A ring and its history

Thorvald Michelsen was 28 years old when the Gestapo raided his family’s home in Trondheim in October 1943 and took him away. Thorvald, his wife Gunvor and their one-year-old son Bjørn lived on the upper floor. Thorvald’s parents lived downstairs with Tore, his nephew. 77 years later, the Norwegian journalist Gøril Grov Sørdal met Tore and Thorvald’s three children in the same house.

From left to right: Thorvald’s children Toril, Rolf and Bjørn, their cousin Tore and the journalist Gøril.

Tore recounted his memory of Thorvald’s arrest. Tore himself was six years old at the time: “I was having breakfast with my grandfather when the Gestapo men ran through the house and stormed upstairs to get Uncle Thorvald.” The Gestapo also found a friend of Thorvald’s in the house, Kolbjørn Wiggen, who was also in the resistance and was hiding there. Wiggen and eight other resistance fighters were executed one month later. Thorvald and several others were deported to Germany to carry out forced labor.

He had to give up his wedding ring

Thorvald had distributed an underground newspaper for the resistance, among other things. “After the Gestapo left the house, my grandmother ran upstairs, gathered up everything that could have incriminated him, hid the papers under her clothing and left the house to get rid of them,” Tore explained.

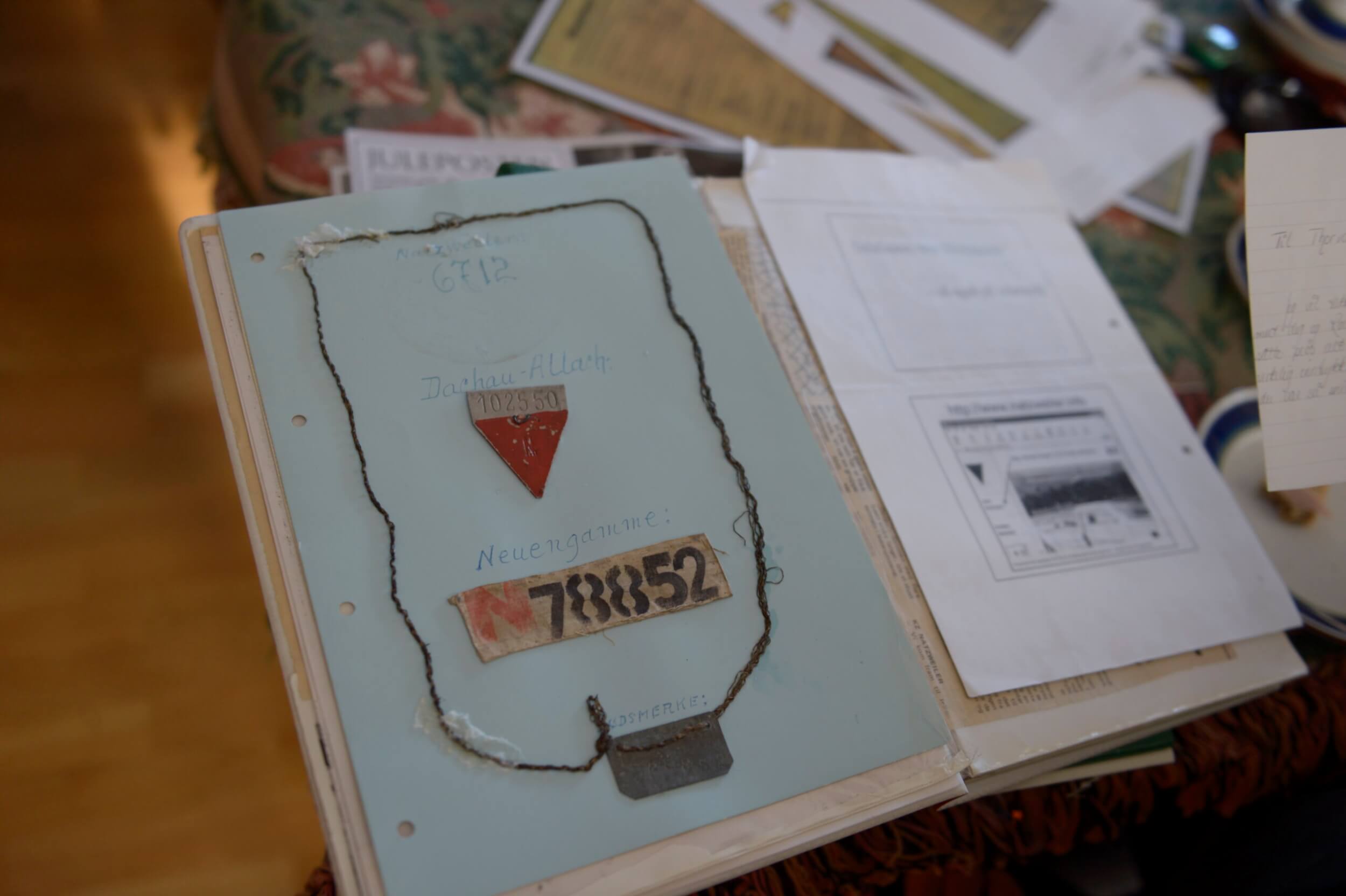

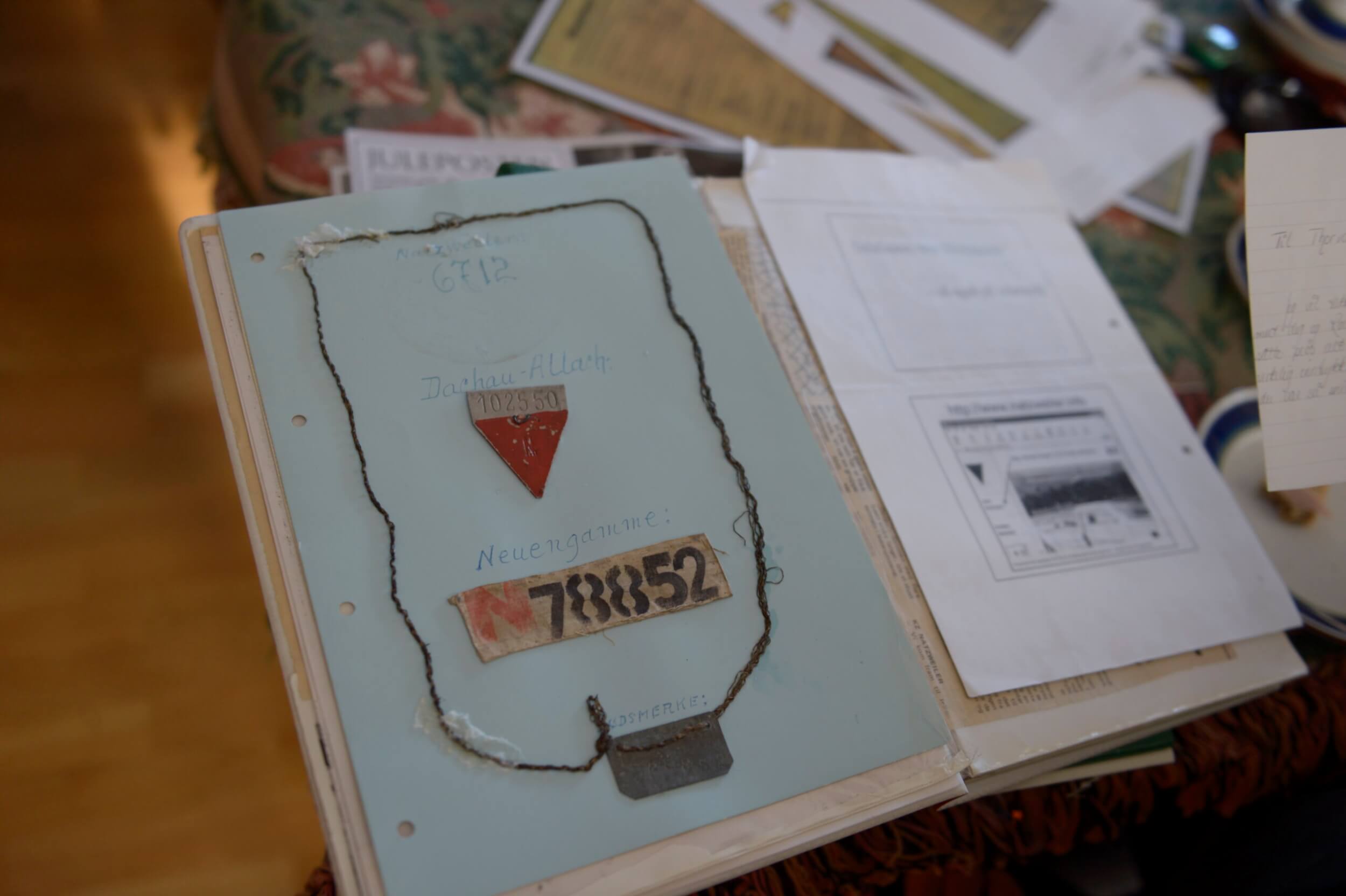

Thorvald and around 60 other Norwegians were taken to the Natzweiler concentration camp, where many Scandinavians were held. He was imprisoned there for nearly a year and had to work in a quarry. When he arrived, Thorvald had to give up his wedding ring, which had his wife’s name engraved inside. It was preserved by the Arolsen Archives until recently.

Liberated by the Red Cross

In September 1944, Thorvald was taken to the Dachau concentration camp. He was liberated there in the spring of 1945 with other Scandinavian prisoners as part of the “White Buses” rescue operation carried out by the Swedish Red Cross.

They were first taken with other prisoners from various concentration camps to an assembly camp set up especially for Danish and Norwegian citizens at the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg. From there, Thorvald was brought via Denmark to a sanatorium in Sweden, where he recuperated. On May 27, 1945, he returned home by train.

He pasted his prisoner numbers from the three concentration camps in an album to save them (photo left).

The old and the new ring

Thorvald and Gunvor continued to live in Trondheim, where Thorvald was politically active in the Norwegian Labor Party. Their daughter Toril was born a year after he returned home, and their youngest son Rolf followed in 1952. Gunvor died in 1992. Thorvald died in 2008 at the age of 93.

Thorvald had a replica of his wedding ring made after he returned from Germany. No one suspected that the original still existed.

When Gøril returned the “old new ring,” the three siblings shared many photos and memories of their parents. They also explained how they eventually found out about their father’s arrest and his experiences in the concentration camps. They didn’t learn much to begin with.

40 years passed before he told his story

“For a long time, our father almost never talked about his imprisonment in Germany,” said his oldest son, Bjørn. It was only after fellow prisoner and acquaintance Trygve Bratteli – Norway’s prime minister in the 1970s – published the bestseller Prisoner in Night and Fog in 1980 about his own time as a prisoner that Thorvald began to speak more about his experiences.

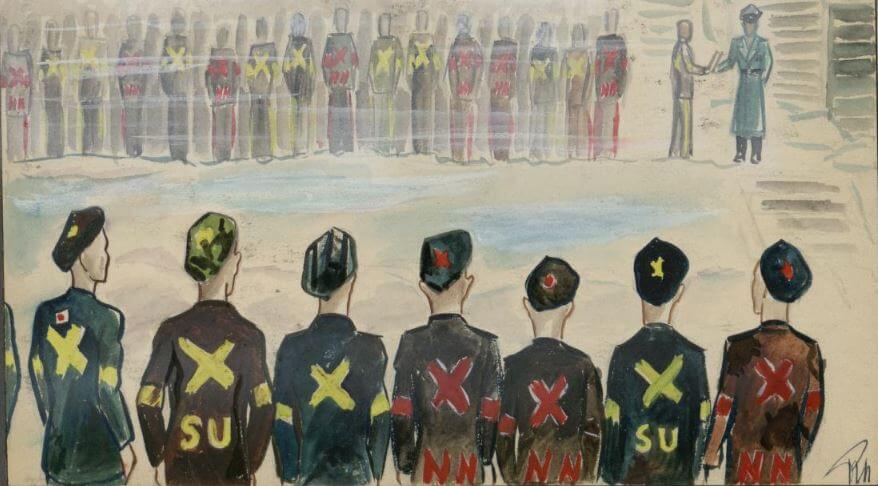

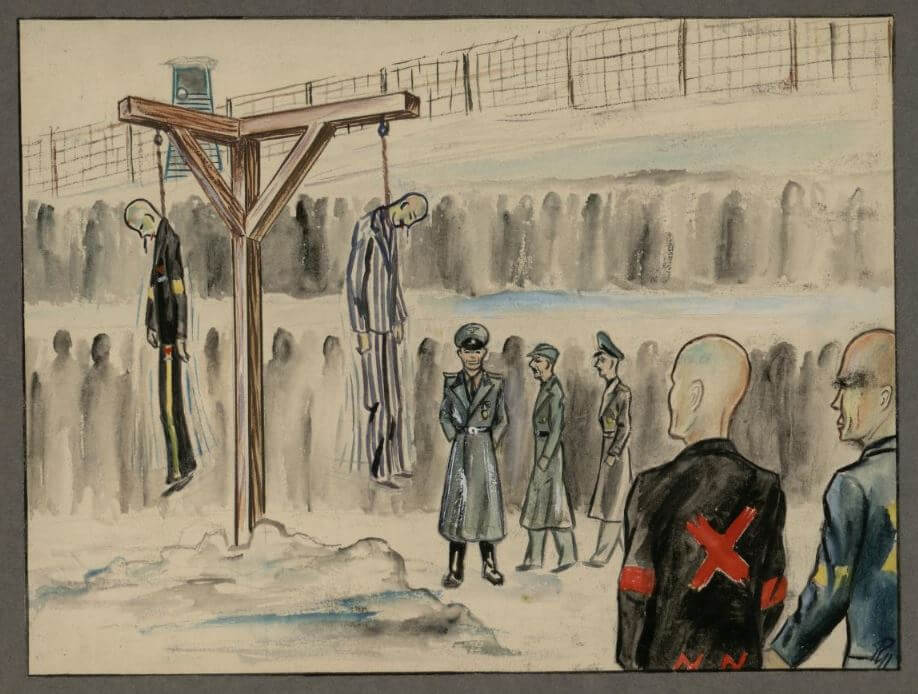

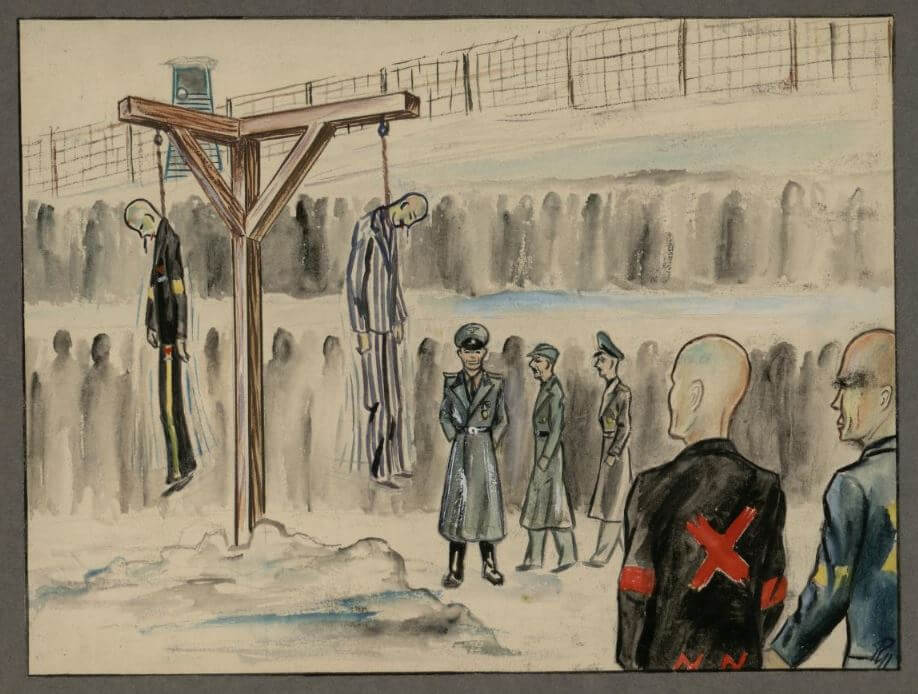

He not only told his children about what his experiences in the concentration camps meant to him, he also gave a few interviews – as did many other former prisoners from Norway around this time. In one of these interviews, he described a scene in Natzweiler that Norwegian illustrator Rudolf Næss, a fellow prisoner, had also captured in a striking drawing:

“On December 26th, two prisoners disappeared on the way back from the quarry. They were quickly found, beaten and hung. The gallows were visible from everywhere in the camp, and we all had to march past the two men and look at them. They were like wax dolls, and it was hard to believe they had ever been alive.”

Thorvald was still able to remember many details. In the same interview, he explained why he now found it easier to talk about the war and what was important to him about it: “Young people have to learn what happened. Our democracy is too valuable to lose. We have to fight to preserve it.”