Who were the forced laborers at Sebaldushof?

During the Nazi period, ADREMA plates were probably used in most German factories associated with forced labor camps. They therefore constitute lasting, tangible evidence of Nazi tyranny, evidence still waiting to be discovered in thousands of places across the territory of the former German Reich.

Further excavations planned

Coming in at 1,000 plates, the find in the Treuenbrietzen forest is one of the biggest successes in archeological excavation in Germany. Stamped consecutive numbers on the plates found to date go up to just under 10,000. This means that at least this number of plates were produced for the workers – and many of them are doubtless still preserved at the site. “We are planning further digs in the forest in the next few years, in the area of the camp administration,” explains Thomas Kersting, who as an archeologist at the

Brandenburg State Office for the Preservation of Monuments provides technical support with the excavations.

At Sebaldushof, which was built as a paper mill in 1805, covert production of munitions began as early as the 1920s. In the 1930s, a modern munitions factory was built there, where numerous forced laborers and military internees were compelled to work from 1942 until the end of the war. They were housed in a neighboring camp that was part of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Forced laborers came from all over Europe

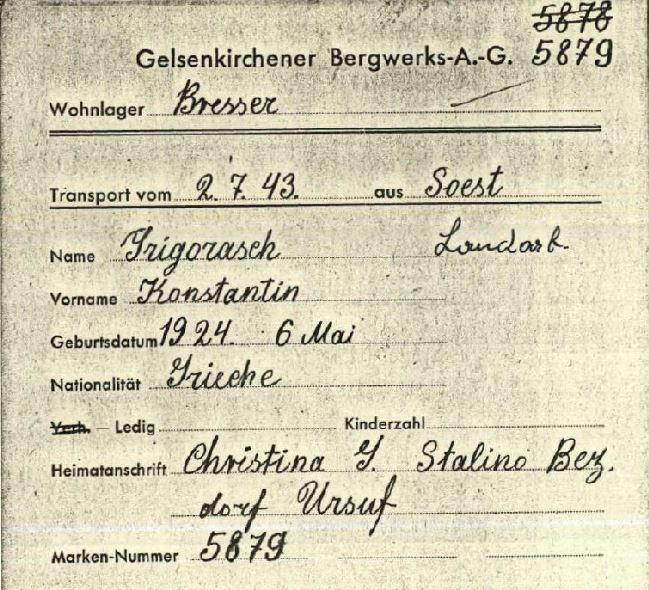

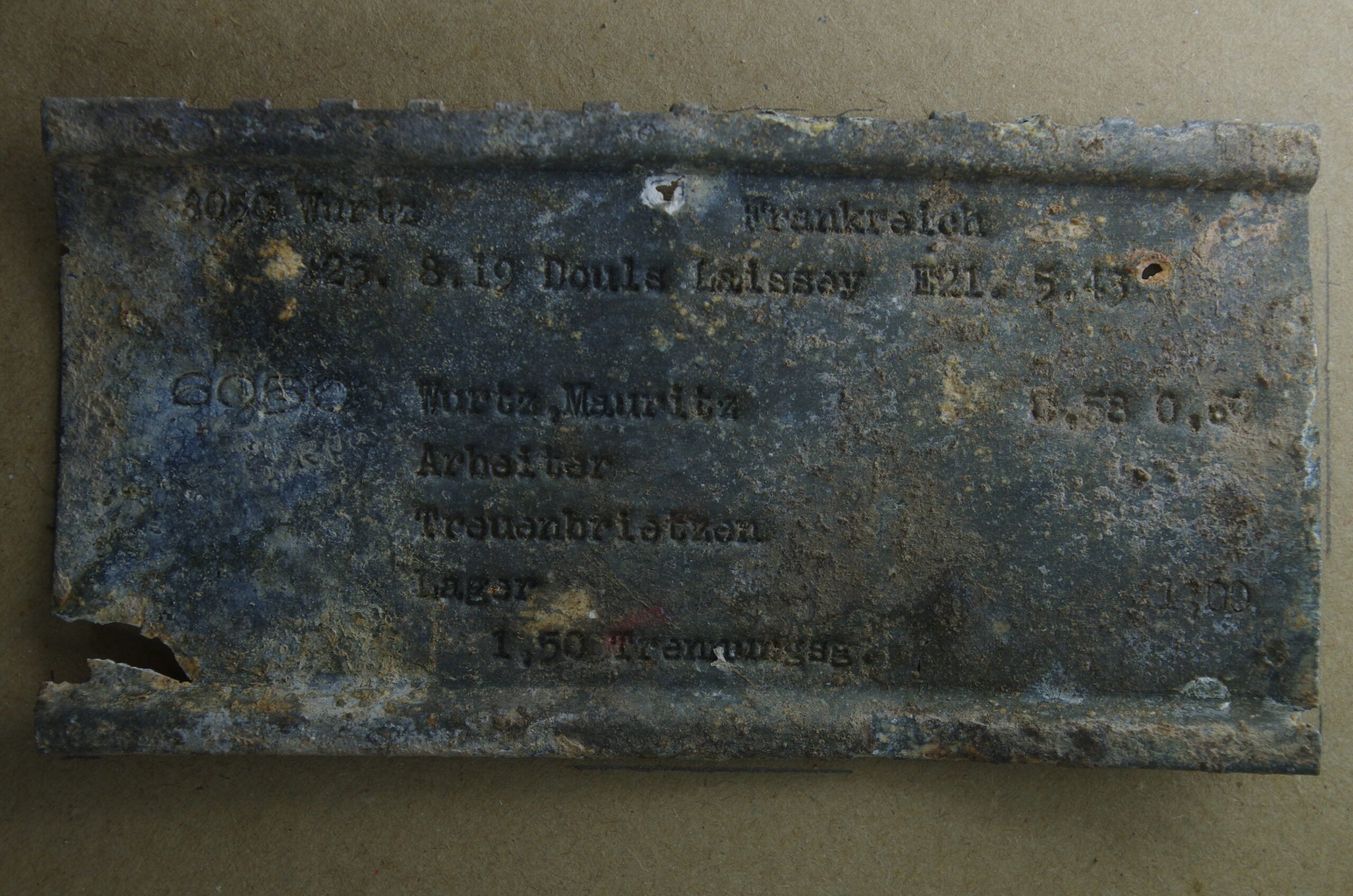

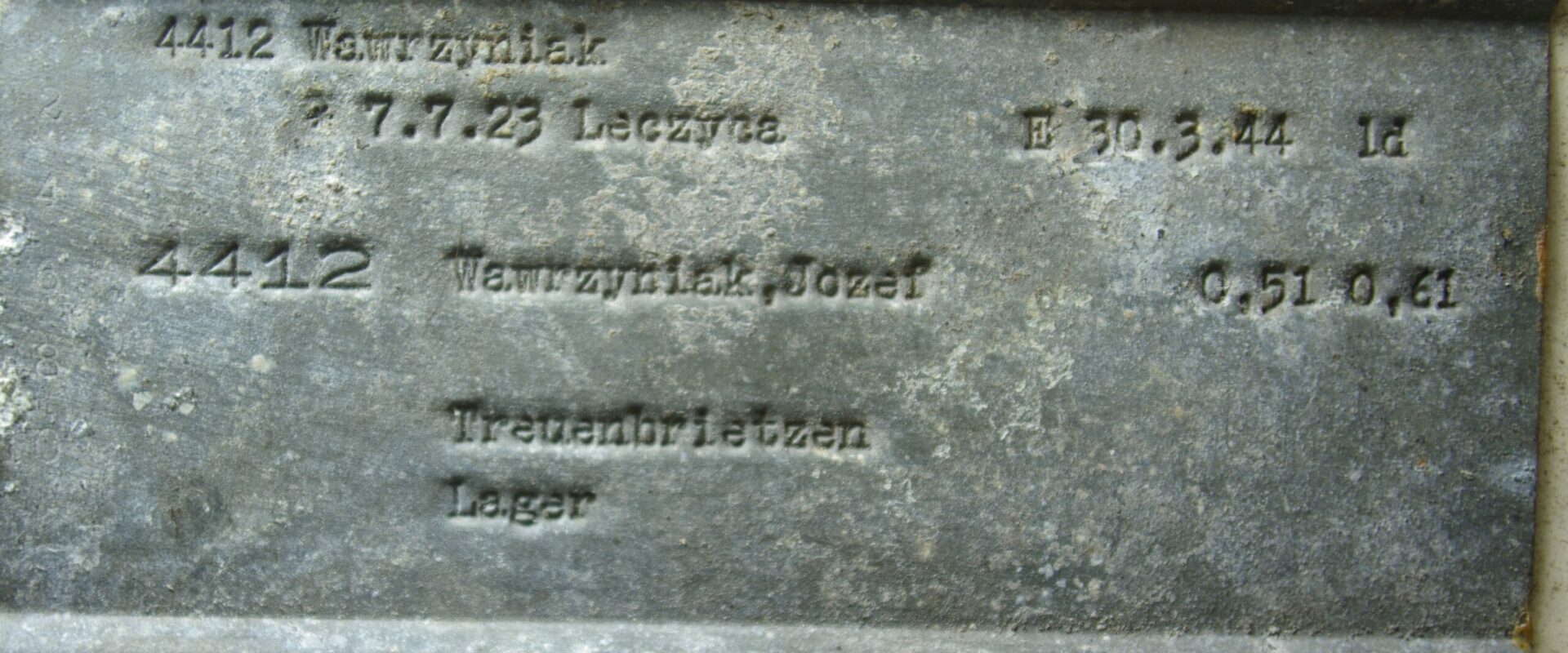

The ADREMA plates were created for all workers, including the German citizens who were employed at the factory. About half of the address plates found on the site to date pertain to forced laborers from abroad. Their home countries can often be identified from the places of origin or birth mentioned: Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Hungary, Romania, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Latvia, France, Italy, Holland, Belgium, and even Portugal. Laborers from Austria and the Sudetenland, who lived in rented accommodation in Treuenbrietzen and surrounding villages, are also recorded here, which means that they can be traced using this archeological source material.

A great deal of information on each plate

On the plates, there is a consecutive number to the left of the first and last names that provides an indication of the total number of these metal plate data carriers that may have been produced. For forced laborers from abroad, this is followed by the place where they were housed (e.g. Treuenbrietzen Sebaldushof, Treuenbrietzen camp). There is also often a job description, such as wheelwright, precision mechanic, machine worker, kitchen help. In one or two lines at the top left, the number and surname are again recorded, then the date and place of birth, and sometimes also the home country. Then there is the date of “start of work”, where the E. presumably means

Einsatz (employment), and the marital status, such as ld:

ledig (single), vh/2:

verheiratet, zwei Kinder (married, two children). On the right margin, there are what appear to be agreed wage details (possibly the hourly rate) in Reichsmarks. At the very bottom left, place names are sometimes recorded that are neither place of birth nor residence – possibly other or previous places of employment.

With the digital database, in which all information on the ADREMA plates found to date has been entered, it is now possible to draw some interesting conclusions about the group of workers at Sebaldushof. An analysis by “start of employment” shows that the first recruitments were made as early as the 1920s, and that from 1933 onwards, a few employees were added each year. 1938 to 1941 saw an upsurge, with over 40 people annually. These people were of non-German origin only in exceptional cases. From 1942 on, the big wave of deported forced laborers began: in 1943, 229 new workers were recorded, mostly people from Russia, Poland and other occupied eastern territories.

Source: Exhibition catalog “Exclusion. Archeology of the Nazi Internment Camps” (2020). Brandenburg State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and State Archeological Museum, Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center, Berlin, and publishing house be.bra verlag Medien und Verwaltungs GmbH, Berlin-Brandenburg

At Sebaldushof, which was built as a paper mill in 1805, covert production of munitions began as early as the 1920s. In the 1930s, a modern munitions factory was built there, where numerous forced laborers and military internees were compelled to work from 1942 until the end of the war. They were housed in a neighboring camp that was part of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Forced laborers came from all over Europe

The ADREMA plates were created for all workers, including the German citizens who were employed at the factory. About half of the address plates found on the site to date pertain to forced laborers from abroad. Their home countries can often be identified from the places of origin or birth mentioned: Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Hungary, Romania, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Latvia, France, Italy, Holland, Belgium, and even Portugal. Laborers from Austria and the Sudetenland, who lived in rented accommodation in Treuenbrietzen and surrounding villages, are also recorded here, which means that they can be traced using this archeological source material.

A great deal of information on each plate

On the plates, there is a consecutive number to the left of the first and last names that provides an indication of the total number of these metal plate data carriers that may have been produced. For forced laborers from abroad, this is followed by the place where they were housed (e.g. Treuenbrietzen Sebaldushof, Treuenbrietzen camp). There is also often a job description, such as wheelwright, precision mechanic, machine worker, kitchen help. In one or two lines at the top left, the number and surname are again recorded, then the date and place of birth, and sometimes also the home country. Then there is the date of “start of work”, where the E. presumably means Einsatz (employment), and the marital status, such as ld: ledig (single), vh/2: verheiratet, zwei Kinder (married, two children). On the right margin, there are what appear to be agreed wage details (possibly the hourly rate) in Reichsmarks. At the very bottom left, place names are sometimes recorded that are neither place of birth nor residence – possibly other or previous places of employment.

At Sebaldushof, which was built as a paper mill in 1805, covert production of munitions began as early as the 1920s. In the 1930s, a modern munitions factory was built there, where numerous forced laborers and military internees were compelled to work from 1942 until the end of the war. They were housed in a neighboring camp that was part of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Forced laborers came from all over Europe

The ADREMA plates were created for all workers, including the German citizens who were employed at the factory. About half of the address plates found on the site to date pertain to forced laborers from abroad. Their home countries can often be identified from the places of origin or birth mentioned: Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Hungary, Romania, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Latvia, France, Italy, Holland, Belgium, and even Portugal. Laborers from Austria and the Sudetenland, who lived in rented accommodation in Treuenbrietzen and surrounding villages, are also recorded here, which means that they can be traced using this archeological source material.

A great deal of information on each plate

On the plates, there is a consecutive number to the left of the first and last names that provides an indication of the total number of these metal plate data carriers that may have been produced. For forced laborers from abroad, this is followed by the place where they were housed (e.g. Treuenbrietzen Sebaldushof, Treuenbrietzen camp). There is also often a job description, such as wheelwright, precision mechanic, machine worker, kitchen help. In one or two lines at the top left, the number and surname are again recorded, then the date and place of birth, and sometimes also the home country. Then there is the date of “start of work”, where the E. presumably means Einsatz (employment), and the marital status, such as ld: ledig (single), vh/2: verheiratet, zwei Kinder (married, two children). On the right margin, there are what appear to be agreed wage details (possibly the hourly rate) in Reichsmarks. At the very bottom left, place names are sometimes recorded that are neither place of birth nor residence – possibly other or previous places of employment.

With the digital database, in which all information on the ADREMA plates found to date has been entered, it is now possible to draw some interesting conclusions about the group of workers at Sebaldushof. An analysis by “start of employment” shows that the first recruitments were made as early as the 1920s, and that from 1933 onwards, a few employees were added each year. 1938 to 1941 saw an upsurge, with over 40 people annually. These people were of non-German origin only in exceptional cases. From 1942 on, the big wave of deported forced laborers began: in 1943, 229 new workers were recorded, mostly people from Russia, Poland and other occupied eastern territories.

With the digital database, in which all information on the ADREMA plates found to date has been entered, it is now possible to draw some interesting conclusions about the group of workers at Sebaldushof. An analysis by “start of employment” shows that the first recruitments were made as early as the 1920s, and that from 1933 onwards, a few employees were added each year. 1938 to 1941 saw an upsurge, with over 40 people annually. These people were of non-German origin only in exceptional cases. From 1942 on, the big wave of deported forced laborers began: in 1943, 229 new workers were recorded, mostly people from Russia, Poland and other occupied eastern territories.