The terror begins

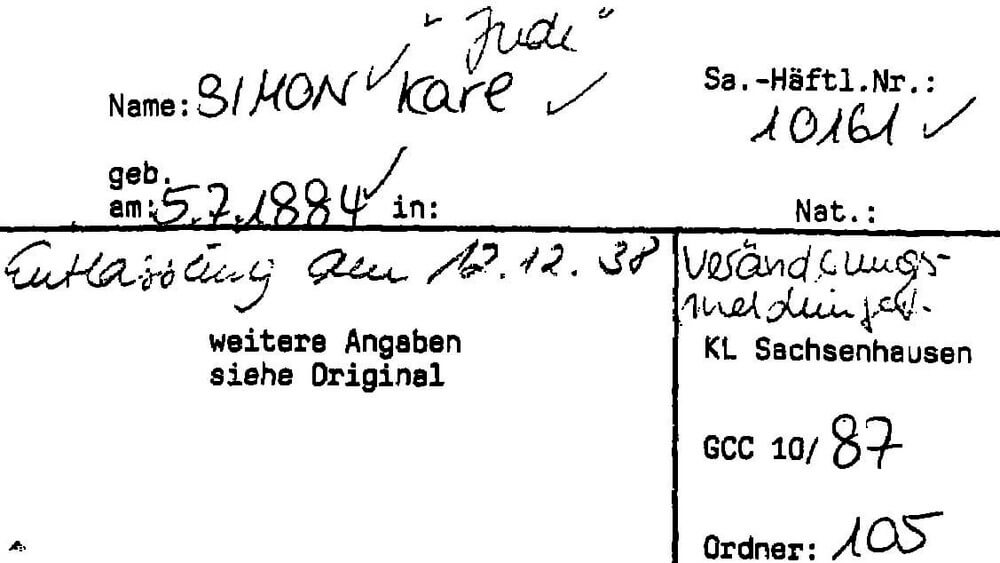

In the wake of the November pogroms of 1938, the National Socialists arrested about 30,000 Jewish men; Karl Simon was one of them. The official reason given for the arrests was “protective custody” and the “restoration of order” after all the havoc, plundering, violence, and murder. However, the real reasons were quite different: most of the Jews who were arrested were wealthy, and the intention was to force them to emigrate and for their property to be transferred to the state.

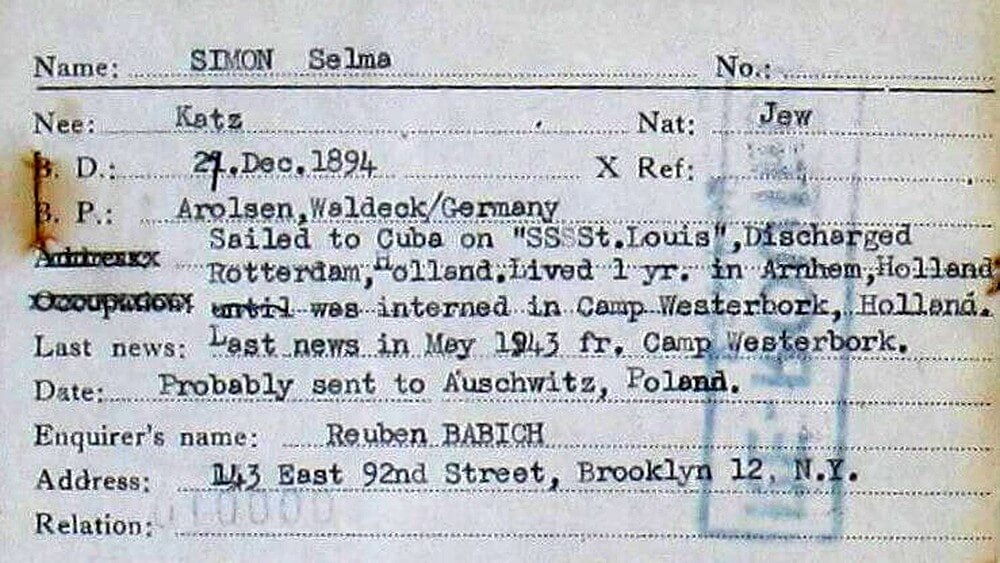

Karl Simon was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Like many other families, the Simons decided to leave Germany in order to escape Nazi persecution. Selma sent two of her daughters on a Kindertransport to England while her husband was still in custody. After Karl’s release, the rest of the family boarded the St Louis passenger ship in Hamburg. Their goal was to start a new life in Cuba and perhaps to emigrate to the USA from there. However, their journey was to take an unexpected turn. When they arrived in Cuba, they were not allowed to enter the country.

All the passengers on the St Louis were refugees. Returning to Germany was not an option for them. They had seen the consequences of radicalization for themselves and had reason to fear renewed imprisonment in a concentration camp. After an odyssey lasting days, they were allowed to disembark in Antwerp and were accepted by the governments of The Netherlands, France, Belgium, and England. The Simon family went to The Netherlands and spent the next three years in Arnhem.

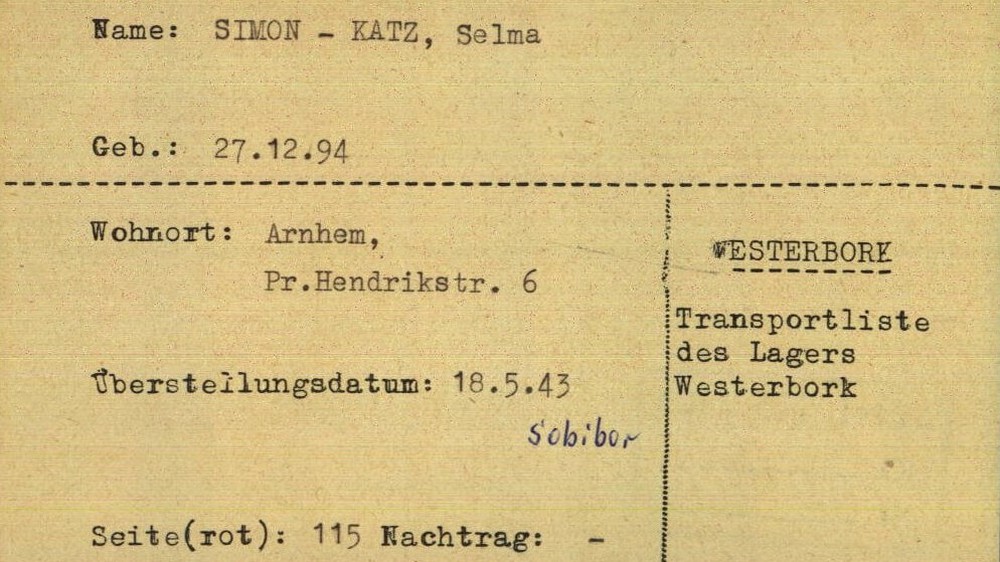

However, they were not safe from the Nazi regime there either. In 1942, Jews began to be deported from The Netherlands to German extermination camps. The former refugee camp Westerbork, now under German administration, served as a central collection point. Jews who had previously fled from Germany or Austria were interned in this transit camp. As was Selma Simon, who was detained in the camp along with her 14-year-old daughter Ilse in December 1942. According to documents from the Information Office of the Dutch Red Cross, she was imprisoned “for reasons of race.” Her husband Karl followed a few months later. Her eldest daughter Edith had managed to emigrate to England beforehand. On May 18, 1943, the National Socialists deported the Simon family to the Sobibor extermination camp in eastern Poland. They were murdered on arrival three days later.