French photographer Frédérick Carnet has released an unusual series of pictures entitled “Meine Heimat hat nur einen Namen: Frieden” (“My homeland has only one name: Peace”). The exhibition links what happened to his great-uncle Bernard Percheron, who was persecuted by the Nazis, to Frédérick’s life in his new homeland Germany – the perpetrators’ country. The documents about Bernard in the Arolsen Archives are an important part of the exhibition as they provided Frédérick with a key to his great-uncle’s experiences at the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Introduction

The exhibition

"Meine Heimat hat nur einen Namen: Frieden"

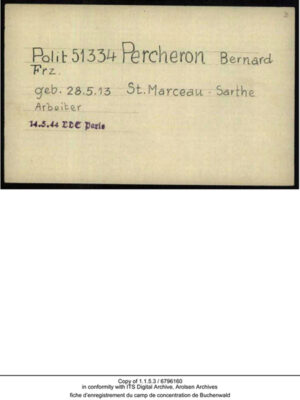

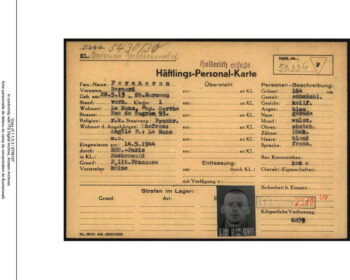

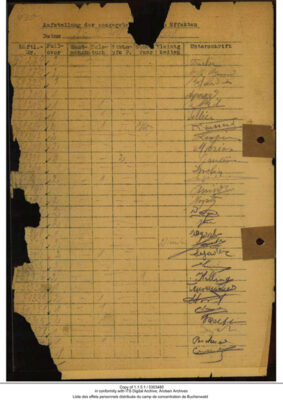

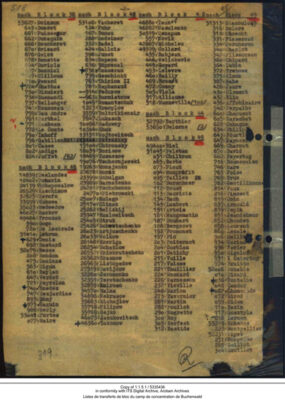

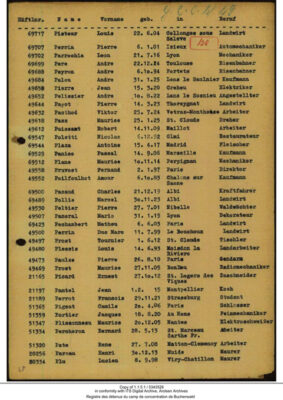

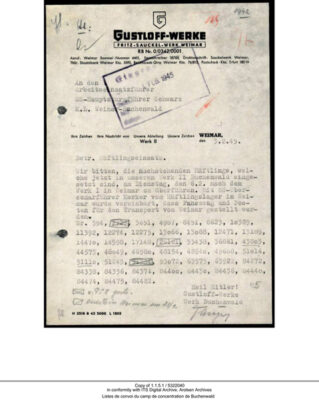

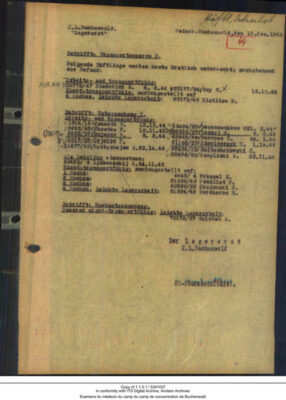

Alongside documents about great-uncle Bernard Percheron from the Arolsen Archives – such as his prisoner registration card – the series of pictures also shows photos that Frédérick took on his visits to Buchenwald concentration camp. Frédérick has combined these images and documents about what happened to his relative with photos of the place that he now calls his homeland: a community garden in Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Saxony. Frédérick lives there with his German wife Christin and their young daughter Frieda, whose photos also hold an important place in the exhibition.Interview

My picture series links the past to the present and future. And it shows an alternative to the term “homeland” used by the extreme right over recent years.”

Frédérick Carnet,

Stepping back in time

Frédérick Carnet moved from France to Saxony in April 2016 to live with his German girlfriend Christin, who he had met two years earlier during a pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago. He had already given up his former job as a commercial photographer in Paris and had entered the world of artistic photography. In Germany, he found themes and motifs for his current work: Homeland, peace, ecology, tolerance – and what happened to his great-uncle.

Frédérick, what does ‘homeland’ mean for you?

Homeland is a very German and also old-fashioned term. The expression doesn’t exist at all in French. Here in Germany, it has now been rediscovered by those who want to raise themselves up and exclude others. The AfD constantly uses the expression in its election slogans. I wondered: Why don’t the other Germans use it for themselves? Why should only the far right talk of “homeland”? That’s why I wanted to define this term for myself in the picture series. For me, my homeland is our community garden, where I find my peace. Homeland is also to do with environmental protection for me. We need to find a way to overcome pesticide-contaminated farming and grow biodynamic food. I try to do that in my garden, where I grow organic vegetables in 625 square meters of space – over 300 kilograms per year.

Frédérick in his community garden.

The German community garden is actually considered the epitome of parochialism. Do you feel welcome there?

Most people are older and tend to be conservative, of course. But I’ve met some lovely people – even though the language is always a problem as my German is very poor. My next-door garden neighbor is an Afghan family. I feel closer to them, I have to admit. Communication is more open.

Have you experienced xenophobia in Germany?

Never directly. But Christin and I saw a group of Neo-Nazis here on my very first day, and they even greeted each other with the Nazi salute. As a schoolchild in France, I heard a lot about Germany, the war, the Nazis, but it didn’t mean anything to me. Even my great-uncle’s story was of no relevance. Only once I arrived here did I concern myself more with the past – partly also because the political right had gained impetus at that time due to the refugee crisis. It annoys me that we don’t learn from the past. After all, there were also fascists in France, Italy, and Spain, who supported the Nazis. Fascism was everywhere. In the end, it was the French who took my great-uncle to the concentration camp...

How did you come across your great-uncle’s story?

When I was at school, I only knew there was someone in the family who was in a concentration camp and weighed 44 kilos when he came back. When my parents visited me here in 2017, we went to Buchenwald with Christin because we knew that Bernard was imprisoned there. It was only in that place that I understood what it was all about. The full meaning of this hell in the camp and what that must have done to my great-uncle, I only saw it there. For me, it was terrible that I hadn’t looked for so long and hadn’t had access to it. After that, I began to do research and went back to Buchenwald to take photographs.

What do the documents about your great-uncle mean to you?

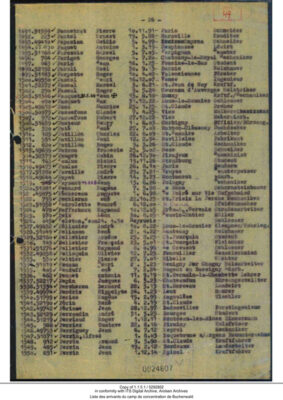

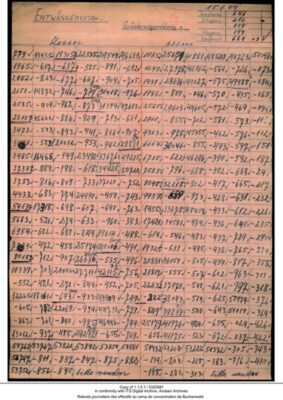

I received a huge parcel with over 70 pages of copies of documents in the post from the Arolsen Archives in response to my inquiry – that was overwhelming. These documents show that he was in Buchenwald. And what he had had to do there – some labor deployments are recorded in lists. They show the cold, bureaucratic system in which he was trapped. Thanks to the transport lists, I also know when and with whom he arrived at the camp. I am trying to link this terrible past, which I am only dealing with now, to my life in Germany today and to the future in my photo work. That’s why this exhibition is a very existential work.

And how do you see the future?

It is very closely linked to my daughter Frieda, who I am currently raising as a “househusband.” We named Frieda after “peace” (German: Frieden) to tell her: Frieda, you will be German and French, and, due to the history between these two countries, you should be called “peace.” We want to raise her as a tolerant, open person. She should also know about the past, about what happened to Bernard, and grow up with this awareness. So that history doesn’t constantly repeat itself and the same mistakes are made over and over again. Our children must find peace and an ecological balance in this world – or at least try to.

Frédérick Carnet presents further exciting online exhibitions on his website frederickcarnet.com. He is looking for suitable locations and settings, particularly in Germany, in which he can also present his work on impressions from the new homeland live. Contact Frédérick via E-Mail if you want to organize an exhibition with him.