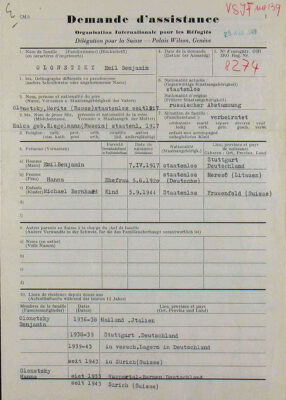

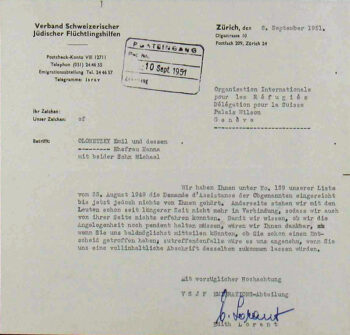

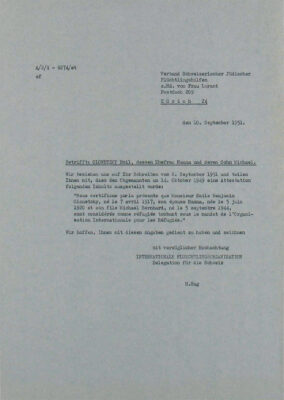

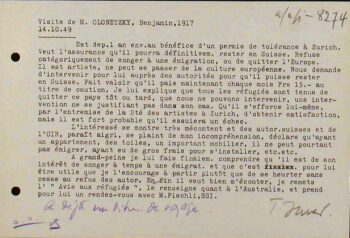

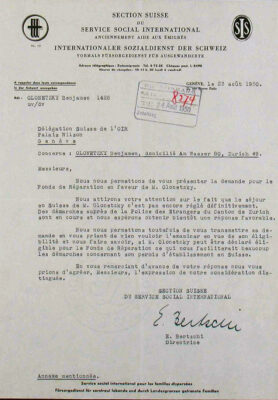

The documents include deportation lists, health insurance cards, and a lot of other materials, and essentially the correspondence my father and his siblings had with the “Landesamt für Wiedergutmachung” in Stuttgart from 1949 till the middle of the 1970s. That is to say, letters from the office and replies from the lawyers or the United Restitution Organization (URO), witness statements, etc. The burden of proof for the injustice they had suffered lay with my father and his siblings.

I found some information about my grandfather in the documents, and some about my aunts and my two uncles, but most of the data concerned my father. Although I found this surprising at first, it was quite logical really as he had stayed in Germany for almost ten years longer than his siblings, which is why he was affected more and later showed a lot of persistence in his struggle for indemnification.

“I would like to study the history of indemnification in more detail“

I received the documents in quite a chaotic state: nothing was in chronological order, there were multiple copies of some of the materials. So I tried to sort the documents. I noted down information while I was reading and copied quotations from the correspondence. I filled about 60 pages with quotations and notes. Furthermore, I read other source material such as Steffen Hänschen’s research paper on the Izbica transit ghetto (Metropol publishers, 2018) where my grandfather had been deported. The language used in the letter from the “Landesamt für die Wiedergutmachung” – the tone and the choice of words – was so shocking in some passages that I now want to study the history of indemnification in more detail.

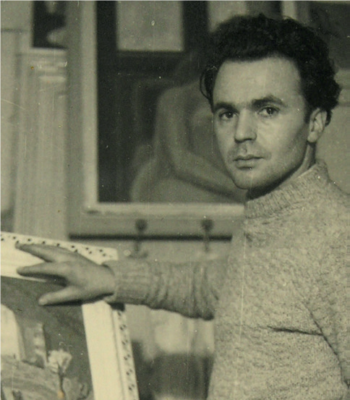

I wrote the short biographies just to have an overview at first. Only then did I have the idea to summarize them and include them in a booklet on the commemorative plaques. Meanwhile we had decided to have commemorative plaques laid not only for my grandfather Moritz, but also for my aunt Paula, my uncles Efrem and Avraham, and my father Beny.

Laying the commemorative plaques was very emotional, important, and good. The cantor of the Jewish community of Stuttgart, Nathan Goldman, sang two wonderful psalms, and the musician Frank Eisele played the accordion. I was able to talk about all my family members. It was most touching for me that people I did not know brought flowers. The ceremony somehow resembled a funeral; it is a memorial, after all. At the same time, there was something conciliatory and consolatory about it.

“You have to bow down to read the names”

At the place where my family had last lived voluntarily and where we placed the commemorative plaques, there is now a huge building which houses the Volkshochschule (a college for adults). It could have been a parking garage or a supermarket! A school – that pleases me. In fact, it is strange and sad that nothing at all is left of the world in which they lived: not a single house, not the synagogue (obviously not, as my father had to clean up as a forced laborer when the building had been reduced to ash and rubble), not a single object is left, not even a piece of furniture or a piece of jewelry.

Gunter Demnig’s commemorative plaques are valuable, solemn, simple, and discreet. If you want to read the names, you have to bow down, which I like very much. It means a lot to me that the names of my family members and their fate will not be forgotten thanks to the plaques.

People like Andreas Nikakis and all the others from the Stolpersteine initiative in Stuttgart make an invaluable contribution to preserving the memories of the victims of Nazi persecution and to ensuring we have a peaceful future. And the fact that you and the Arolsen Archives are publishing a Living History article means something similar: Individual fates tell the story of a piece of history, people are not forgotten, experiences can be shared.