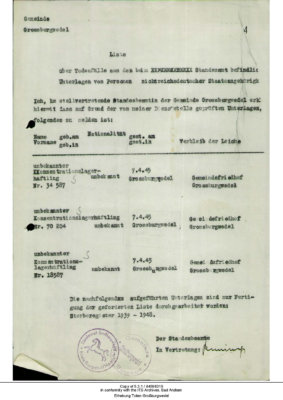

Braulia Cánovas Mulero of Spain was twenty years old when she joined the French Résistance under the code name “Monique.” The Nazis arrested her in Perpignan in 1943 and deported her to Germany, where she was imprisoned in various concentration camps. She was liberated in the Bergen-Belsen camp and on the brink of death for several weeks before she could return to France. Her wristwatch and ring remained in Germany with the personal belongings of thousands of other inmates. In December 2018, her family came to the Arolsen Archives to retrieve the two items.

Introduction

Braulia’s Daughter

Persecution History

Braulia Cánovas Mulero was born in Alhama, a town in the Murcia region of Spain, in 1920; the family later moved to Barcelona. Braulia’s father died in the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, she and her mother and three brothers fled the violence of the Franco regime by going into exile in France. After the Nazis invaded that country, Braulia – twenty years old at the time – joined the French resistance group “Alibi Morris”. There she served as a courier between Grenoble and Perpignan.

The Nazis arrested Braulia and her group in Southern France in 1943. She was kept in custody and interrogated for fifteen days, then committed to solitary confinement for a month. In January 1944 she was taken to the Compiègne internment camp and several days later transported from there to the Ravensbrück women’s camp in Germany. In June 1944, the Nazis transferred Braulia to the Hannover-Limmer subcamp to perform forced labor for tire manufacturer Continental. As the Allies drew near, the women were taken to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where Braulia was liberated on April 15, 1945. She had contracted typhus, weighed only 84 pounds and hovered on the brink of death for more than three weeks. She survived and returned to France.

Women’s Labor in the Concentration Camp

-

Female inmates loading dump cars in the concentration camp Ravensbrück, ca. 1941 ©Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück

Female inmates loading dump cars in the concentration camp Ravensbrück, ca. 1941 ©Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück -

Inmates of the Ravensbrück concentration camp carrying out earthwork in preparation for the camp’s expansion, presumably 1940. ©Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück

Inmates of the Ravensbrück concentration camp carrying out earthwork in preparation for the camp’s expansion, presumably 1940. ©Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück -

Inmates after the liberation of the Hannover-Limmer labor camp. © Algoet, Historisches Museum Hannover

Inmates after the liberation of the Hannover-Limmer labor camp. © Algoet, Historisches Museum Hannover -

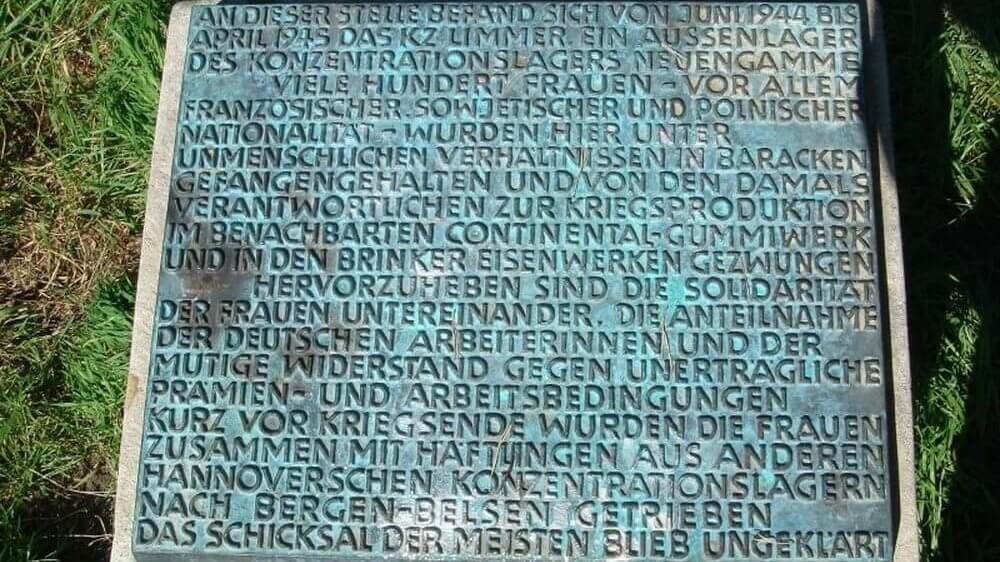

A commemorative plaque was erected in front of the Hannover-Limmer camp in 1987. © Tim Schredder

A commemorative plaque was erected in front of the Hannover-Limmer camp in 1987. © Tim Schredder -

Commemoration of the victims of the Hannover-Limmer subcamp in 1947. © Freizeit- und Bildungszentrum Weiße Rose, Hanover, reference file Gerhard Grande

Commemoration of the victims of the Hannover-Limmer subcamp in 1947. © Freizeit- und Bildungszentrum Weiße Rose, Hanover, reference file Gerhard Grande

Forced Labor

If I had had to do that work any longer, I’d have killed myself or thrown myself onto the electric fence because of the physical torment it caused me; I no longer had the strength to endure it.

Braulia Cánovas Mulero ,

“Worse than animals”

It was one of the most brutal places during the Nazi era: in 1939, the SS began building the largest women’s concentration camp in the Brandenburgian village of Ravensbrück. The first female inmates were transported there in the spring of 1939. Until 1945, more than 120,000 women were imprisoned in the concentration camp Ravensbrück. They were persecuted as Communists, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Romany and others. Many of the women were executed in the camp. To this day, it has not been possible to determine their exact number.

Braulia Cánovas Mulero came to the concentration camp Ravensbrück from the French Compiègne-Royallieu internment camp in late January 1944, in a large transport of nearly 1,000 women crowded into cattle cars. “They stuffed us in more than 60 to a car, sometimes 70 and 80…. We travelled for three days in those cars, we lost consciousness, worse than animals.” That is how Braulia later remembered the transport[1] as the beginning of her ordeal of imprisonment and forced labor.

When they arrived in Ravensbrück, the camp SS went about their usual procedure for robbing the inmates of all dignity and individuality: the women had to undress and shower in front of the guards and have their bodies shaved; then they were given inmates’ clothing and numbers. Braulia later recalled how shocked she was at the sight of her friends who finished before her – and the paradoxical fears it triggered in her:

“Because their hair had been cut off, I didn’t recognize them; when I saw them that way, without hair and completely naked …, a feeling of sympathy awakened in me, a feeling of horror and – why shouldn’t I say it – a feeling of vanity. I thought: ‘Do I have to see myself that way as a 23-year-old? It’s horrible; it’s the absolute negation of our selves.’ And I withdrew so far into myself, into my negation, that the fear of having my hair cut off was stronger than the fear of all the physical and mental suffering that awaited me.” *

By 1944, the Ravensbrück camp had long also served as a forced labor camp, where the war production effort was to be redoubled under brutal working conditions. The grounds encompassed sewing and weaving workshops. Adjacent to the camp, the Siemens & Halske company had built factory halls for the production of telephones and radios. Up to 2,000 women worked there. After months spent in quarantine and weakened by illness, Braulia had to carry out heavy physical labor in a sand pit: “If I had had to do that work any longer, I’d have killed myself or thrown myself onto the electric fence because of the physical torment it caused me; I no longer had the strength to endure it.”

In June 1944, Braulia was transferred to the Hanover-Hannover-Limmer subcamp, again to perform forced labor. In the winter of 1943/44, the Nazis had set about establishing a dense network of more than 1,000 sub- and satellite camps around their main camps. These facilities were usually built adjacent to state- and privately owned production plants of strategic importance. Hannover-Limmer was a camp solely for women at the Continental rubber works. There the inmates were employed in the production of gas masks. The inmates’ barracks had actually been designed for 500 persons, but after the arrival of Braulia’s transport they accommodated more than 1,000 women.

In Hannover-Limmer, Braulia was once again subject to the arbitrary harassments of camp imprisonment. There were countless rules, in part contradictory and almost impossible to follow. For example, the inmates were to see to it that their shoes didn’t get dirty. They were under threat of draconian punishment if they broke a rule. There were also the dreaded roll calls that went on for hours, a kind of collective punishment. “We spent January 1 standing in the snow in front of the barrack as punishment for one wrong word. I don’t know what had happened,” Braulia recalled.

Despite the severe punishments, the women resisted whenever possible. In the factory they even carried out “collective sabotage”. Braulia and her fellow inmates regularly brought production to a halt. “We all put our feet on the assembly belt together, causing the fuses to blow; that meant 30 to 40 minutes standstill…. We did that as often as we had the opportunity.”*

The SS cleared the camp on April 6, 1945, sending the women on foot to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, located 70 kilometers (43 miles) away.

[*] Neus Catalá: “In Ravensbrück ging meine Jugend zu Ende”: Vierzehn spanische Frauen berichten über ihre Deportation in deutsche Konzentrationslager (Berlin: Verlag Walter Frey, 1994). Also exists in French and Spanish.

Death March and Death Camp

xx

The Nazis referred to their final great crime euphemistically as “evacuation.” As the Allies approached at the end of the war, the SS cleared the concentration and extermination camps and sent the inmates off on foot (or sometimes by train or ship) on marches lasting several days. Anyone who couldn’t keep pace was murdered. In 1945, there were still more than 700,000 registered concentration camp inmates. An estimated one third of them perished on these journeys. The inmates themselves accordingly referred to the camp clearances more accurately as “death marches.” With these marches, the Nazis were pursuing two aims: they wanted to prevent witness statements and deprive the Allies of evidence of the crimes that had happened in the camps. And they were trying, at least in part, to preserve manpower for other camps. The destination initially designated for Braulia and other women from Hannover-Limmer, for example, was the Neuengamme parent camp, located some 160 kilometers (100 miles) away. The inmates from all five Hanover subcamps, around 4,500 persons in all, were forced to set off for Neuengamme in a frantic rush on the morning of April 6, 1945: men and women in a great procession, many without shoes, almost all of them without food or drink. Braulia’s fellow prisoner Stéphanie Kuder, a Frenchwoman, later recalled: “We walk with the men. They’re more exhausted than we are, because they’ve covered in twenty-four hours the distance that took us two days. Their faces are yellow, their skin dry, their gazes feverish…. Every few seconds, an exhausted and desperate creature leaves the procession and lies down on the roadside.” Stéphanie watched as “every 500 meters” enfeebled inmates disappeared into the forest with SS men and were shot to death there. After three days and 70 kilometers, shortly before marching past the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the women were informed that this camp had been chosen as their new destination. Starting in December 1944, more than 100 transports and death marches comprising at least 85,000 men, women and children ended in Bergen-Belsen, leading to the camp’s severe overcrowding. Braulia later remembered “a mountain of rotting corpses” upon her arrival, and “the chaos that prevailed in this women’s and men’s camp. I saw men pounce on the cauldrons and die while they were eating; I witnessed that with my own eyes.” Braulia didn’t have to endure imprisonment much longer: Bergen-Belsen was liberated on April 15, a week after her arrival. She nearly succumbed to the cruel conditions there nevertheless. When the British troops arrived in Bergen-Belsen, they found some 60,000 inmates in the camp. Around 14,000 of them died after the liberation. Altogether, more than 52,000 persons perished in Bergen-Belsen. Epidemics raged in the camp, Braulia had contracted typhus and struggled against death for 25 days after her liberation. A Romanian soldier and her own will to survive helped her: “I didn’t want to die; I wanted to live, and I managed to hang on. I weighed 38 kilograms, but I survived.”Hotel Lutetia

After the liberation, the French government provided accommodations for returning concentration camp inmates in the former luxury hotel “Lutetia” in Paris. The German secret service had previously had its headquarters there, and many members of the Résistance had been subjected to abuse and torture in the building’s cellar.

Braulia Cánovas Mulero also stayed in the Lutetia for a time in 1945 and there regained her strength. The number of persons who resided there temporarily is estimated at 13,000. Charles de Gaulle had ruled that concentration camp survivors were to have worthy accommodations where they could stay for a few days. The hotel foyer became a place where people came to look for missing family members and friends. Photos were passed around and information passed on. For many, the search was in vain, but some were lucky – for example the singer Juliette Gréco, who was reunited with her mother and sister in the Lutetia. The two had survived the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

A plaque on Boulevard Raspail commemorates these exceptional months in the hotel’s history:

“From April to August 1945, this hotel was transformed into a reception center to receive a great part of the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps. They were lucky to have regained their liberty and their loved ones from whom they had been snatched. However, their joy cannot erase the anguish and pain of the families who waited here in vain for the thousands missing.”

The Return of the Effects

It was a big family that came to Bad Arolsen from Spain and France: Braulia’s children and grandchildren, nieces and nephews. They had learned of the existence of her possessions in the archive from Antonio Muñoz Sánchez. A historian at the University of Lisbon, Sánchez had decided to spread the word about the #StolenMemory campaign in Spain after attending a conference at the Arolsen Archives. He sent information material to the media and passed on the names of Spanish victims of Nazi persecution to other historians. The Arolsen Archives staff were not only able to return Braulia’s wristwatch and ring to the family, but also show them a number of archive documents that make it possible to reconstruct her persecution path in Germany. When Braulia’s daughter Marie-Christine Jené talked about her mother during the visit, she emphasized her positive aura: “My mother always came across as very young and very happy. No one would have thought that she had been in concentration camps. She was very lively and energetic until the end, but she only lived to be seventy-three. I wish my mother was still alive and could enjoy this moment.” The visit to Bad Arolsen was also a very special occasion for Braulia’s grandchildren: “My grandmother fought against fascism. That must never be forgotten. I’m very proud of her!”

Tribute in France and Spain

Immediately after the war, the French government awarded Braulia the distinction of Chevalier (knight) of the Legion of Honor as a token of gratitude for her “struggle for freedom and against fascism.” In 1988, she was distinguished with the Officer’s cross of the French Legion of Honor. Few Spaniards have ever been granted that accolade.

In Spain, the reappraisal of the Civil War (1936-1939) and the Franco dictatorship (1936–1975) is still in its infancy. The Nazi persecution of several thousands of Spanish emigrants was largely disregarded till recently. It was only in 2019 that the Spanish government declared May 5 the official day of remembrance of the so-called "Red Spaniards" who were persecuted by the Nazis for their anti-fascist sentiments. "Spanish society has long repressed this part of its history and many people know nothing about it," explains historian Antonio Muñoz Sánchez. "The fact that something like a culture of remembrance has emerged in recent years has, above all, to do with 'pressure from below': Local initiatives and young activists are committed to ensuring that more than 9,000 Spanish concentration camp prisoners receive recognition. Also for the first time, we are talking about the 40,000 Spanish forced laborers."

In Braulia’s birthplace Alhama de Murcia, the young historian Victor Peñalver has campaigned for the appreciation of the victims. Following his initiative, the municipal council officially recognized beginning of 2018 all of its citizens who had been imprisoned or murdered in Nazi concentration camps. In May 2018, the council dedicated a monument with small monoliths representing Braulia and four other citizens as a way of commemorating the victims of National Socialism.

The “IES Miguel Hernandez” comprehensive school in Alhama de Murcia paid special tribute to Braulia on International Women’s Day 2019: The pupils and teachers gave their “Feminist Committee” – an organization that fights for gender equality in the region – a new name: “Comité Feminista Monique Cánovas Mulero.” On that occasion, they also mounted a small exhibition about Braulia’s life and her struggle against fascism. Her daughter Marie-Christine in France was very touched by this acknowledgement and explained that it had always been important to her mother “to stick to one’s convictions and moral principles and to remember that hatred leads to violence, which prevents the building of a more just society.”